Book banning is not new. In 212 BC, Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of unified China, burned all the books in his kingdom, retaining only a single copy of each for the Royal Library. Even those were destroyed before his death.

With all previous historical records destroyed, Qin Shi Huang thought history could be considered to begin with him.

More than 2,000 years later, the age-old tradition of book banning, if not burning, is alive and well and back in the local news again.

In September, a heated debate erupted among Chilliwack school trustees over who had the authority to ban books in B.C. school libraries.

One book at the centre of the dispute was All Boys Aren’t Blue — a series of personal essays by journalist and LGBTQIA+ activist George M. Johnson that explores the author’s childhood, adolescence and college years, and covers topics such as gender identity and toxic masculinity.

Three trustee candidates endorsed by the Chilliwack Parents Voice B.C., a new political organization, urged parents to “take back our schools,” a slogan with an all-too-familiar south-of-the-border ring.

It has always been so. Back in the 1960s, as a youthful enthusiast of edgy literature (please no more Jane Austen), I read James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man — the story of Stephen Dedalus, a boy growing up in Ireland at the end of the 19th century.

Joyce’s book caused the mildest of controversies at the time because of the central character’s rejection of Catholicism.

Intrigued by the story and by Joyce’s almost impenetrable style of writing, I attempted to move on to Joyce’s Ulysses — a much more controversial and almost unreadable novel written in a stream-of consciousness, basically unpunctuated, style. It turned out to be my first experience of trying to obtain a banned book, at least banned for me.

I was refused at our local city library because of the sexual content of the book and was told by the librarian to come back when I was much older (and presumably not as likely to be influenced by sexual content).

Over the years, and for a variety of reasons, minor authorities, motivated by a variety of philosophical and religious leanings, have tried to remove from public libraries and schools books and magazines that they deemed inappropriate for certain audiences.

An interesting look into all this is 100 Banned Books by Nicholas Karolides and others.

“Throughout history, tyrants, totalitarian states, church institutions and democratic governments alike have banned books that challenge their assumptions or questioned their authority,” Karolides writes. “Even today, attempts by school boards, local governments, and religious fanatics continue to restrict our freedom to read.”

At some points in the history of children’s literature, the book-banning movement has moved from the high-minded to the ridiculous.

During the 1970s and ’80s, zealous librarians began to limit their collections of Enid Blyton’s books.

The writer had been accused of sexism, racism and xenophobia, and her writings were deemed unfit for growing minds.

A senior Australian politician speaking in the House of Representatives opined that Blyton’s books illustrated “an inappropriate relationship between Blyton’s main characters Noddy and Big Ears.”

Nobody could make this stuff up.

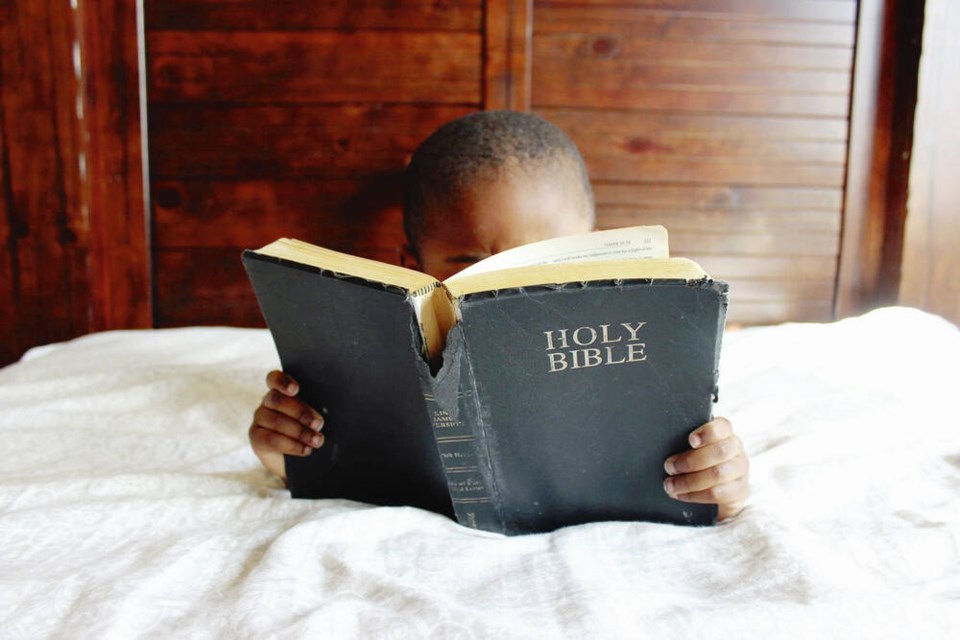

Incredibly, the Bible is still among history’s most censored books.

The most violently suppressed version of the Bible was the English translation by English biblical scholar William Tyndale.

Prior to Tyndale’s version, the Bible in Latin or Greek could only be accessed and interpreted by the priests of the Church of Rome.

Tyndale was arrested during a visit to Antwerp, tried for heresy, then strangled and burned at the stake near Brussels in 1536.

Translations of the Bible into the vernacular were subsequently outlawed in England and elsewhere for fear that they would lead to anarchy, schism and dissension, not to speak of a lessening of the influence of Rome on the minds of the faithful.

From July 2021 to June 2022, PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans lists an astounding 2,532 instances of individual books being banned in U.S. schools.

There are no such statistics for books banned in Canadian schools, but if Chilliwack’s example is any indication — well, stay tuned.

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.