WINNIPEG - The woman who is now Manitoba's children's advocate is criticizing how some social workers dealt with a young girl who was beaten to death after she was handed back to her violent mother.

Darlene MacDonald told an inquiry into Phoenix Sinclair's death that social workers should have dug into the family's long history of troubles before closing the girl's file. She also said they should have made a point of seeing the five-year-old instead of accepting her mother's word that everything was fine.

The entire handling of Phoenix's case — from her birth in April 2000 to her violent death five years later — amounted to a series of crisis interventions by different people, instead of having one social worker help the family over the long term, MacDonald suggested.

"It looked like every crisis that had come up, it was handled and dealt with, and then just closed off, and wasn't transferred long term to family services," MacDonald said Tuesday.

"I don't know why that would be."

MacDonald was a program manager at Winnipeg Child and Family Services during most of Phoenix's short life. Later on, MacDonald would be appointed the agency's chief executive officer and, in 2011, named children's advocate — an independent adviser to the Manitoba government who speaks on behalf of children in care.

MacDonald told the inquiry what Phoenix and her parents needed was someone to work with them over the long haul.

"Social work is all about relationship-building and I think it's really important that one social worker get to know the family, work with the family."

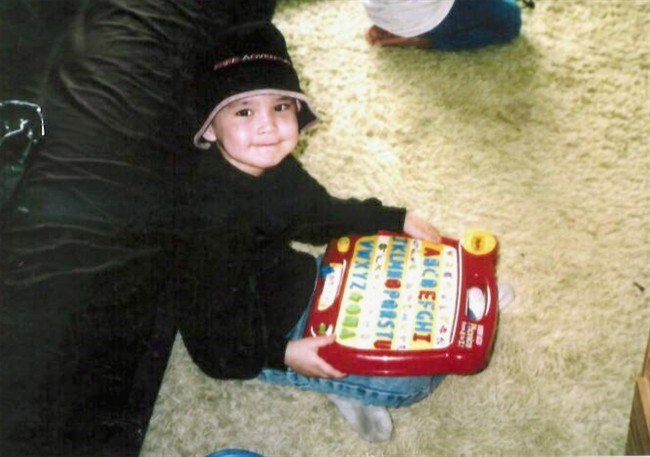

The inquiry has already heard that Phoenix continually fell through the cracks of child welfare. She was taken from her parents — Samantha Kematch and Steve Sinclair — days after her birth because the couple had violent histories and were unprepared to care for her. Months later, Phoenix was returned to the couple with virtually no supervision.

Social workers were sometimes unaware of who was taking care of her — usually family friends or relatives for days or weeks at a time. They also missed that Karl McKay, a boyfriend Kematch started living with in 2004, had a long history of domestic violence that including beating one former girlfriend with the leg from a bathroom sink.

The child's case was reopened and closed on several occasions, always with a different social worker. She was seized from Sinclair's home in 2003 after a day-long drinking party, but was back with him within months.

An internal agency review of the case, done in 2006 but kept secret until the inquiry, concluded that "from October 2000 to the last contact with this family, actual service was almost non-existent.''

The final chance to save the young girl came in March 2005 when two social workers responded to an anonymous call that Kematch was abusing Phoenix. They visited Kematch's apartment. She kept the workers in the hallway, saying she had a visitor, and said she had simply yelled at Phoenix. The workers decided all was well, left and closed the file.

In June, Phoenix was beaten to death by Kematch and McKay on the concrete basement floor of the couple's home on the Fisher River reserve, north of Winnipeg. The two were convicted of first-degree murder. Their trial was told they frequently confined and abused the girl, sometimes shooting her with a BB gun and forcing her to eat her own vomit.

MacDonald said Tuesday the workers should have seen Phoenix before closing her case.

"If somebody called and said a child was at risk, then I do believe the child needs to be seen."

But under cross-examination by Kris Saxberg, a lawyer representing regional child welfare authorities, MacDonald admitted the requirement was not a firm rule at the time.

"Would you agree with me that the workers that were dealing with that matter had a discretionary call ... and that there was no specific standard that required them to see Phoenix?" Saxberg asked.

"The child was the subject of the (call). The child should have been seen," MacDonald replied.

"I know that that's your opinion. The question was more specific about whether there was a specific rule in place ... was there?" Saxberg continued.

"Not that I'm aware of," MacDonald answered.

None of the social workers involved in Phoenix's life was ever disciplined. Some have retired, one has died, but most continue to work in child welfare. The social workers union, as well as some witnesses who have testified at the inquiry, have pointed to high caseloads and a system struggling to cope with structural changes that include the transfer of many files to new aboriginal-run agencies.

Since Phoenix's death, the Manitoba government has pumped more money into child welfare, paying for 230 new positions and 5,000 new foster care and emergency shelter spaces. The government has also passed laws to ensure, among other things, that children are seen before their files are closed. Yet the number of children in care continues to increase.

In her role as children's advocate, MacDonald issued a report last September that said many concerns her predecessor raised in 2006 had still not been addressed, including an outdated central database and an incomplete child abuse registry.

And the tragedies have not stopped since Phoenix's death.

In 2007, two-year-old Gage Guimond was given to his great-aunt, Shirley Guimond, despite the fact she had a criminal record. The boy was beaten frequently and died after falling down stairs.

In 2008, 13-month-old Cameron Ouskan died of injuries after being placed in the foster care of Roderick Blacksmith, who faces a charge of second-degree murder.

In 2009, 21-month-old Jaylene Redhead was smothered by her mother, Nicole, at a treatment centre while under child welfare supervision.

In 2010, then-children's advocate Bonnie Kocsis said in a private report submitted to a legislature budget committee that child welfare was "in a state of chaos." Kocsis cited a growing number of kids in care, high staff turnover among social workers and mistrust among foster parents.