Penny Fox knew that she was adopted, and that her parents had paid $500 for her.

“I was a grey-market baby,” said Fox, who was born in Vancouver 69 years ago and quietly handed off to her parents at two days old. She was eventually legally adopted, but her mother wouldn’t tell her much more. The mystery of her origins tugged at her.

In 2018, her husband bought her an Ancestry DNA kit.

“I always thought they were just a big scam,” said Fox.

It wasn’t. The website immediately matched her with a biological first cousin. Days later she was sitting in a coffeeshop across from a woman who looked just like her. Family.

Home DNA kits have been popular Christmas gifts since 2012, when Ancestry launched the first do-it-yourself mail in kits. The consumer genomics’ market has boomed, reaching US$2.87 billion in 2022, pushed by the growing interest in family genealogy, ethnicity and genetic predispositions.

An estimated 30 million people worldwide have loaded their genetic profiles onto the popular sites, such as Ancestry, My Heritage and 23 and Me.

Some countries, such as France, strictly regulate their use to protect the privacy and rights of the individuals and prevent the unauthorized collection and use of genetic data. In Canada, consumers are protected by the Genetic Non-Discrimination Act, which prohibits insurers and employers from requesting DNA testing or results.

Since the emergence of forensic genealogy, consumer DNA kits have helped police solve decades-old cold cases, but the surprises they contain may not always be welcome.

Rob Whitley, an associate professor of psychiatry at Montreal’s McGill University, has studied the impact in depth.

“I found that I now have a cousin who lives on Vancouver Island. It’s been a great pleasure to discover this person,” Whitley said.

But not everyone is so lucky.

“We interviewed over 50 people who took a commercial DNA test, with the aim of learning more about their ethnicity,” he said. “They were looking at this as a fun, harmless process, but quickly realized it wasn’t, when they discovered their father was not their father.”

Unexpected genealogical discoveries can affect mental health, causing grief and trauma, said Whitley, especially an “NPE.”

In the lingo of recreational genetics, an NPE is a non-parental event. Non-parental events are so common that most sites provide resources connecting users to support groups, even though, as one NPE posted on the NPE fellowship website, “DNA ruined my life.”

“It’s a traumatic event from the click of a mouse, and you might need immediate counselling,” Whitley said.

There is profound shock, and difficult decision-making around confronting your family.

“It’s a Pandora’s box of ethical issues.”

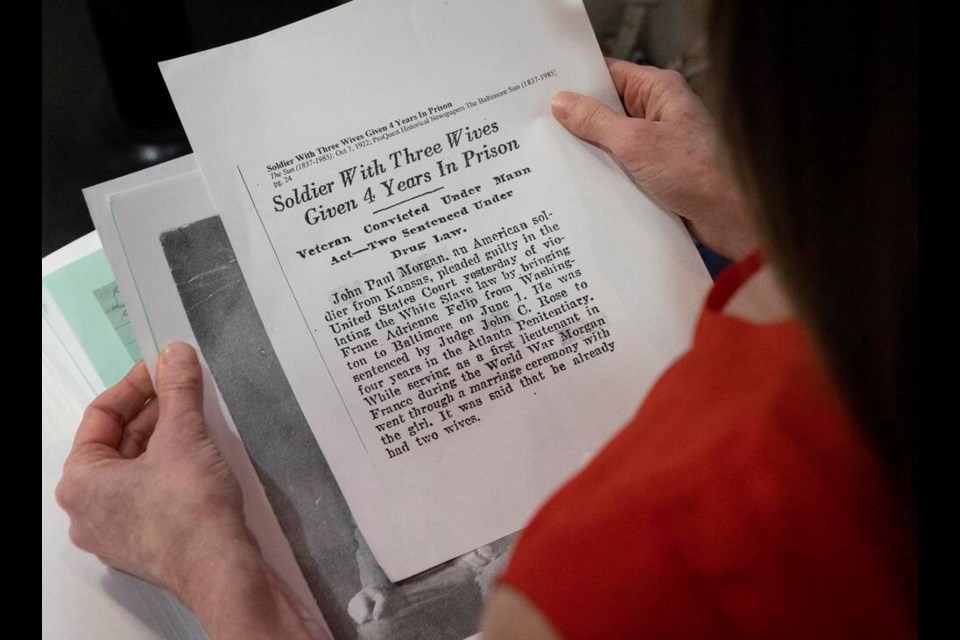

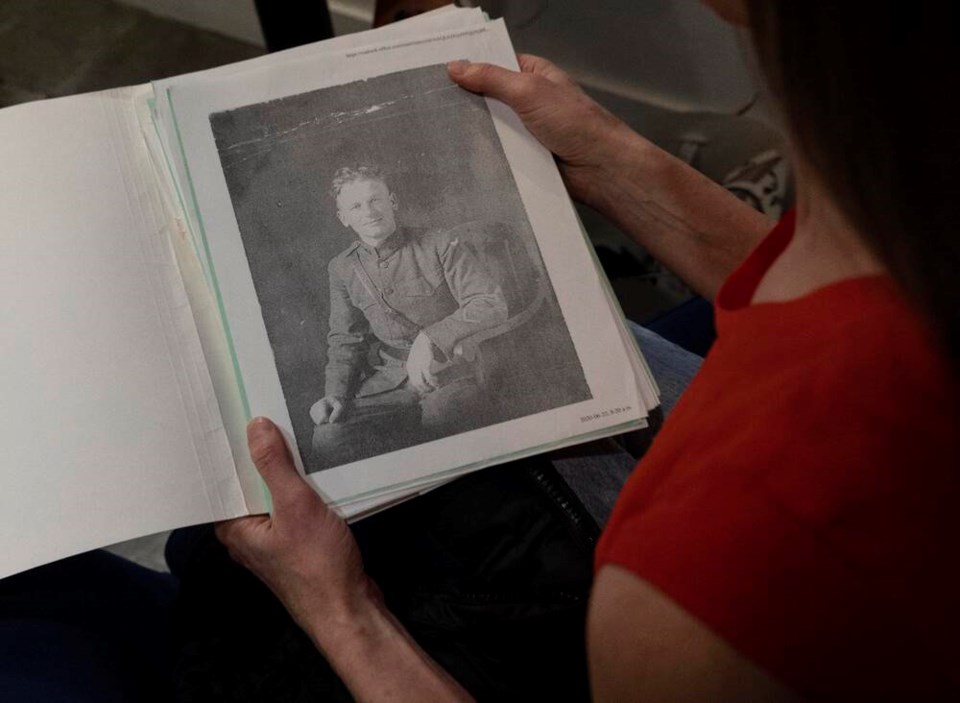

Suzanne Morgan, 54, a Vancouver public school teacher uncovered a complicated family history after doing a casual DNA test. Morgan had always been interested in genealogy, and her grandfather, John Paul Morgan, a former baseball player, who died when she was nine years old, was a bit of a mystery.

He didn’t talk much about his past except that he had been an orphan — and that he had played baseball in Baltimore with Babe Ruth. He was Canadian, but he had a southern drawl.

“It didn’t add up,” Morgan said.

After doing an at-home DNA kit in 2019 she got a hit. A first half-cousin on her father’s side — in California. The family story blew wide open.

“It was shocking, astounding, gobsmacking,” Morgan said.

It was also heartbreaking. Her grandfather was not an orphan nor was he Canadian.

“He had four sisters, two full sisters and two half-sisters,” Morgan said.

She learned that he had had grown up in Virginia, had a troubled childhood and had been sent to reform school.

“He lied by omission not telling us the full story of his life,” Morgan said. “He had played baseball with Babe Ruth at St. Mary’s Industrial School For Boys. He was a catcher, Babe was a pitcher.”

After his time in reform school, he played throughout the U.S. in the Industrial Leagues, but he wasn’t as lucky as his reform-school buddy, Ruth.

By the time he was 23 years old, he had three wives, and three children. He was caught, charged and jailed for a short period.

Around 1929 he came to Canada, where he played for a baseball team in Victoria, got married and kept his past life a secret.

Morgan learned that he had never contacted his four sisters, three wives and children again.

“They never knew what happened to him. It was devastating for them.”

Solving the mystery was healing, but it was also difficult, Morgan said. He had been a wonderful husband, father and grandfather to her family, but not to those he had left behind.

Crista Cowan, Ancestry’s Family History and DNA expert, said that these stories, especially around grandparents, aren’t uncommon. Ancestry had a list of support resources on their website, and she encourages people to be careful about how they approach newfound family.

Fox sought counselling before meeting her biological family.

“I was prepared for rejection or unkindness.”

She got the opposite: A family that fully embraced her.

“My loop is closed. I am at peace, now.”

— With research from Postmedia librarian Carolyn Soltau. Soltau is also a grandaughter of John Paul Morgan.