Staff Sgt. Conor King has been a Victoria Police Department officer for 16 years, is an expert on fentanyl and other drugs from a law-enforcement standpoint, and serves in VicPD’s Investigative Services Division. He shares his thoughts on the province’s growing opioid crisis.

I spent Christmas 2015 sitting at my kitchen table, smartphone in hand, tracking overdose deaths across Greater Victoria. Eight people had died in seven days, three in the preceding 24 hours. Two of them died on the street, one in a parkade, the rest at home.

This included Miranda, the 22-year-old daughter of one of my co-workers at the Victoria Police Department. She died in her bedroom a few hours after opening Christmas presents with her mom and stepdad.

In the weeks before Christmas, I had watched the number of overdoses rise across the city. We call it a cluster. It wasn’t the first one I’d seen. That happened in the spring of 2013.

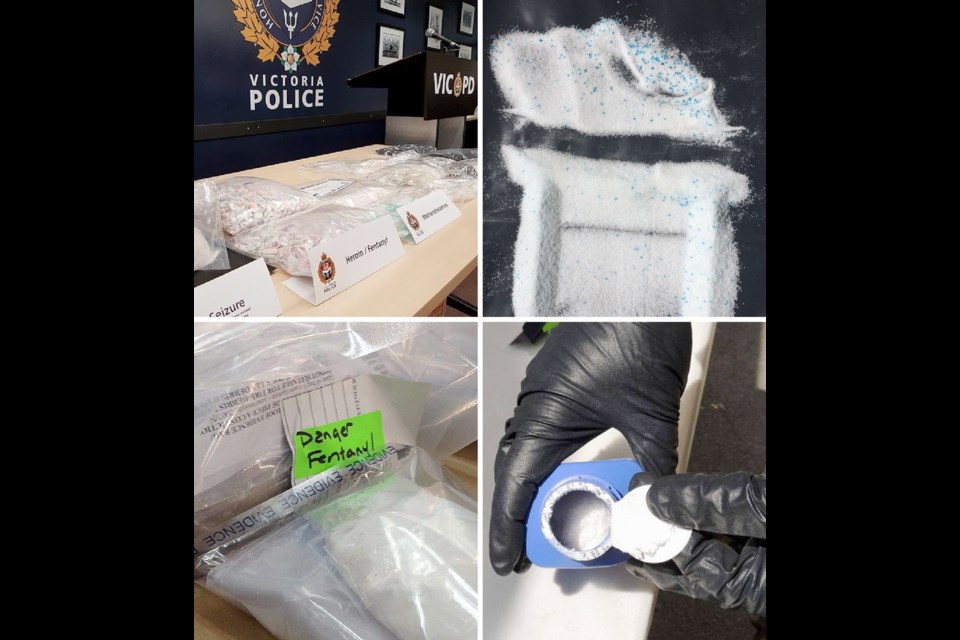

I was running a team of beat cops that patrolled Victoria’s downtown core. We started hearing reports from drug users about a new and powerful type of heroin. It was knocking them off their feet. Some people wanted it, but most were scared of it. My team managed to get a sample. I was startled when the drug tested positive for fentanyl. Back then, when someone mentioned fentanyl, I assumed they were talking about the tightly controlled pharmaceutical used as an anesthetic and pain reliever. This was different.

I called my friends at the RCMP. They invited me to an urgent meeting at their headquarters. Fifty cops and crime analysts from across Western Canada crowded into a briefing room. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration sent a team of chemists from Washington, D.C.

That’s not normal. I braced for bad news. On an oversized smartboard, we examined maps dotted with overdose clusters. Communities across North America were seeing overdoses spike. The chemists explained it was illicit fentanyl, cheaper than heroin and lethal in minute quantities. One held up a 500-milligram Tylenol tablet and said: “If this was fentanyl, it could kill 250 people.”

Despite the best efforts of police and border agents, heroin has been smuggled into Canada for decades. But I took some comfort in knowing how difficult this process was for criminals.

First, the actual production of heroin is labour-intensive. Cultivating the opium poppy, the source of heroin, is tedious and time-consuming. It happens in far-off countries such as Afghanistan and Colombia, so transporting it across the globe is complex and perilous. Smugglers’ boats sink, their planes crash, alert border guards search suspicious vehicles or a nervous airline passenger.

People take enormous risks smuggling heroin. That risk is a strong deterrent.

But what I was hearing from the RCMP was this: Unlike heroin, fentanyl is produced with ease by unscrupulous chemical companies in China and other countries, advertised on the Internet and shipped by commercial mail.

So, if you want to import a kilogram of heroin, you need to be plugged into an intricate network of international organized crime. If you want to import a kilogram of fentanyl, you shop online and get it delivered to your door — like ordering a new computer.

I walked out of RCMP headquarters fighting off a sense of dread. Sure, we’d all agreed to spread the word. Fentanyl’s out there and it’s deadly. People who use drugs need to be careful.

Except buying drugs isn’t like buying milk; there’s not much quality control. How can someone really learn much about the drugs they’re going to take, in a 30-second transaction that happens in an alley? One guy I knew, “Sonny,” was a small-time dealer. He sold just enough drugs to support his own habit. He lived in and out of homeless shelters for decades. He’d been through the crack epidemic in the 1980s and the crystal-meth scare in the 1990s. He knew more about addiction than most drug counsellors.

When officers found his body in a city park, syringe still in his arm, I only got more worried.

By Christmas 2015, someone was dying of an overdose in B.C. every day, double the rate of 2013. My daily routine included conference calls with epidemiologists, physicians and coroners. We tracked death by fentanyl as if it were a deadly virus racing across the province.

That’s how I learned about Miranda’s death. Unlike Sonny, Miranda had a good job and lived at home. She wasn’t naïve — her mom Lori made sure of that. After 20 years of working at a police department, Lori knew the importance of teaching her daughter about life’s rougher side. Lori and Miranda were close.

Miranda was supposed to spend Christmas Day in Vancouver, but she got homesick and travelled back to Victoria that evening. Her mom was thrilled and insisted she open her gifts before bed. Then, when everyone was sleeping, Miranda slipped out. She walked to a nearby gas station where she met her drug dealer. Miranda was dead an hour later.

Her death is like so many in this crisis. Miranda wasn’t addicted to drugs. She liked the thrill. But fentanyl kills indiscriminately. It doesn’t matter if you’re a longtime addict living on the street or an experimenting kid growing up in the suburbs.

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed. From the spring of 2013, when we first identified fentanyl in Victoria, to the end of 2016, it has killed more than 1,000 people in B.C.

This Christmas season, I’m again tracking overdose deaths from my kitchen table. But in the past year, B.C. has mobilized. My friends in the medical community and my colleagues in policing have united and are engaged in the battle of our careers. We’ll stop this epidemic and we’ll teach our counterparts in the rest of Canada what we’ve learned.