A commentary by a professor of history at the University of Victoria and author of Makúk: A New History of Aboriginal White Relations.

British Columbia turns 150 years old today. Is it a time to celebrate or to mourn?

It has been two full human lifetimes since provincehood, but provinces age differently than people and British Columbia is just now coming of age.

We are finally starting to learn the stories of our conception as a country and province and, for all of us settlers, the stories are — unsettling.

Recent revelations about residential schools have caused widespread revulsion towards the attitudes the country was founded on and bring a new recognition that the province is not really even an infant compared to the traditional territories, governing bodies and stories that reach more than 10,000 years into our region’s history.

The Spaniard Juan Perez and the Briton James Cook — naval officers leading the first Europeans in what is now British Columbia — arrived in the 1770s. Europe was in the Enlightenment and the British King George III had recently acknowledged Indigenous title (1763), declaring North America could only be settled when Indigenous people agreed through treaties.

On Nootka Island off Vancouver Island, Cook met Maquinna, chief of the Mowachaht, respected and feared along the west coast where he and his warriors raided, took slaves and heads, and who had rendered all of Nootka Sound subservient to his authority. And yet, so amicable was the meeting of the sea-borne community of 182 sailors and his people at Yuquot, the Mowachaht community of about the same size, that Cook gave it a European name: Friendly Cove.

Fourteen years later, representatives of the kings of England and Spain, George Vancouver and Bodega y Quadra, and Maquinna all met as equals at his home in Tahsis. None present then could have had an inkling that their meetings would begin a century-long process leading to British Columbia’s provincehood and, with it, the theft of Mowachaht territory.

What happened since has been called a genocide and it is easy to see why. The Indigenous population of what is now British Columbia fell from around 250,000 in Cook’s time to less than 30,000 in the 1920s, mostly due to the introduction of diseases endemic in Europe and Asia but unknown in the Americas.

Cook’s crew introduced venereal disease, while the deadliest disease — smallpox — made its way up from Mexico via the trade routes that connected the Indigenous world. It was followed by measles, influenza, tuberculosis, chickenpox and smallpox, which returned to cut down each generation born since the last epidemic.

Along with the damage their diseases wrought, the British immigrants also brought King George’s promise that treaties would be signed.

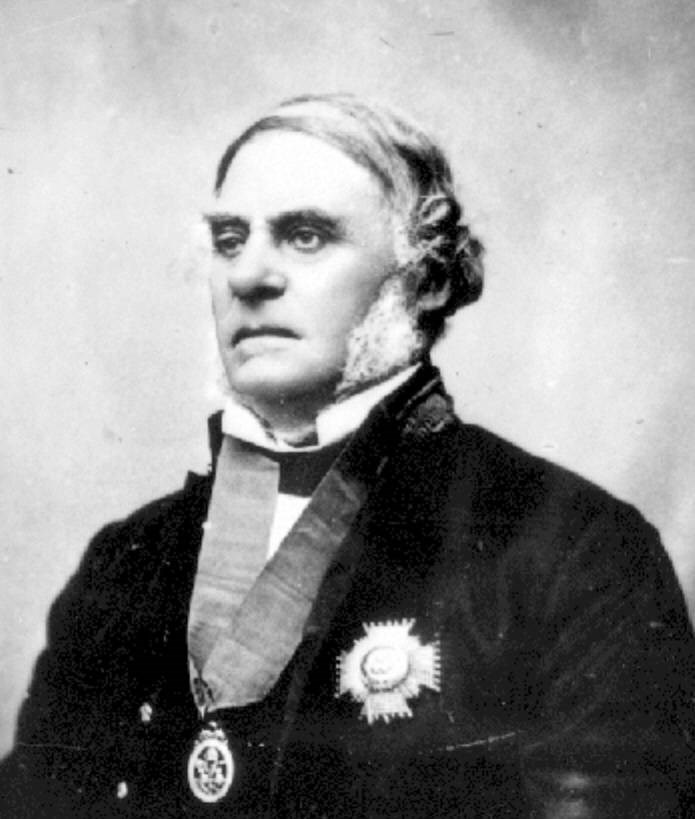

In the 1850s, James Douglas, the governor of the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, himself married to an Indigenous woman, made 14 small treaties, insisted that Indigenous people lay out their own reserves and have the same legal rights as Europeans, including the right to acquire more land.

subsequent governors, premiers and administrators reversed his policies. When British Columbia became a province in 1871 there were 10,000 settlers of European descent, some 3,000 Chinese immigrants and still some 50,000 Indigenous people, and yet the new settlers created a “white man’s democracy” where only European men had the vote.

Their promised “rule of law” was used to imprison those who persisted in the traditional potlatch, resisted colonization, and after the 1920s, it was used to force children into residential schools. Chinese, Japanese, immigrants from India and Black refugees from the United States also faced structural and blatant racism.

It is impossible to know, but we can imagine, what this territory would look like today if Europeans had treated the 40-some First Nations as sovereign bodies, as had Cook, Vancouver and Quadra, or if the land had been shared as promised by Douglas. What we do know is that at several junctions, settlers chose alternative paths devastating to First Nations.

And yet, there are some reasons to celebrate. Indigenous populations have finally returned to their pre-contact levels, their art and culture are deservedly world-renowned and celebrated and their concerns are now at the centre of provincial attention.

British Columbia is the envy of the world for our environment, standard of living, and our efforts to do better combating racism.

And surely there are reasons to mourn. As we mark this anniversary, the ongoing discovery of residential school graves are waking British Columbia settlers to inconvenient truths about our past and present. Most settlers are understandably appalled while many Indigenous people are being retraumatized. How can we move forward?

One thing is clear. Indigenous leaders have emphasized that the recent acts of vandalism are harmful to their aspirations to bring us together on a path to reconciliation.

“We do not believe in dividing communities” they said.

They have lived the harm done by attacking other people’s history and know there is no profit in disrespecting the histories of others. The people of B.C. are wise enough, and the province big enough, to accommodate multiple histories and we know that setting one story, one people, against another is the worst way to make progress.

We do not have to tear down earlier generations’ or another cultures’ heroes before we can raise our own monuments to tell new stories and point us in fresh directions.

Marking big-number anniversaries is an arbitrary act — especially when laid over thousands of years of Indigenous governance – yet we seem inexplicably drawn to them. This anniversary is useful in that it calls us to act.

Indigenous people will never be free to chart their own course until they have an economic and spiritual base of land and sea that allows them independence for their cultures to thrive unimpeded.

In British Columbia, a new, more fair and balanced treaty process would offer the potential to revisit James Douglas’s promise to share the wealth of the province and legitimize — both in the eyes of Canadian and Indigenous law – settlers’ continuing presence on unsurrendered Indigenous territory.

Write, text, email or call your MPs and MLAs and tell them to make it happen. When it does, that will be a time to celebrate.

- - -

To comment on this article, send a letter to the editor: [email protected]