The family of a man shot dead by RCMP in Port Hardy is frustrated that the officer who delivered the fatal shots didn’t complete training in de-escalating conflicts.

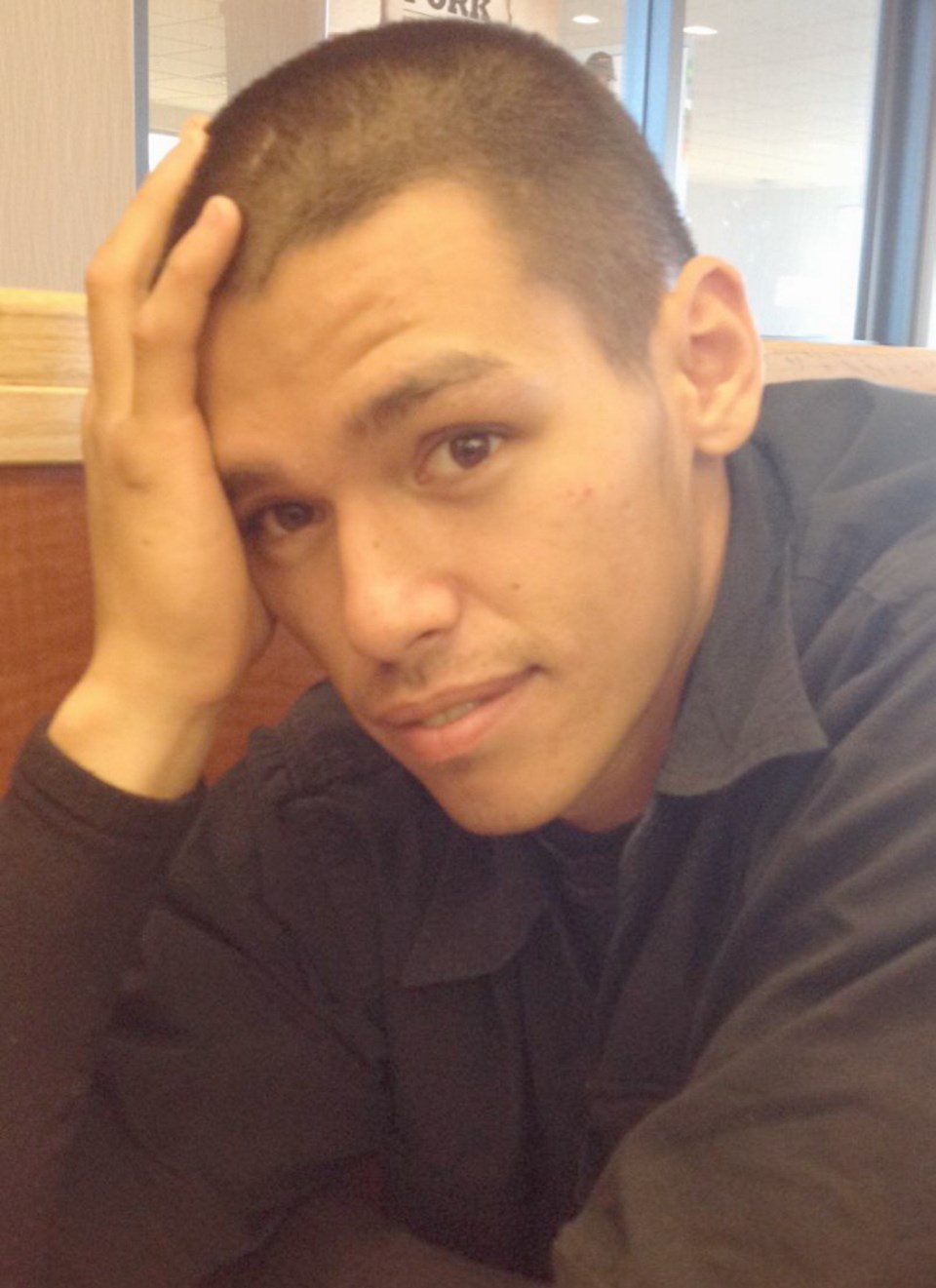

James Butters, also known as James Hayward, was shot five times on July 8, 2015. Police were answering a disturbance call and the 24-year-old ran at one officer with a knife.

Butters’ aunt, Nora Hayward of Lake Cowichan, attended a B.C. Coroners Service inquest last week into her nephew’s death. Hearing that the officer involved never completed training in critical incident de-escalation was especially hard.

“The mandatory training had not been done when James was shot and it had not been done when [the officer] testified,” Hayward said Wednesday.

“[The officer] said he didn’t think of it. It was a very nonchalant answer.”

Hayward said an expert in police use of force testified that crisis de-escalation training for police officers is mandatory in B.C. and it would be rare for officers without it to even be on active duty.

The jury at the coroner’s inquest into Butters’ death sat for six days beginning Aug. 20. It made seven recommendations, including one that the requirement for de-escalation training be enforced in B.C.

Dawn Roberts, spokeswoman for the B.C. RCMP, said the recommendations from the inquest will be reviewed and a response sent to the B.C. Coroners Service.

The Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General, responsible for police in B.C., said it would look carefully at the jury’s recommendations.

B.C. coroner’s inquests are not about assigning blame — they are fact-finding exercises by juries, which can make recommendations to prevent future similar deaths.

The jury at Butters’ inquest also recommended that prescription medicine for a prisoner’s safety and well-being be provided after release from jail.

Hayward said the inquest heard that Butters was on medication to assist with his mental health when he was in the Vancouver Island Regional Correction Centre in 2013 and 2014.

But when he was released, Butters could no longer gain access to that medication, despite a jail-time request that he be allowed to continue.

Hayward said after his release, Butters was told he would have to see a psychiatrist, which was difficult to arrange in Port McNeill, where he lived. It would be up to a psychiatrist to prescribe the medication.

“The drugs he was taking just before his discharge were working for him,” she said. “But when he got out, he wasn’t able to get them.

“There was just a whole bunch of little blips and bloops in his way and he wasn’t able to get the medication.”

The coroner’s inquest jury recommended processes be reviewed to ensure a continuity of care between jail and the community.

Other recommendations included training for probation officers to assess risk for clients with mental-health issues.

Hayward said her family understands Butters was difficult. He had a criminal record and had been in jail. He also had diagnosed mental-health issues and a history of substance abuse and addiction.

But when Butters was killed, he had neither alcohol nor illegal drugs in his body.

With the inquest now over, Hayward said she believes her nephew can be at peace. The jury listened, asked good questions and made thoughtful recommendations, she said.

“The jury sat for six days, listened and talked about James,” Hayward said.

“I really believe he was heard.”