An undisclosed research program to reduce human-coyote conflict in Vancouver’s Stanley Park is under fire after critics say its plan to quietly trap the animals could pose a threat to public safety.

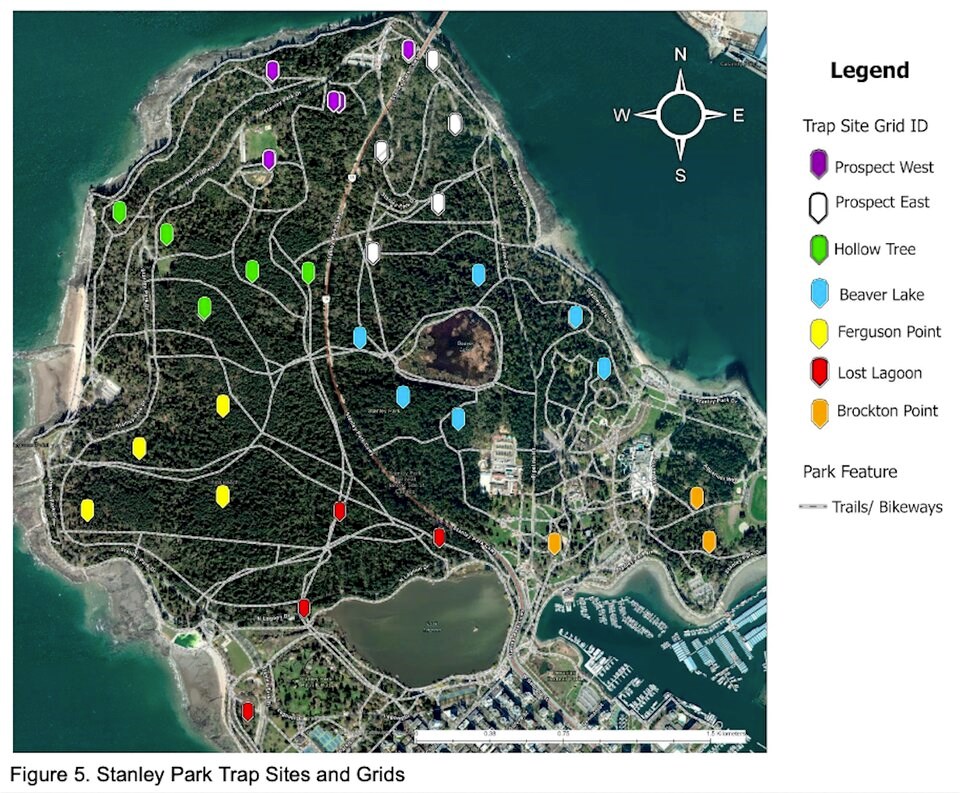

A draft of the plan, carried out by researchers at the University of British Columbia and outlined in a 38-page document seen by Glacier Media, includes trapping coyotes at 31 sites using drop nets, neck snares and leg-hold traps — the latter two fitted with a stopping mechanism that prevents choking or bleeding an animal to death.

Glacier Media has confirmed the program began “pre-baiting” some coyote trapping sites across Stanley Park last week.

Between December 2020 and August 2021, there were 45 documented coyote attacks in Stanley Park, leading to the culling of 11 coyotes.

The program, which has received conditional ethics approval from the university, will aim to reduce such incidents. Over the next four years, the plan says field research will collect population and behavioural data on the Stanley Park coyotes, including how they cross paths with humans.

The researchers will carry out “organized hazing events” to measure how they impact aggression in coyotes, among other behaviour. Those results will be compared with a parallel study carried out at Pacific Spirit Park, a large urban park dividing UBC from the city.

Aaron Hofman, director of advocacy and policy at the non-profit The Fur-Bearers, said that by failing to disclose the plan to the public, the City of Vancouver is putting workers, park-goers, pets and unhoused individuals at serious risk of injury in a park that received nearly 10 million visitors in 2022.

“I think it’s irresponsible and dangerous to allow trapping in such a public park with such high number of users,” said Hofman.

“It’s not a place people should worry about having their dog get trapped.”

Park to have 31 trapping locations

In an emailed statement, the Vancouver park board said it was “supportive” of the UBC project.

“Based on our internal review, we are satisfied that UBC has taken all required precautions and gained the necessary permits and permissions to conduct this work, including approval by the B.C. Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship,” read the statement.

The statement noted the park is closed to the public from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., and that scheduled trapping will only occur during those hours “in areas that are not easily accessible from the trail system.”

Dogs are not permitted off leash in Stanley Park at any time outside designated off-leash area. The park board added that signage will warn of active trap sites.

According to the draft plan, 31 trap sites were surveyed to ensure they are out of sight of people and heavy foot traffic, and are in a “safe area to process and release any captured animal.”

The plan warns “there will be some off-leash dogs that could get caught by one of our traps” but that “the loop can be easily removed from the paw or neck.”

Alongside the UBC research team and the Vancouver park board, the draft plan says those collaborating in the project include: the B.C. Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship; the Stanley Park Ecological Society; the Edmonton Urban Coyote Project; and the president of the BC Trapper's Association.

Public safety will be taken 'very seriously,' says researcher

Sarah Benson-Amram, UBC’s principal investigator for the program, said their research will gather data to inform ways to coexist with wildlife across Canada’s cities.

“I want to reassure those who may be concerned, the risk to people, pets and coyotes in the park is extremely low. Trapping has not yet begun,” she said in an emailed statement.

Benson-Amram said her team will “respond to triggered traps within minutes.” She confirmed UBC Animal Care Committee has conditionally approved the program, the province has issued a permit and the park board has given its approval for the work to take place within Stanley Park.

“All required licences and permits have been provided,” she said.

Hofman said the draft research plan shows no sign that it took due diligence to mitigate impacts to humans. When questioned over that absence, Benson-Amram said such approval is only required when humans are subjects of a study, and that the project is taking the potential impact on both humans and animals “very seriously.”

“The project is designed to safeguard the well-being of coyotes and park users,” she said.

Critic calls for re-evaluation of coyote trapping

Claims the project is doing enough to ensure public safety doesn’t square with past comments made by a trapper contracted to capture and cull coyotes in the park in 2021 — the same trapper who has been re-hired this time around, said Hofman.

In a draft proposal for the 2021 project, the trapper wrote to the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development that “we strongly urge the park to be closed to all but essential maintenance workers.”

Keeping the latest project out of view of the public would appear to contradict that advice, Hofman said.

Beyond the risk to humans, Hofman says laying out food and pre-baiting coyotes could create unintended consequences. By conditioning the animals to eat food, he says the plan could actually lead to an increase in human-wildlife conflicts — in a similar way that park visitors feeding coyotes led to attacks in the past.

“I think UBC should take a step back and re-evaluate this plan,” he said.

“The bigger question is Stanley Park is a public place. It’s not a lab for wildlife.”

With files from Cornelia Naylor/Burnaby Now