Victoria historian Mark Zuehlke once trudged 300 kilometres through Sicily in the mid-summer heat.

And he’s got the souvenir sweat stains to prove it.

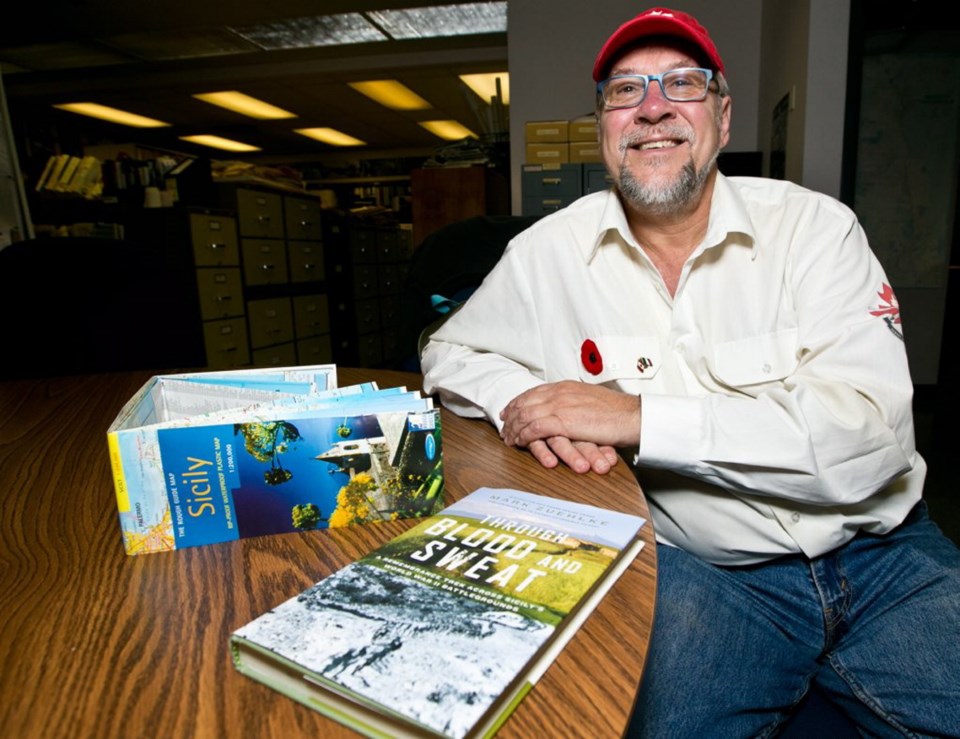

A few days ago, Zuehlke donned one of the military-style shirts he and nine other Canadians wore while marching though the hills of Sicily in July 2013. They undertook the 20-day trek to commemorate Canada’s participation in the 1943 Allied invasion called Operation Husky.

Under a blazing Italian sun, with Mount Etna in the background, Zuehlke and his companions grappled with temperatures as high as 43 C.

“That’s why my shirt is so grimy,” he said with a grin. “It’s got these lovely sweat stains.”

Douglas & McIntyre just published Zuehlke’s Through Blood and Sweat, the award-winning author’s 248-page account of the experience.

On Remembrance Day, Canadians will gather from coast to coast to pay tribute to our country’s fallen soldiers. Many will think back to the Battle of Vimy Ridge or the D-Day invasion of the Normandy coast.

Less well-known is Canada’s participation in the invasion of Sicily from July 10 to Aug. 7, 1943, known as Operation Husky. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division and 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade joined other Allied forces for the operation. The landing was successful; however, troops soon encountered resistance from crack German troops. When the dust cleared, 562 Canadian soldiers were dead.

The 2013 commemorative trek was the brainchild of Steve Gregory, a Montreal businessman. His son, Eric, had completed a high school project on Operation Husky. Afterward, Gregory took his family for a vacation to Sicily, where they visited a cemetery for Canadian soldiers.

The businessman became so enthusiastic, he decided to organize his own re-enactment of the march undertaken by Canadian soldiers in Sicily. A Whitehorse filmmaker, Max Fraser, agreed to go along to record the event.

Gregory enlisted Zuehlke as the trek’s historian after reading his book, Operation Husky: The Canadian Invasion of Sicily, July 10 - August 7, 1943. This was years before the march. While he didn’t mind being a historical consultant, Zuehlke was at first reluctant to join the marchers.

“I was thinking: ‘Well, I’ll be kind of tired of this thing by that time,’ ” he said.

In its initial stages, Operation Husky 2013 had ups and downs. At one point, it seemed Gregory had 100 people signed up. Then it appeared no one would join. Eventually, the project gelled. Caught up in the momentum, Zuehlke agreed to go along.

An avid cycler, backpacker and kayaker, he trained by doing walks of up to 20 kilometres along the Galloping Goose trail. His wife, author Frances Backhouse, eventually agreed to join her husband in Sicily.

The other trekkers were mostly middle-age folk. The youngest had just turned 40. The oldest was a 70-year-old who dropped out for several days due to heat exhaustion.

There were retired military officers, a priest and a bank executive. Each day, they’d walk 15 to 35 kilometres along country roads, often in hilly terrain, followed by an escort motorhome. At each town, their arrival was heralded by a Canadian pipes-and-drums band.

Sometimes, the marchers were joined by Sicilian Second World War re-enactors. The military re-enactment movement is especially big in Europe, Zuehlke said. “You go to Normandy, it’s nauseating in Normandy. There’s whole convoys, with period jeeps and trucks.”

Town officials had organized official welcomes for the trekkers. Nonetheless, Zuehlke wondered whether ordinary Sicilians would care about a gaggle of Canadians marching in the mid-day sun.

He needn’t have worried. Town streets were typically lined with hundreds of appreciative locals. Interestingly, many recognized Canadian soldiers as having been distinct from American or British military.

“They always said: ‘Canadese,’ ” Zuehlke recalled.

The most popular member of the Canadian contingent was Capt. Sheridan Atkinson, a 92-year-old veteran of Operation Husky. Atkinson didn’t do the march. But he was driven in to make eloquent speeches at various stops, including “marker ceremonies.”

For these, commemorative white stakes for each soldier were inserted in the ground near where they are believed to have fallen. Zuehlke was especially moved by one marker, upon which a Sicilian child had written: “You came from far away to fight in a war that wasn’t yours. And you lost your life for us.”

The culmination of the trip was a visit to Agira Canadian War Cemetery, in the centre of Sicily. It’s the final resting place for 490 of the 562 Canadian soldiers who died. For the event, they were joined by almost 1,000 Canadians and Italians. It ended with a ceremony in which one person standing beside each headstone answered a roll-call of the deceased.

Zuehlke has written extensively on Canadian military history, including his 11-book Canadian Battle series. The notion of remembering this country’s fallen soldiers is nothing new to him. But the Sicilian march gave the historian a fresh perspective.

“Now, I’m looking at remembrance as a very personal experience,” he said.