It’s taken David Brown almost two years to talk about the death of his father.

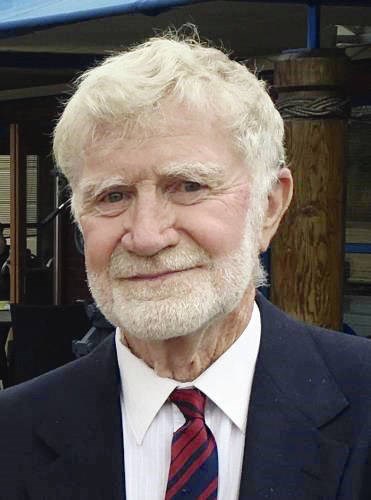

Arthur Aubrey Brown was murdered in November 2018 in a remote Mexican village in Jalisco province where he wintered every year. The 82-year-old Victoria widower liked to escape the dreary West Coast winters and sit in the warmth of the Mexican sun.

“He rarely ventured out. Certainly, my father never thought he was at any risk,” said Brown.

But he was. The much-loved father and grandfather, who retired in 1997 after a 23-year career with the Environment Ministry, was the victim of a home invasion on either Nov. 18 or 19.

“As far as we know, he was surprised in his house,” said Brown. “They forced their way in and killed him in the house. They took him and his car and drove it off the road down a steep ravine to make it look like an accident.”

An autopsy later confirmed his father died from blunt force trauma.

With only rudimentary Spanish, the family reached out to Global Affairs to help them find out what happened. A case officer was assigned to represent the Brown family in their dealings with the Mexican authorities.

“We somewhat naively had the idea that the Government of Canada could go to great lengths to help us, but their ability was somewhat limited,” said Brown. “The case officer told us right away that probably 90 per cent of these homicides are unresolved. In 2019, they had 35,000 homicides [in Mexico].”

Brown, accompanied by his brother and sister, flew to Mexico the week before Christmas 2018 to bring their father’s body home.

The Mexican government insisted that they travel to the remote village of Cihuatlán, a four-hour drive from Puerto Vallarta, to give a statement in person to the authorities. The Canadian government told the authorities that the family wanted to give the statement in Puerto Vallarta because they were afraid for their safety, especially in light of what happened to their father. But the authorities would not budge, said Brown.

“Then we asked someone from the consulate to accompany us, because we would have felt safer, but their position was that if they couldn’t be back in Puerto Vallarta by dark, they then couldn’t go. It was a bit of a tough thing,” said Brown.

“We didn’t know the language, the culture, the law, their criminal system or their medical system. We felt it was trial by fire.”

The family hired a local lawyer and she arranged for a driver to pick them up in Puerto Vallarta at 6 a.m. and drive them to Cihuatlán to make a statement to the district attorney. Essentially, the lawyer read out and translated the statement Brown had already given to the Canadian government, he said. “It was a bit of a comic show.”

But after the statement, the authorities agreed to release his father’s remains without the requirement of viewing the body.

Later that morning, Brown and his siblings went to their father’s house in nearby Boca de Iguanas and discovered that police had not even been there to investigate.

“It was very distressing to have to go to the house where he died so police could do their investigation,” said Brown. “They were there for hours doing their forensic evidence. This was five to six weeks after the fact. There was probably very little forensic evidence.”

The hours passed and it began to get dark. At that point, the police wanted another statement, said Brown. They also wanted to be fed.

“The lawyer turned to us and said: ‘The police want to know when you’re going to buy them dinner.’ I said ‘What do you mean?’ And she replied: ‘Well they’re hungry. They haven’t eaten all day.’ And all I’m thinking is if my house in Victoria was broken into, it would be like the RCMP saying: ‘Oh come on, David. We’ll investigate, but you’ll need to feed us.’ ”

Brown had given all his cash to the locksmith to change the locks on the property.

“I literally had no money. But it’s just a sign of how poorly paid their police are.”

They drove back in the dark on the single-lane highway, arriving safely in Puerto Vallarta later that night.

The family discovered that all of Arthur Brown’s identification — including his passport and long-term birth certificate — had been stolen. His bank account with about $4,000 Canadian had been cleaned out. A series of cheques had been written against his father’s account.

The family also had to deal with a funeral home in Puerto Vallarta that said it specialized with repatriating remains of North Americans. They made all the arrangements, but forgot to contact the funeral home in Vancouver to let them know.

“They just didn’t think of it,” said Brown.

Global Affairs was very good at helping the family navigate the paperwork, he said. But there’s been no follow-up on his father’s murder.

“Honestly, It’s been hard. There hasn’t been a day since this happened that I don’t think about what happened to my father,” said Brown. “I remember listening to an interview with the widow of a 9-11 victim and they were asking her: ‘How do you deal with this?’

“The reality is, you just find a way to live with it. Over time, the rawness of the situation diminishes, the intensity of emotion. But you never forget. There’s no playbook for dealing with this.”

Brown realizes that sharing his story won’t change people’s minds about travelling to Mexico. His father’s friends and acquaintances continue to winter there.

“Most people don’t read travel advisories. I’d gone down to visit my father, but I never read the travel advisories. The part of Mexico where he was staying is very beautiful. People go down there to escape the weather. The local people are lovely, the language is beautiful and you can live like a king.”

People can take what they want from his story and make their own decisions, said Brown.

“I think as Canadians, we have this expectation that if you get into trouble in another country, our government will go to great lengths to help us out. The reality is it’s the laws of that country that govern what happens. The law of the land rules.”