Ships striking whales in the open ocean is a major problem, and a University of Victoria-led mission is trying to do something about it.

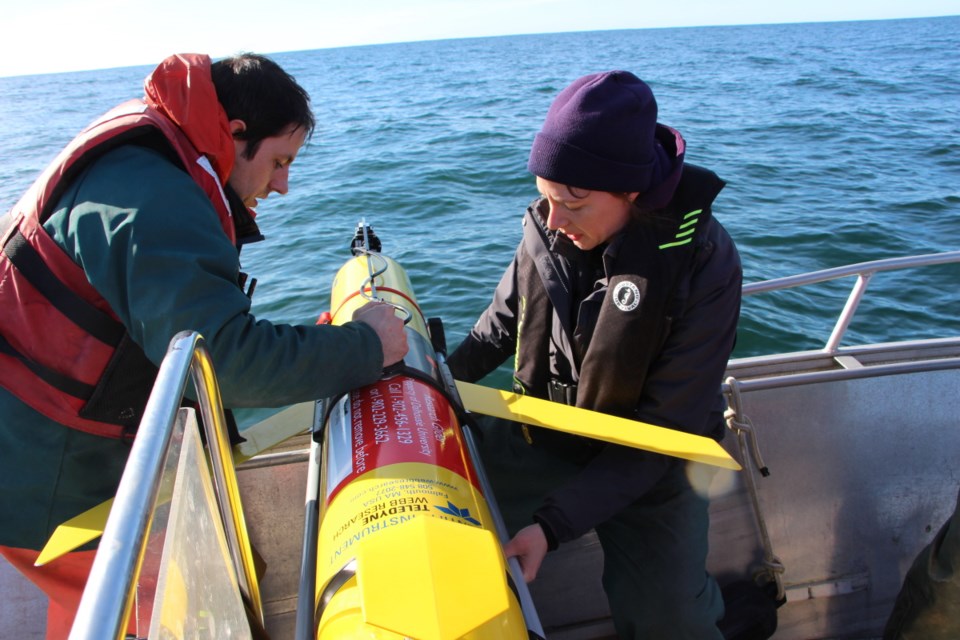

The study off Flores Island in Clayoquot Sound north of Tofino, involving a two-metre underwater ocean glider equipped with acoustic sensors, sonar and hydrophones, aims to deepen our knowledge of rare and threatened baleen whales and help protect them from being struck by ships.

Over the next three weeks, the ocean glider will allow researchers to track whale movements by listening to and recording their sounds along the shelf break — which extends about 60 kilometres off Vancouver Island to the edge of the continental shelf — in Clayoquot Canyon.

The project, led by UVic geographer David Duffus, director of UVic’s Whale Research Lab, is part of the national WHaLE project (Whales, Habitat and Listening Experiment), which investigates whale habitat and develops and implements a “whale alert” system to reduce the risk of collisions between ships and whales.

“We want to use the gliders like sentinels in shipping lanes,” Duffus said.

“It’s all in practice on the East Coast in a couple of important areas with highly endangered species. We want to do the same thing out here eventually.”

Duffus said the ocean gliders are a new technique for gaining insights into whale ecology on the West Coast, adding more information is needed on whale habitats and whale feeding “hot spots” so protective measures can be implemented.

The project is funded by the Marine Environmental Observation Prediction and Response Network based at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia. The team focuses on ecologically sensitive whale habitats on the coasts of Atlantic Canada and, now, western Vancouver Island.

Large baleen whales — such as humpback, sei, blue and the very rare North Pacific right whale — are difficult to survey, mostly due to how much time they spend underwater far from land as they feed on tiny zooplankton and/or small fish. By listening for characteristic whale noises, researchers track their movements.

Since ocean gliders can monitor at night and in poor weather conditions, researchers will have more data to map baleen whale habitat and key feeding spots.

Duffus said the glider is criss-crossing an area up to 70 kilometres off the west coast of Vancouver Island. He noted that while large whales can send out signals for up to 100 kilometres, “we’re not yet sure of our detection range and are trying to establish that.”

Duffus said the gliders — worth about $200,000 each — are used much more extensively on Canada’s East Coast, noting that when the devices rise to the surface, they send out signals to ships giving the whale’s location.

On the East Coast, whales killed by ships is a major problem, although actual numbers aren’t yet available, he said.

“On the East Coast, ship strikes are the major cause of mortality. One of the problems is that the ships are so big, they’ll strike a whale and won’t know. It’s listed in all the species at risk reports as a potential and serious hazard,” Duffus said.

“They show up on ships coming into Vancouver. The odd time you’ll see a survivor, but if it’s a big ship, surviving is hard.”