A commentary by a retired physician who lives in Victoria.

I worked initially as a general practitioner for nine years, and then after four more years of training, as a specialist anesthesiologist for 30 years, almost all of my career spent on Vancouver Island.

The problems which are becoming increasingly obvious to patients seeking health care today have been building for decades, and have been painfully obvious to those working within the “system.”

The Covid pandemic certainly placed an unexpected burden on health-care providers and facilities, but there are far greater pressures which are continuing.

There have been decades of underfunding of medical and nursing health-care providers, as well as allied health-care workers, and facilities.

Even before Covid, Canada ranked fourth from the bottom in a list of acute care beds available for use per capita among 34 OECD countries.

Political leaders have touted a “free, universal health care system” to Canadians, while that system was failing before our eyes.

Not long ago the provincial government responded to the rising cost of health care by limiting physicians’ billing numbers and making it more difficult for nurses to obtain full-time employment. Obviously the problem was too many people providing health care to the public!

One only had to look at how many Canadians started Grade 1 in the 1950s; or look at the increasing costs of the advances in medical care (for example, cardiac stenting, pacemaking and bypass surgery didn’t exist in the 1950s) to realize there would be a tsunami of increasing costs which would arrive in the 2000s.

The most obvious problem in British Columbia is the desperate, and growing, shortage of family practitioners.

When I worked in medicentres in Edmonton in the early 1980s, an office visit was paid $25. Forty years later, the most recent fee schedule in B.C. lists payment for a GP office visit for patients aged 2-49 at $31.72 and $38.07 for the same patient as an out-of-office visit.

A friend recently had a kitchen faucet replaced. The bill for the plumber’s daytime, scheduled one-hour labour was more than $600. Is it any wonder family doctors are so disgruntled?

Many years ago I talked with colleagues who had worked under the NHS in Great Britain. Unlike Canada, Great Britain has a private alternative to the government funded system.

These colleagues predicted that the Canadian system would have to be in complete crisis before anything changed. Surely that crisis is truly upon us now.

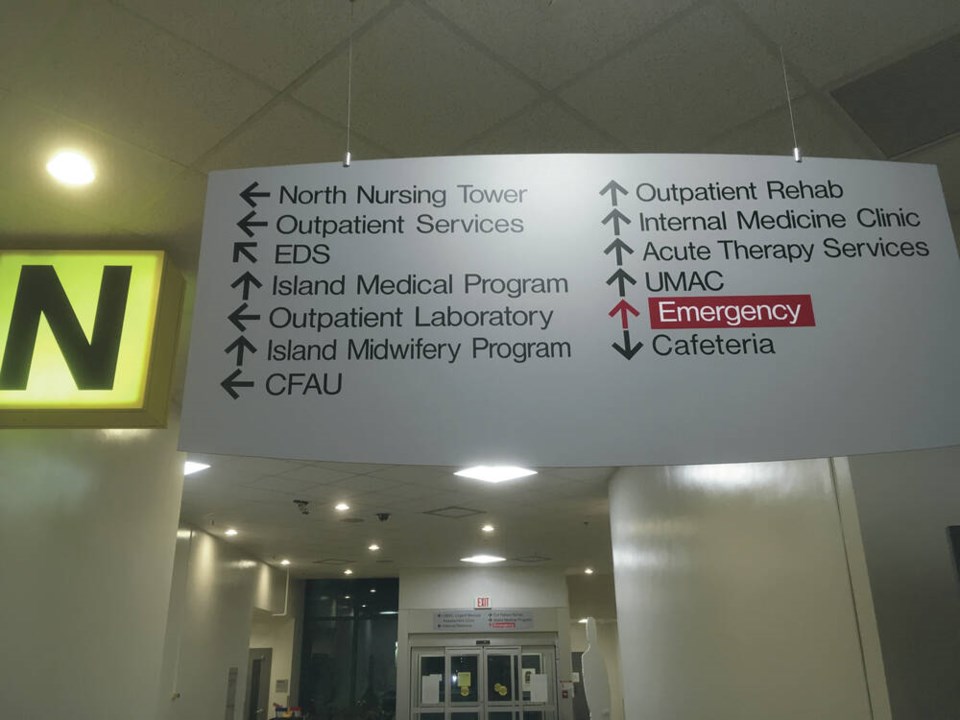

More than one million B.C. residents are without a family doctor. My wife recently spent from 6 p.m. until after 1 a.m. in the Victoria General Hospital emergency ward with her elderly mother, who needed an antibiotic for a cellulitis in her arm (something I had diagnosed the day before, but could not write a prescription to treat).

She has a family doctor but could not get in to see him, and urgent care centres were also unable to see her. There were 80 patients waiting when they checked in.

Many, if not most, of those patients could have been treated by a family doctor or urgent care centre visit, if that was actually availble to them.

A recent Times Colonist front-page story described pregnant women in south Vancouver Island “scrambling” to find maternity care, as the number of maternity GPs has dwindled from 48 to 25, and midwives are retiring and not being replaced.

Then it was announced that B.C. patients with breast and prostate cancers will be sent to the United States for treatment, at a cost of many millions – money that should be spent providing the infrastructure needed and adequately compensating the practitioners who provide such care here.

Providers of women’s health care describe a two-month waiting period to have an IUD contraceptive device placed in B.C.

Recently Health Minister Adriaan Dix stated how pleased he was that the Supreme Court of Canada had dismissed, after a 14-year legal battle, the appeal by Vancouver orthopedic surgeon Brian Day of the B.C. Supreme Court decision to deny British Columbiams access to a private health-care alternatives in the face of long surgical waitlists.

The same Supreme Court of Canada, in 2005, in the “Chaouli” decision found that the Quebec Health Insurance Act and Hospital Insurance Act prohibiting private medical insurance in the face of long wait times violated the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms.

Ironically that court tied on the question of whether the rest of Canada should have similar rights protected, and the Day decision (in 56 words) seems to have confirmed that double standard.

Similarly the health minister was pleased that family doctors who had opted to offer services privately had been forced to return to the fold. And now Dix has announced a multi-million dollar program to send British Columbia patients south of the border.

Whether via private alternatives or significantly increased government funding, far more will be required to care for Canada’s growing, aging population.

The current “universal, free health-care system” emperor has long since lost his clothes. When will the Canadian public. and the people they elect to make decisions on their behalf, finally realize it?