The past month has offered an up-close look at freighters — those massive container ships that traverse the Juan de Fuca Strait and, too often lately, moor too close to shore.

On Jan. 2, the GSL Eleni was escorted into Victoria after losing its steering functions off the coast of Tofino. And two weeks ago, a second bulk freighter was forced to unload its cargo at sea after the vessel lost power and steering off the west coast of Vancouver Island. The 229-metre CSL Tecumseh ran into mechanical trouble after leaving Port McNeill with a load of sand and gravel aggregate.

Both serve as reminders of the potential hazards of shipping along the B.C. coast. The region’s coastal waters harbour enough hazards in the form of shoals, reefs, strong winds, fast currents, fog and storms without compounding them with mechanical problems, poor ship maintenance and human error.

The 2019 moratorium on oil tanker traffic provides some protection. It prohibits oil tankers carrying more than 12,500 tonnes of crude oil or persistent oil products as cargo from stopping, loading or unloading at ports or marine installations in the prohibited area — from the Canada-U.S. border in the north, down to the point on British Columbia’s mainland across from the northern tip of Vancouver Island. It also includes Haida Gwaii and protects the waters of Dixon Entrance, Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound.

It doesn’t cover vessels carrying lesser amounts of oil either as cargo or as fuel, vessels carrying other hazardous materials, or vessels of any size or cargo travelling through southern B.C. waters.

Indeed, if shipping were banned on the south coast, not only would Alberta once again threaten to turn off the petroleum taps, the resulting supply-chain issues would dwarf those experienced at the height of the pandemic and following the 2021 floods.

The establishment of marine response stations along the coast will help with oil spills. Having bases at Beecher Bay, Sidney, Nanaimo, Ucluelet and Port Alberni, as well as at Victoria, Vancouver and the Fraser River, will cut the time it takes crews to respond to marine spills. And that, history has shown, can help to limit the amount of oil spilled from a vessel and how far it spreads.

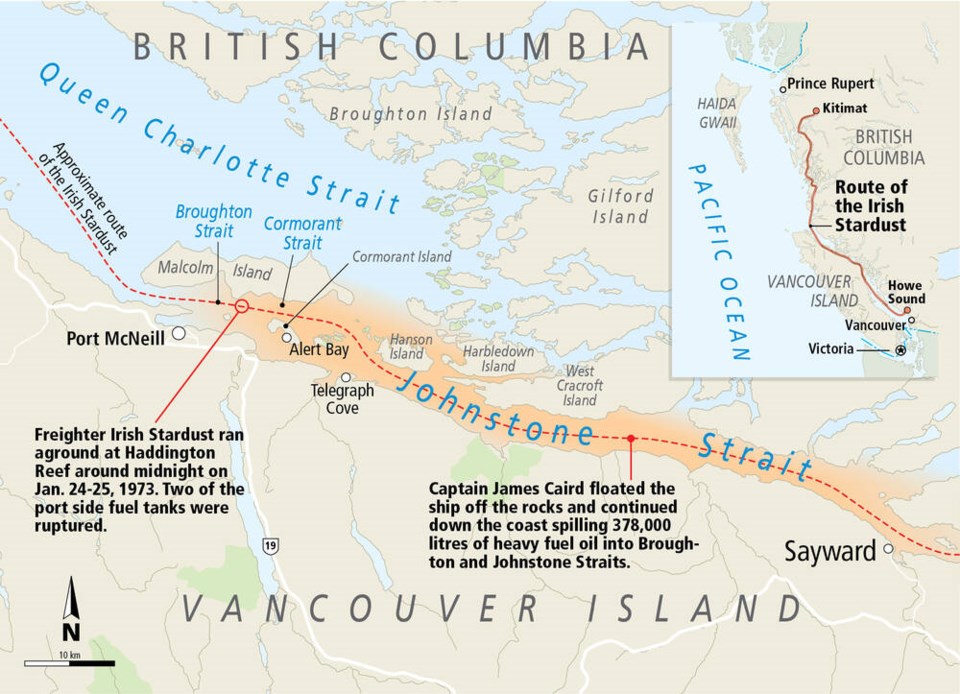

Take, for example, the case of the Irish Stardust. Fifty years ago, the freighter was heading from Kitimat to Howe Sound when it ran aground on Haddington Reef, near Port McNeill, around midnight Jan. 24-25, 1973. The impact damaged the Irish Stardust’s port side and ruptured two fuel tanks.

The captain, James Caird, floated the ship off the rocks and continued down the coast. He didn’t issue a distress call or report the spill.

As it travelled, the freighter leaked more than 378,000 litres of heavy fuel oil into Broughton and Johnstone straits.

High winds, chop and the tide did the rest. By sunrise, a swathe of oil covered a beach near Alert Bay. Residents reported the spill, and an armed forces patrol plane from Comox flew to the area to survey the spill’s extent.

A team of government specialists from Vancouver followed. They reported that the slick was visible from the air over 100 kilometres of Johnstone Strait and its small islands. One of the team was later reported as saying: “Everywhere you look, there’s oil. The water in Johnstone Strait is still about 25 per cent covered with oil.”

According to a government biologist who investigated the spill, if alarm had been given immediately and the ship had remained near the accident site, the spill could have been contained in a relatively small, manageable area.

Locals, including school kids, turned out to clean the beaches and shorelines. Three coast guard vessels reached Alert Bay quickly. But equipment and additional help were delayed, thanks to distance from the Lower Mainland bases and provincial and federal lack of preparedness. A federal contract with Clean Seas, a commercial company out of North Vancouver, to clean up the mess was promptly let, then promptly cancelled because the firm wasn’t equipped to handle the job. The governor of Washington state offered to loan its oil spill cleanup equipment.

Caird was charged under the Canada Shipping Act for leaving the scene of the accident, not taking proper action to minimize the spill, and failing to notify authorities of the spill within a reasonable time.

The ensuing court case was the first prosecuted in Canada under the federal government’s then-new anti-pollution laws.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]