Dr. Trevor Hancock is a retired professor and senior scholar at the University of Victoria’s School of Public Health and Social Policy.

Last week, I discussed the health impacts of climate change and ecological damage, one of three main threats to the health of children identified in A Future for the World’s Children?, the February 2020 report of a World Health Organization-UNICEF-Lancet Commission. This week, I turn to the other two threats: The health impacts of poverty and inequality, and commercial activities that harm children.

With respect to poverty, the commission states: “The evidence is clear: early investments in children’s health, education and development have benefits that compound throughout the child’s lifetime.” But they note that many children live in poverty and there is a gap between what we know children need and what they get. Closing that gap will not only be good for those children and their families, but “for their future children, and society as a whole.” Investing in children’s health, education and development is “the most powerful investments a society can make.”

So it is beyond shameful that in one of the richest countries in the world, the unanimous commitment by the House of Commons in 1989 to eliminate child poverty by the year 2000 has been utterly betrayed by successive governments. Campaign 2000, which was formed in response to that resolution, reported last month that there are “over 1.35 million children [under 18] living in poverty with their families in Canada today and income inequality, the gap between the rich and poor, has grown to unjustifiable heights.”

In 2017, the latest data available, almost one in five children (18.6 per cent) in Canada (and 19.1 per cent in B.C., or 163,730 children) lived in families with an after-tax income below the Census Family Low Income Measure. (The new Market Basket Measure used by the federal government gives a rate of nine per cent, or 622,000 children — still a lot of kids — but it underestimates poverty in a number of ways.) Campaign 2000 noted: “We have missed the opportunity to end poverty for a whole generation of children.”

But that investment has to go beyond the three areas of health, education and development to create healthy living conditions for all children. This requires policy co-ordination across many sectors, including housing and urban development, food and agriculture, energy and transportation. In the commission’s words, this requires political commitment at the highest level with “cabinet-level co-ordination across ministries.” Heads of state or prime ministers (and in our case, premiers), the commission states, “must designate a cross-cutting government ministry or equivalent to ensure joined-up action and budgeting for pro-child policies.”

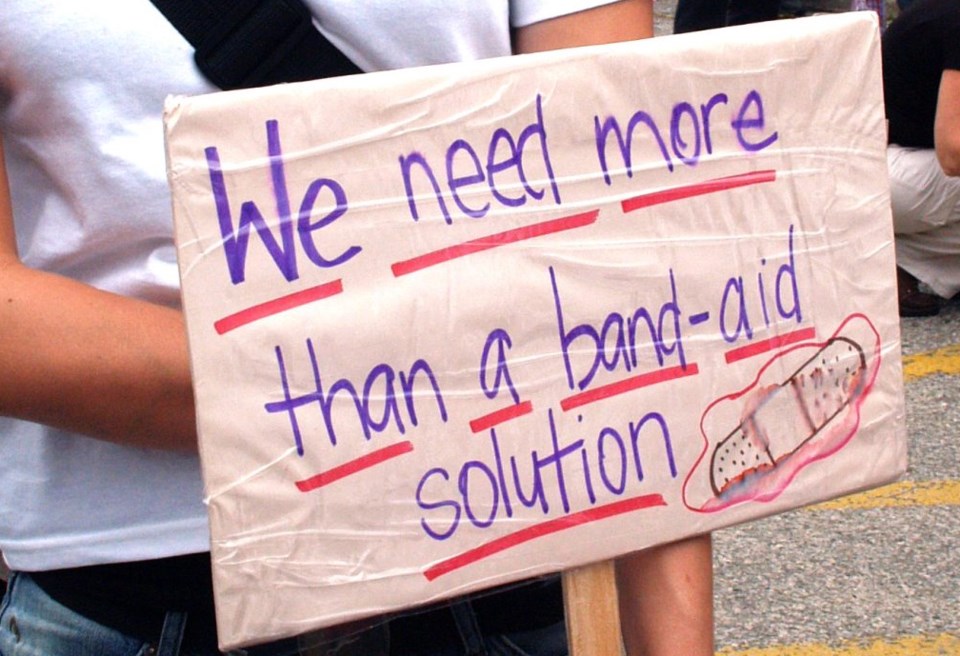

Is it too much to ask, 30 years later, that we get our act together and demand that our governments establish cabinet committees and societal roundtables and, as a first step, eliminate child poverty and then go on to create environments in which children can thrive?

With respect to commercial activities, the commission is blunt in its assessment that this “sector’s profit motive poses many threats to child health and wellbeing.” This includes not only “the environmental damage unleashed by unregulated industry,” the commission notes, but “advertising from business, whose marketing techniques exploit their developmental vulnerability and whose products can harm their health and wellbeing.” The list of industries is long, and includes fast foods, sugar-sweetened beverages, alcohol and tobacco, while the internet and social media also “exposes them to exploitation, as well as to bullying, gambling and grooming by criminals and sexual abusers.”

The commission is equally blunt in stating “industry self-regulation does not work,” calling instead for a new protocol to be added to the Convention on the Rights of the Child to protect children from marketing. Canada is a signatory to this convention, which all nations (except, astonishingly — or maybe not — the U.S.), have signed. The disgraceful failure of the Senate to pass the bill to protect children from food and beverage marketing shows why that is needed.

The commission recommends: “Governments must harness coalitions across sectors to overcome ecological and commercial pressures to ensure children receive their rights and entitlements now and a livable planet in the years to come.” There is no more important task than working to secure our children’s future, and standing up to those in the corporate and government worlds that threaten it.