A hooded Mickey Mouse sweatshirt from Disney. Children's shorts with Wal-mart's Faded Glory label.

Clothes with hip-hop star Sean Combs' ENYCE tag.

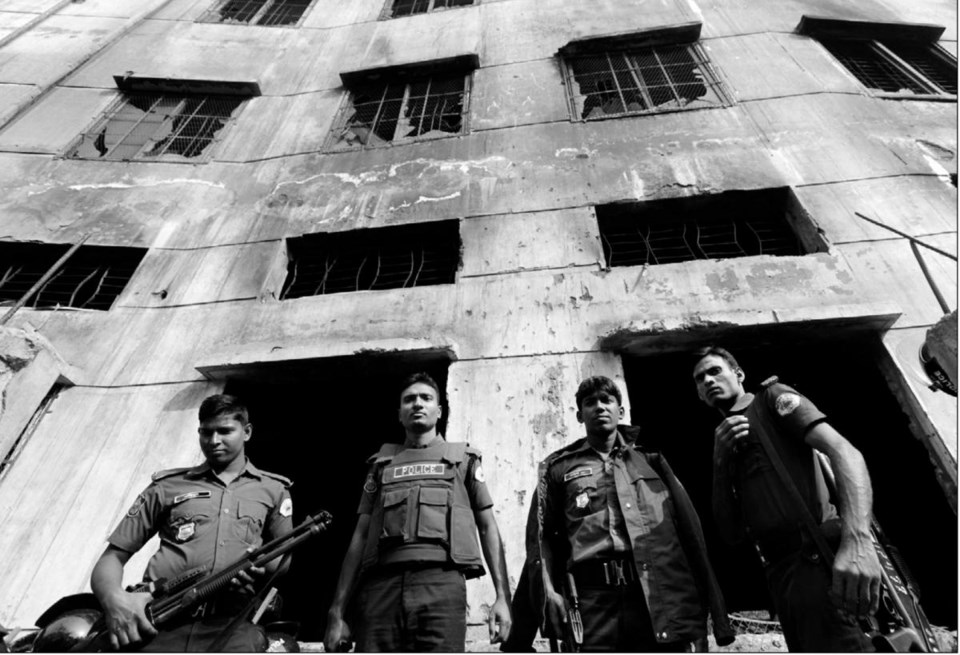

The garment factory in Bangladesh where 112 people were killed in a fire over the weekend was used by a host of major U.S. and European retailers, an Associated Press reporter discovered Wednesday from clothes and account books left amid the blackened tables and melted sewing machines at Tazreen Fashions Ltd.

Walmart had been aware of safety problems at the factory and said it had decided well before the blaze to stop doing business with it. But it said a supplier had continued to use Tazreen without authorization.

Sears, likewise, said its merchandise was being produced there without its approval through a vendor, which has since been fired.

The Walt Disney Co. said its records indicate that none of its licensees have been permitted to make Disney-brand products at the factory for at least a year.

Combs' Sean Jean Enterprises did not return calls for comment.

The tragedy at the beginning of the holiday season is putting a spotlight on dangerous workplace conditions around the world, with no clear answers to how consumers should react or who is ultimately responsible, given the way many major retailers rely on a long and complex chain of manufacturers and middlemen to keep their shelves stocked.

Labour activists have long contended that retailers in the West bear a responsibility to make sure the overseas factories that manufacture their products are safe.

They seized on the blaze - the deadliest in Bangladesh's nearly 35-year history of exporting clothing - to argue that retailers must insist on more stringent fire standards.

Charles Kernaghan, director of the Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights, said nothing will change unless clothing companies protect workers as vigorously as they do their brands.

"The labels are legally protected," he said. "But there are no similar laws to protect rights of the worker."

Bangladesh's fast-growing garment industry - second only to China's in exports - has long provided jobs and revenue for the desperately poor country, while turning out the low-priced products shoppers in the U.S. and other countries have come to enjoy.

But the industry has a ghastly safety record; more than 300 workers have died in garment-factory fires in Bangladesh since 2006.

On Wednesday, police arrested three factory officials suspected of locking in the workers who died in Saturday's blaze on the outskirts of Dhaka. Police Chief Habibur Rahman said the three will be questioned. He said the factory owner was not among those arrested.

About 1,400 people worked at the factory, about 70 per cent of them women. Survivors said exit doors were locked, and a fire official said the death toll would have been much lower if the eight-storey building had had an emergency exit. The fire broke out on the ground floor.