Who doesn’t love exploring a new word? For me the word “gamification,” as it applies to teaching and learning, set me off on a quest (my curiosity quest had already been “gamified” at this point) to find out more about the meaning and applications of “gamification” in a classroom context.

In recent years, as it turns out, the concept of gamification, defined as “the use of game design elements in non-game contexts,” has received increased attention and interest in both academia and classroom practice with education among the top fields of gamification research.

Before we go any further, gamification of learning does not involve students in designing and creating their own games or playing commercially produced video games in class.

Not at all.

The gamification of learning is an educational approach that seeks to motivate students by using video game design and game elements in learning environments. The goal is to maximize enjoyment and engagement by capturing the interest of learners and inspiring them to continue learning.

Examples of gamification applications in the classroom include awarding points for meeting academic objectives and grading “ forward” not “backward.” That means grading starts at 0 and moves forward accumulating points for goals accomplished instead of starting at 100 and deducting points or “marks” which would discourage most gamers from continuing for long.

In the same way while students may or may not need to be citing details from the text and evidence for conclusions in class discussions, answers without evidence are worth one point while a correct answer with one piece of evidence is worth two points, a correct answer plus two pieces of evidence earns three points and so on.

Gamification also includes creating challenges with more than one solution to a problem which is intended to emphasize divergent thinking as well as encouraging students to set their own goals, then track their own progress in a personal way.

Points can also be awarded for meeting procedural and non-academic objectives.

Need to solve a classroom issue such as shortening the time it takes to check homework? Students who have their homework out ready to be checked before being prompted by the teacher now receive two “bonus” points.

Gamification also encourages students to think about their thinking and to analyse how they arrived at an answer or solution to a problem in the same way that some video games, at the end of a game level, break down the player’s performance into countless details, total number of jumps, number of enemies alerted, number of different ways a specific problem was solved and lists ways to reflect and document their performance and compare with previous attempts.

Classroom gamification, broadly defined, is the process of identifying employing those design elements which make virtual games fun and which motivate players to continue playing, then using those same elements in a non-game context to influence learning behaviour.

In other words, gamification is the introduction of game elements into a traditionally non-game situation.

Some elements of games that may be used to motivate learners and facilitate learning include: player control, immediate feedback and opportunities for collaborative problem solving with other “players.”

Games of all types, both actual and virtual usually involve “scaffolded” learning with increasing challenges leading up a ladder of skills and concepts to opportunities for mastery.

Some of the potential benefits of successful gamification initiatives in the classroom include giving students ownership of their learning opportunities through the freedom to fail and try again without negative repercussions.

However, as the popularity of classroom gamification has increased, so have critical voices describing gamification as the latest buzzword and the next fad.

But proponents of the approach generally believe that the application of game mechanics and design such as feedback loops and rewards will become more embedded in daily life by 2025.

Perhaps the most persuasive argument supporting the gamification approach rests on the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

Intrinsic motivation happens when students enjoy learning for its own rewards, like the excitement of understanding a new concept or discovering a new skill as opposed to extrinsic motivation which occurs when students are motivated by external rewards or punishments.

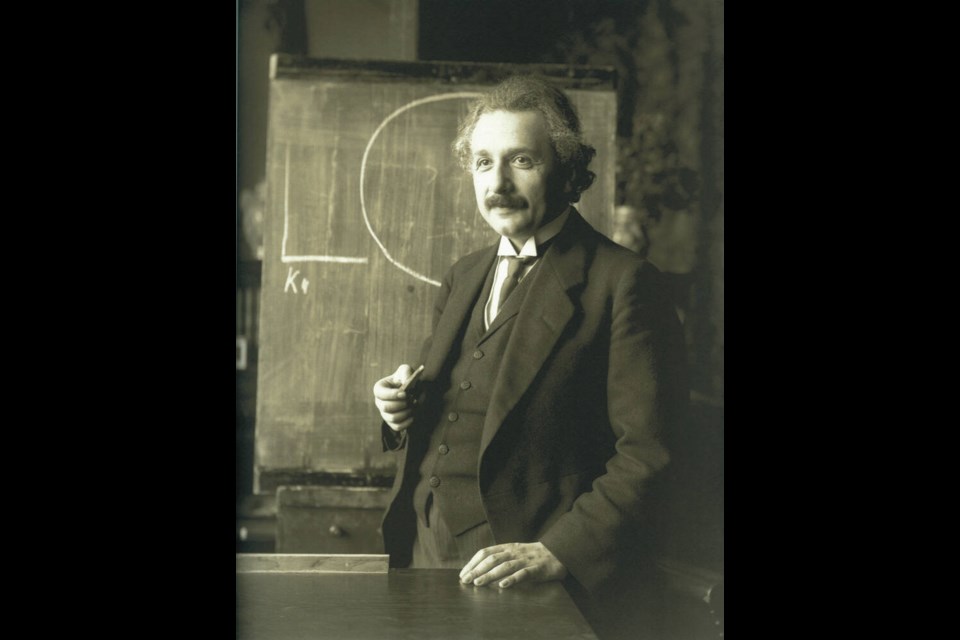

As Albert Einstein himself indicated, games are avenues for something deeper and more meaningful than a childish waste of time.

Games, Einstein insisted, are the first method children use to explore higher-order thinking skills associated with creating, evaluating, analyzing, and applying new knowledge.

And my own quest into learning more about “gamification” accomplished just that for me.

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools