Greater Victoria’s water supply was assured for future generations in 2007 with a monumental deal that increased the size of the watershed by 79 per cent.

It cost about $65 million, but the Capital Regional District looked into its crystal ball and decided to pay TimberWest for 8,791 hectares around the Leech River, even though it might not be needed for almost 50 years. That goes with about 10,000 hectares of existing watershed land next door.

“There was a significant decision made by the Regional Water Supply Commission to make this purchase, much like the decision our predecessors made 100 years ago to secure Sooke Lake as the water-supply area,” said Ted Robbins, CRD integrated water services general manager.

“There’s a lot of work underway, even now, to start rehabilitating the Leech River area. Of course, it was actively logged under its private ownership.”

Another tract in the same vicinity was bought by the CRD in 2010 — 837 hectares for which $3.14 million was paid to Western Forest Products. The deal was part of a bigger arrangement that also included the acquisition of parkland.

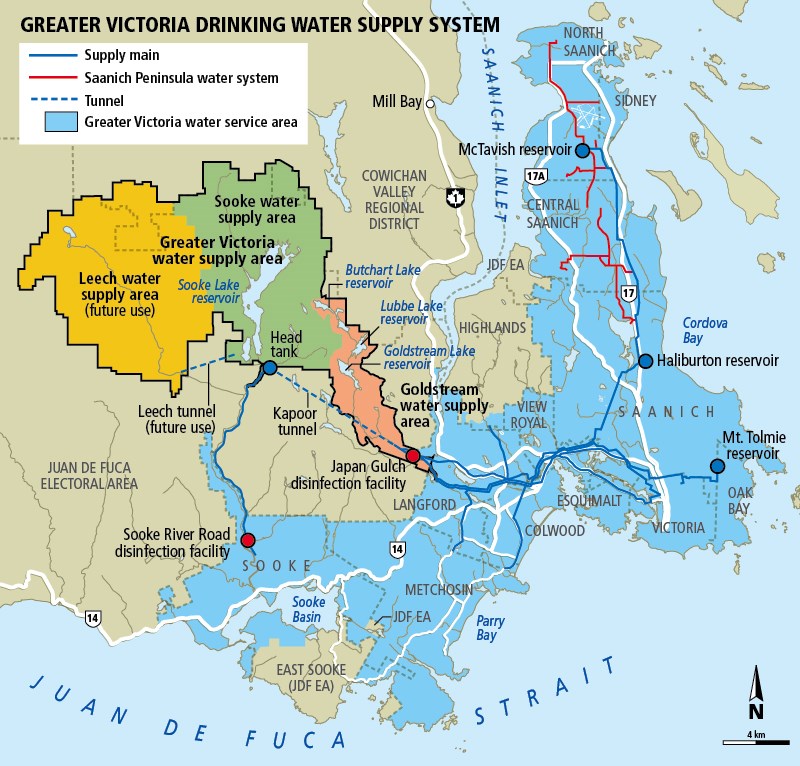

A tunnel linking the Leech River to the Sooke Lake Reservoir was built in the 1980s in anticipation of water demands, but intake and outlet facilities have yet to be put in.

Since the purchases, the biggest question about the Leech River land has been whether to close it to the public now or to wait. CRD staff recommended stopping public access in a report last fall, but the document was tabled for consideration some time this year.

Sidney Coun. Mervyn Lougher-Goodey, who chairs the Regional Water Supply Commission, said there are some “complexities” involved in the issue and it is still under review. Access to the Leech is already controlled by gates and other restrictions. As well, the only way in is through privately owned forestry land.

Since the Leech area has been 95 per cent logged and has approximately 385 kilometres of roads, there is not a lot of wilderness to preserve. The idea is to give nature a chance to regenerate the land, leading to improved quality of the water it produces.

One advantage of ending public access would be to reduce the risk of forest fires, as keeping the watershed intact means protecting the forest.

“The risk of wildfire is probably our biggest concern in the water-supply area,” Robbins said. “Should there be a fire that gets out of control, there’s the potential to cause extensive damage to the point where all the ash and sediment that would be generated would end up on Sooke Lake Reservoir.

“That would probably put us in a situation, if there was an extreme event, where we could not supply water.”

Annette Constabel, senior manager of watershed protection, said the greatest fire-prevention efforts are concentrated from April to October. Those include ground patrols, especially during the summer.

“We have aerial patrols through the summer, as well, looking for lightning strikes, that kind of thing,” Robbins said. “We look particularly up in the Leech water-supply area. In the summertime, there’s lots of recreational activities up there; people are in there camping and whatnot.”

Constabel said the last time a fire breached the watershed boundaries was a relatively minor incursion in 2006, but she said a large forest fire at Shawnigan Lake in 2012 drew close scrutiny from watershed crews.

“Every year there’s fires around us,” she said.

Summer also brings water restrictions for the public, something that draws complaints if the level of Sooke Lake stays relatively high. But Robbins pointed out that maintaining levels via restrictions helps complete an arrangement with the T’Souke First Nation to release water to the Goldstream, Sooke and Charters rivers to help fish habitat.

“By maintaining a high level in the Sooke Lake Reservoir and the Goldstream Reservoir, we’re able to provide those flows and meet our agreement.”

Lougher-Goodey added that the deeper and colder the reservoir water is, the better the quality.

Stage One water restrictions begin as a matter of policy every May 1 and run until Sept. 30. That means lawns can be watered two days a week between from 4 and 10 a.m. and 7 and 10 p.m.

Lougher-Goodey said he has an irrigation system in his yard and waters strictly within the set hours.

“I’ve got the greenest lawn on my street. You can have a very nice lawn and garden within those restrictions.”

Robbins noted that the winter of 2013-14 was a strange one for precipitation and its effect on water storage. The reservoir is often full by December, but not this past one after the driest October-December on record.

“In January, we were sitting at 75 per cent,” Robbins said. “Then we had some rain events, one in the middle of January and one in March.”

The reservoir was full for the last part of the winter and has remained at about 100 per cent into May. Capacity was increased by almost 80 per cent when the Sooke Reservoir dam was raised six metres — an expansion project that cost $23 million, including the cost of land-clearing.

A new project in the works is a $6-million to $8-million venture to replace the aging chlorine/ammonia disinfection portion of the water-supply system, located next to the ultraviolet-disinfection plant near the main watershed entrance.

“Currently, we’re operating a system which operates on chlorine gas and ammonia gas,” Robbins said. “The equipment is nearing the end of its service life.

“We’re looking at changing that process to a liquid chlorine-and-ammonia process.”

Construction could start by late this year or early next year.

• • •

Urinating in a reservoir is a stupid thing to do. A wayward teenager was in the news in April for doing just that in a reservoir in Portland, Ore., leading that city’s water bureau to dump 38 million gallons from the 50-million-gallon storage area. Rest easy — the same scenario wouldn’t happen in the Capital Regional District.

“In fact, it’s very different here,” CRD water services general manager Ted Robbins said. “There’s the potential for someone to get to Sooke Lake, because the entire area isn’t fenced, but the difference with that situation is the Sooke Lake Reservoir is raw water, so it hasn’t gone through its disinfection process yet.

In Oregon, “that was an open, treated-water reservoir.”

Raw water from Sooke Lake heads through the Kapoor Tunnel toward the Japan Gulch disinfection area.

“Japan Gulch is where all the water is disinfected and enters the supply system,” Robbins said. “It runs through a total of nine major supply mains out to the municipalities, who in turn distribute the water to the municipal customers.”

In any case, trespassing is rare, Robbins said.

“We typically don’t have many experiences with trespassing, and when we do often it’s people that don’t really know where they are. They’ve wandered in.”

Still, an unusual spate of problems with interlopers and vandals in 2012 and 2013 led the CRD to commit $364,000 last fall to a three-phase project for video equipment at key locations. That followed a break-in at a field-operations centre where such items as a generator and power saw were stolen, some attempted break-ins at other sites and vandalism of portable washrooms.

“Some teenagers made their way to the Sooke Lake Dam and that was a concern for us,” Robbins said. “We’re in the process of implementing the video surveillance.”

Others have used the watershed for their own purposes over the years, from growing marijuana to harvesting salal. But security patrols — which are present evenings and weekends, along with regular hours — work well in combination with the amount of fencing that is in place to control the boundaries, Robbins said.

Keeping the water safe and secure is also in the purview of health experts, who help set policies aimed at water quality.

“We work with Island Health to ensure that the water is safe,” Robbins said. “That includes source-water protection where we own approximately 98 per cent of the catchment lands.”

A unique aspect of Victoria’s water-supply system is that it does not use filtering, he said.

“Most large utilities have a filtration system to assist with the disinfection process.”

The CRD watershed doesn’t need it, Robbins said.

“It’s primarily focused on the fact that we control water-supply areas, so there is not a multi-use situation here. We have control over all the activities in the catchment lands, which allows for essentially high-quality raw water entering the lake.”

On top of that, there is plenty of provision for keeping tabs on what is happening throughout the collection and treatment process.

“We have literally hundreds of alarm points throughout the system related to disinfection, flow, pressure levels.”

There is even a special boom at the Sooke Lake Reservoir in the slim chance an oil spill occurs.

“If there’s a plane crash on the lake, for example, even though they’re not supposed to be flying over the lake, it would be used to capture any fuel or oil,” Robbins said.