It wasn’t the New Year’s Eve party they’d expected. When Victoria residents J.J. Kavelaars and his wife arrived at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, late on Dec. 31, the celebration they had dressed up in suit and gown for turned out to be science lectures.

Specifically, it consisted of four hours of lectures about the Kuiper Belt, the field of space rocks and planetesimals — large rocky space objects too small to be planets — orbiting the sun far beyond planets Neptune and Pluto.

Kavelaars, who studies the Kuiper Belt and other aspects of the outer solar system from his lab at the National Research Council in Saanich, was delighted.

“I’ve never been at such a fun New Year’s Eve party,” he says. “It was a bunch of geeks hanging out together, enjoying the experience.”

But he had brought his wife — not an astronomer. He told me afterward: “I said to her: ‘I don’t know how I managed to trick you into flying across the continent to go to a New Year’s Eve party that was actually a lecture.’ She was sitting there in her ball gown that she bought for New Year’s Eve, and she said: ‘I feel slightly inappropriately dressed, but it is interesting to be here.’ ”

The evening’s program also included a countdown to midnight. However, the main event would take place 4.5 billion kilometres away. Kavelaars, the other scientists, engineers, dignitaries, journalists, and their families had come to this New Year’s Eve party because, at 12:33 a.m. Maryland time, the New Horizons space craft would begin flying past a Kuiper Belt object nicknamed Ultima Thule.

They had helped New Horizons get that far, were guests or were reporting on the event.

And, because the mission’s success wouldn’t be confirmed until the spacecraft’s radio signal reached Earth hours later, it wasn’t until about 10:30 a.m. that the mission team announced the spacecraft’s first signal from Ultima Thule had been received. “We have a healthy spacecraft. We’ve just accomplished the most distant flyby.”

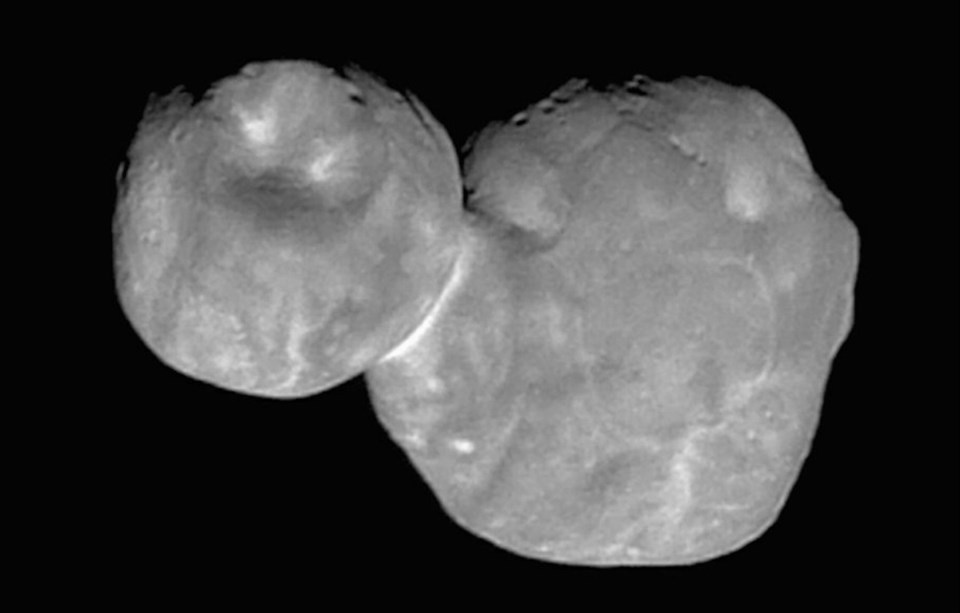

Low-resolution images of Ultima Thule followed.

The contributions of Kavelaars and colleagues who’d worked on an earlier project called the Canada-France ecliptic plane survey were key to this leg of New Horizons’ mission. They had told the mission team where and how to find Ultima Thule.

“In the mid-2000s, we did a large survey of the outer solar system,” Kavelaars says. “We were trying to collect an ensemble of Kuiper Belt objects that would allow us to model the structure of the outer solar system in a statistically robust way.”

They used information from each new discovery of a Kuiper Belt object to create a mathematical model that predicts where Kuiper Belt objects are located, how big they are, what their orbits are and how they change with time.

They published the model in 2007. Shortly after, the New Horizons group put out a call for help. The mission group had been searching for a Kuiper Belt target for the spacecraft for several years. With New Horizons already on its way to Pluto — its first planned encounter — work needed to start on Phase 2 of the mission plan.

“We did an analysis using our model and suggested a slightly different place in the solar system where they could look — a very small tweak from where they had been looking,” Kavelaars says.

“We also better understood the distribution of sizes of material by then, so we told them: ‘You have to look in this little spot a bit differently, and you have to look more faintly, because there aren’t many bright objects.’ ”

The mission team used the Hubble Space Telescope to search the co-ordinates submitted by the Canadians. They found a Kuiper Belt object exactly where and at the brightness Kavelaars and his colleagues had said it would be. That object was Ultima Thule.

Now, six weeks on from New Year’s Eve and New Horizons’ encounter with Ultima Thule, work on the project is gearing up for Kavelaars and other New Horizons researchers. Information from the spacecraft is beaming in, with high-resolution data expected through the next 20 months. Images received of rocky, conjoined lentil-shaped Ultima Thule will help Kavelaars and others better understand the solar system’s outer reaches, how Earth and the other planets formed, and what the early solar system was like.

Stay tuned for more dispatches from the Kuiper Belt.