Eighteen years later, James McCallum is sustained by hate.

Hate for the man who murdered his teenage son in a Gorge Road parking lot. Hate for the system.

That's the way it was when we checked in on him in 2002. That's how it will be tomorrow. At 62, rage is what keeps him going.

"Absolutely," he says. Will he change? "No, I never will."

Right now, his anger is focussed on how hard it was to find out that Canada did, in fact, deport his son's killer this summer. Deportation is a hot topic these days as Bill C-43, the Faster Removal of Foreign Criminals Act, works its way through Parliament.

James's life changed Sept. 17, 1994, as he and his 18-year-old son, Trevor, with whom he worked as a roofer, were backing out of the parking lot of the Gorge Road Tim Hortons. A man ran behind the McCallums' truck, drawing an admonition from James. The man turned out to be one of 11 young people from a nearby van.

Things escalated. When the van passengers began surrounding Trevor, James brandished a shovel to keep them at bay. As Trevor climbed into the passenger side of the truck, Hung Quoc Hoang, 22, fired a sawed-off 12-gauge shotgun. Trevor died in his father's arms.

James chased the van as it sped off. He hoped to ram it, but it got away. Police said they believed it was people in the van who later that night shot at a home on Cook Street.

Eighteen years later, the pain is still fresh. James wears Trevor's old Mondetta jacket, stolen during a car break-in in 1993, only to be discovered by James in a thrift store in 2001 (he identified it by a speck of tar that still clung to the fabric). He holds on to Trevor's artwork, including his last piece, an unfinished sketch of an angel. The emotion of it all brings tears to his eyes.

Six Vancouver-area men were charged with Trevor's murder, but charges were stayed against five of them. In 1996, Hoang, a landed immigrant from Vietnam who had come to Canada at age 15 after three years in a refugee camp, was convicted and sentenced to life. The van driver got three years probation. The others walked free.

McCallum's experience with the justice system, with government, left him seething. He no longer pays income tax because of it.

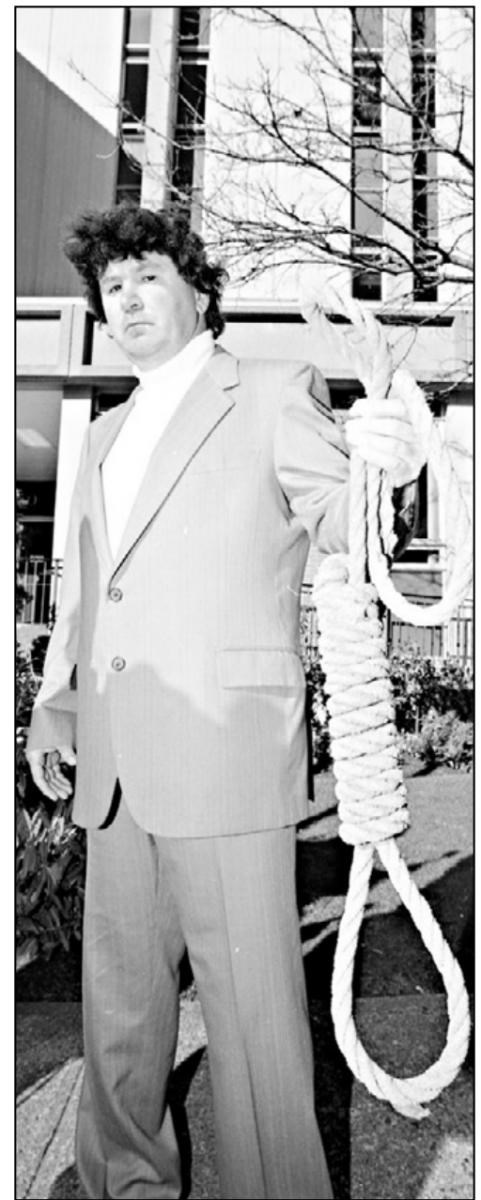

"They let nine accessories walk. Why should I pay taxes?" In 1996, he was photographed with a noose, calling for a return of capital punishment.

His internal torment intensified this spring when he was told that Hoang was up for parole. McCallum's reply was: "I want a letter saying he's going back to Vietnam." We can't do that, the authorities replied. Privacy issues.

McCallum was beside himself, not knowing what had happened to Hoang.

"If you were in my position, how would you like walking the streets, knowing he's out there?" he said. "Why should I have to wonder when I go to one of my vehicles at night whether somebody's going to pull a gun and take me out?"

He says it shouldn't have taken a shove by lawyer Doug Christie to get confirmation in September that the Canadian Border Services Agency had deported Hoang upon his release from prison on July 24. "The system's got to be here for the victims, not the criminals."

It's easy to sense McCal-um's anguish; none of us would want to find out how it feels to be him. It's also easy for Canadians to be offended by stories like Hoang's: The nation opens its arms to a refugee, only to be repaid with violent crime.

The Conservatives have reacted to stories of lawless immigrants with Bill C-43, which would make it easier to quickly deport people with permanent resident status who are convicted of serious crimes. Currently, those sentenced to less than two years in prison can appeal deportation orders to the Immigration Appeal Division; the new law would allow only those sentenced to less than six months to do so. Authorities would no longer distinguish between conditional sentences - those served at home - and those served in prison. The government says the aim is to prevent bad guys from continuing to commit crime as they string out the appeal process.

But critics say the bill is disproportionate to the threat, that it panders to xenophobia and a sense of injustice that isn't rooted in fact. Canada already deports plenty of non-citizens convicted of serious crimes: 1,911 in 2011-12, including 331 from the Pacific region.

The Canadian Bar Association says there is no evidence of the kind of widespread abuse of process that would justify C-43's "one-size-fits-all denial of appeal rights." It says the new law leaves no place for common-sense discretion.

Whatever the outcome, it won't change James McCallum's reality. His son is gone. His grief remains.