With the Opposition demanding her resignation, Children and Family Development Minister Stephanie Cadieux announced Monday that the government will report publicly twice a year on the numbers of foster children who have to be placed in hotels.

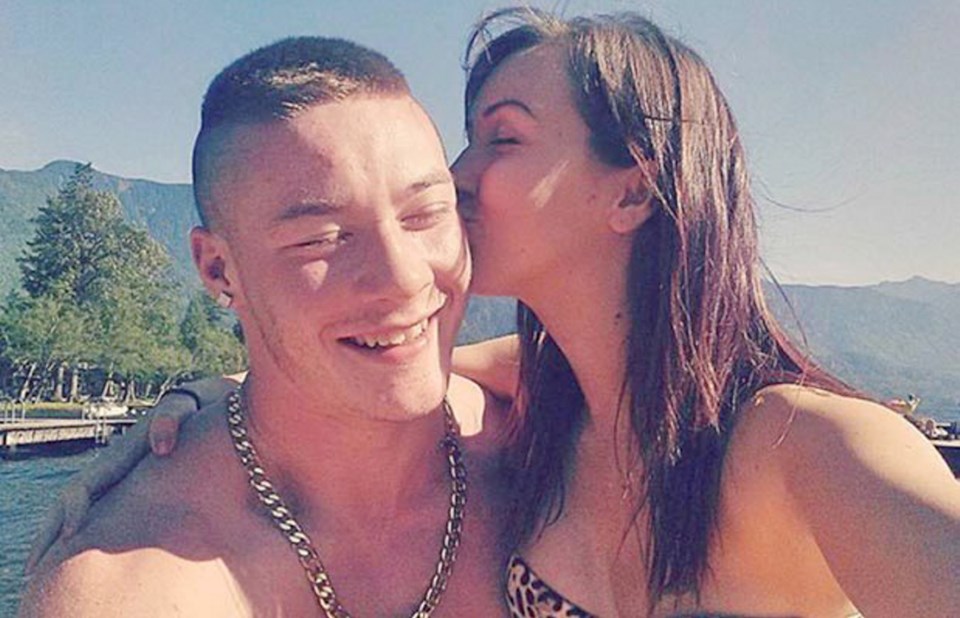

The move comes following the death of 18-year-old Alex Gervais, who fell from a fourth-floor window at an Abbotsford hotel where he had lived alone while in the ministry’s care.

Cadieux told the legislature that front-line staff were told numerous times that hotels were not to be used for housing children and youth.

“Hotels are and only are to be used in extreme circumstances and only with approval of the designated director and notification to the provincial director of child welfare, who will monitor those situations,” she said.

Without commenting directly on the Gervais case, Cadieux said that when a number of resources closed and 33 children needed a new place to live, the provincial director of child welfare approved new care plans. “Not one of those plans included a stay in a hotel,” she said.

Cadieux said a review is underway to determine “exactly what went wrong” in the Gervais case.

Fraser Valley Aboriginal Children and Family Services Society, an agency contracted by the provincial government to protect foster children, was responsible for the teen’s care. He lived for months in an Abbotsford hotel — in violation of government policy — before falling to his death Sept. 18.

The agency, formerly named Xyolhemeylh, was co-founded nearly two decades ago by Grand Chief Doug Kelly of the Sto:lo Tribal Council, who later became a vocal critic of the agency after a series of missteps, including the death of a toddler.

“The agency was working with young Mr. Gervais, trying to find a way of helping [him] to be prepared for being an independent 19 year old. Did their efforts succeed? Clearly not,” said Kelly.

“Are the agency and social workers hurting? Absolutely. Are they asking themselves those very difficult questions: Did I do everything in my power to help Alex? They are all suffering that painful reflection. So we have to make sure we build on improving services.”

Today, Kelly — who is also chairman of the First Nations Health Council — and other native leaders are working with the agency to improve child-welfare services. He won’t discuss the specifics of the Gervais case, but said foster youth must no longer be placed in hotels, and argued the government needs to beef up funding for group and foster homes so there are other alternatives.

“I regret that our agency and that the Ministry of Children and Family Development were not able to provide young Mr. Gervais the support he needed,” he said. “I’m sorry that his life ended far too soon.”

Kelly, who met Monday with the society’s executive director and board chairwoman, said the agency will co-operate with all reviews by the provincial director of child welfare, children’s watchdog Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond and the coroner.

The government has put its trust in the society, one of a handful of delegated agencies in B.C. that has the highest level of child-protection authority, including removal from homes and placement in care. A 2012 ministry audit said the agency was responsible for 334 children and was offering resources to another 193 at that time. Its 2010 annual report (the most recent available on its website) said it received $22 million in annual funding from the government.

And yet the agency once known as Xyolhemeylh has had a difficult past.

It was responsible for 23-month-old Chassidy Whitford when she was killed by her father on the Lakahahmen reserve near Mission in 2002. A provincial review found the agency did not meet child-protection standards, in part because the toddler was allowed to continue living with her father despite unexplained injuries.

Four years later, in 2006, former chief Jimmy George stepped down as head of the society that ran the agency after it was made public he was convicted of sexual assault on at least one Chilliwack girl in the 1980s. George would be convicted again in 2010 for sexual interference with another youth.

The Chassidy case and other developments triggered a nasty fallout between Xyolhemeylh and some native leaders, such as Kelly. Agency social workers were banned from some reserves.

The ministry took over the troubled agency in 2007 and full child-protection powers were not restored until 2010, after Gwendolyn Point, Chancellor of the University of the Fraser Valley, was appointed chairwoman of the board.

But the newly named Fraser Valley Aboriginal Children and Family Services Society still struggled for years to gain support from prominent native leaders.

Kelly, who now works with the agency, is angry Premier Christy Clark said last week it would face “consequences” for its role in Gervais’s death, rather than withholding her comments until a series of government reviews are completed.

“She has hung my agency out to dry,” Kelly fumed.

“She has come out and made a pretty significant threat statement to a delegated agency without having the facts. She essentially slapped the agency across the face with a closed fist. She also knows the agency’s hands are tied behind its back. The agency can’t talk about the young man or what they were doing with him because of confidentiality.”

Kelly also argued the ministry is not blameless, since it oversees the agency’s contract to provide child-welfare services and has an underfunded budget that cannot provide enough resources to foster children.

Cadieux said it’s “too soon” to know who, if anyone, at the agency should be disciplined, and that it may be months before her director completes a review.

“The reviews are underway and when they have been concluded is when we will know what consequences will be necessary, whether that be particular individual … consequences, or whether or not there is policy and practice implications on a larger scale,” she told reporters.

Cadieux wouldn’t say if the agency’s past problems would form part of the review, saying that’s “up to the provincial director.”

Ministry policy directs that no foster children be placed in hotels without approval of the director of child welfare, which was not followed in Gervais’s case. Such emergency placements were used at least two dozen times this year.

Cadieux spent the day on the defensive at the provincial legislature, where she was grilled by the Opposition NDP on her ministry’s failings in the Gervais case.

NDP Leader John Horgan called her performance as a minister “pathetic,” and demanded she resign.