This is the last in a series of columns about the Great War that ended 100 years ago Sunday.

At the time, the conflict was called the war to end all wars. The common sentiment among its combatants was: Never again.

But regrettably, that’s not how things turned out. Humanity’s greatest self-inflicted calamity up till that time did not bring an end to such madness. On the contrary, it was only the beginning.

Just about every combat fought since 1918 has owed its origins to hateful ideologies spawned by the war, or in settlements imposed on the Middle East, which fatally deranged an already volatile region. In short, the darkest of pictures.

But there were a few points of light, and I want to conclude by mentioning three.

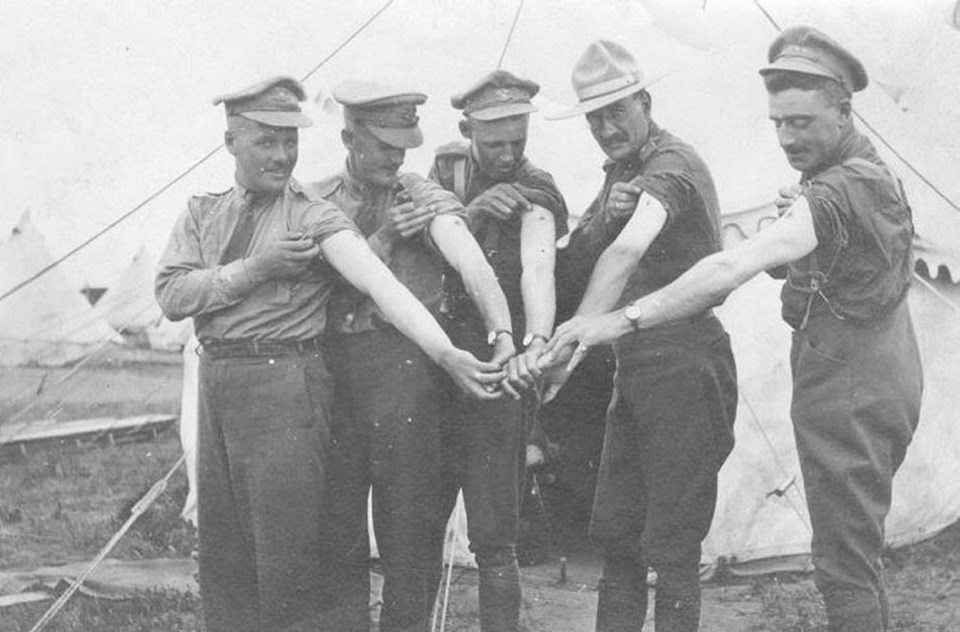

It is generally recognized that the Great War witnessed Canada’s arrival on the world stage. I’m not sure this is how any of us would want to remember our passage into adulthood. Nevertheless, the willingness of young Canadians to enter the fray and the casualties we suffered (higher per capita than any of the other combatants), marked our emergence from the shadow of colonialism into the community of nations.

The second betterment involved the realization that something had to be done about the health of working men and women. In Britain, when conscription was introduced, tens of thousands of young men were turned away from recruiting stations because their state of health was dreadful.

Poor eyesight left untreated, the prevalence of ailments such as rickets caused by lack of nourishment (I recall as a university student in Dundee seeing elderly men and women bowlegged with this disease), infestations of parasites and heaven knows what else appalled the medical community.

It was this wake-up call in Britain that sparked calls for a national health service, although it took a second world war to finally generate action.

Canada, too, introduced conscription, and here as well, though not to such a degree, public health became an issue. In effect, this was the first time our governing classes were brought face to face with the reality of widespread ill health throughout the working poor.

Canada took longer than the U.K. to introduce universal health care, but it’s not a stretch to say that here, also, the war opened eyes that had previously been averted.

The third positive outgrowth was the culmination of the suffragette movement. That women should be denied the vote sounds ridiculous today. And in both Canada and Britain there were militant demonstrations before the war that made some minor gains.

But when women stepped forward to take on wartime jobs previously thought too strenuous for the “weaker sex,” the case for universal suffrage become unanswerable.

That women could replace men in armament factories, work as truck and ambulance drivers, and generally make an invaluable contribution to the war effort, essentially ended the debate.

There were some ugly exceptions. Most women in Canada were granted the right to vote in federal elections at the close of the war. However, that right was not extended to Indigenous women (or men), until 1960. Canadians of Asian birth were also left out for several decades.

Nevertheless, in all of these instances, despite the horrors of the Great War, progress was made.

There is no forgiving the “statesmen” who led their nations into unspeakable horror, or creatures such as Stalin and Mao, Hitler and Mussolini, who exploited the calamities and convulsions it brought.

The world we live in today has been rendered infinitely more dangerous by the legacies of that conflict. We are a more distrustful species, quicker to anger and readier to play for suicidal stakes, than at any time in our history.

But this Sunday morning, as we pay our respects to those who died believing in a greater good, it is worth remembering that some good did actually occur.