A bandage that can sense when a wound is becoming infected could make its way to your medicine cabinet from a laboratory at the University of Victoria.

The bandage, called GelDerm and pioneered by a UVic bioengineer, contains material that changes colour in reaction to chemical changes in a wound when an infection occurs. The material responds to shifts in the pH or acid levels of the wound.

When colour changes are subtle, perhaps at the start of an infection, they can be difficult to detect with the naked eye. Health-care professionals working after dark when patients are asleep might miss a change in colour even when it’s dramatic.

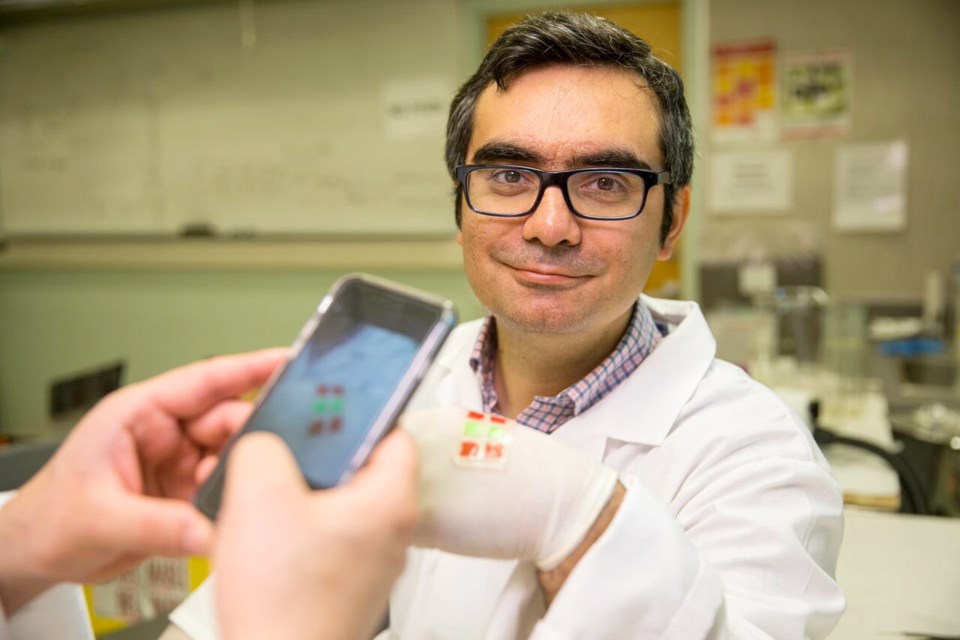

So bandage developer Mohsen Akbari, a professor in UVic’s department of mechanical engineering, with assistance from grad student, Bahram Mirani, has developed a smartphone app to detect subtle colour changes and spot infections when they start.

Akbari said the smartphone app will allow a patient to be monitored at home after a wound has been dressed.

The patient can take pictures of the bandage at intervals with a phone and upload them to a hospital where health-care providers can check the healing.

The material in the bandage is a gel substance made from algae. Similar materials are on the market for other uses.

So it’s cheap enough to be mass produced for the home.

“We don’t have any expensive material in the bandage,” Akbari said. “It is very cheap.”

In another innovation, the bandage material can contain antibiotics, to further reduce the chance of infection.

Unlike topical creams or powders, the antibiotic in the bandages can be time released to better attack any infection as it progresses.

But Akbari said the biggest innovation is the colour-changing feature that allows the wound to be monitored without removing the bandage.

Uncovering a wound can introduce bacteria. With Akbari’s bandage, health-care workers can be relieved of the task of regularly removing a bandage to take a swab of a wound to test for bacteria.

He expects a big application for the bandage will be the care of patients with diabetes. Cuts or injuries to these patients take a long time to heal, weeks or months. Diabetes also diminishes immune capacity.

So a new bandage that monitors for infection without disturbing the covered wound will be an advantage.

Akbari estimates the new bandage could be on the market in as little as five years.

His research was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Canadian Foundation of Innovation.

Other collaborators in his work include Dr. Aziz Ghahary of the University of British Columbia and Yu Shrike Zhang at the Harvard Medical School’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital.