Two Vancouver Island-Africa stories, two discouraging sequels.

The first is the seemingly never-ending immigration drama encountered by Saltspring Island’s Jennifer Lannan.

Lannan’s tale has played out in this space for the past couple of years. In 2008, she married a Nigerian man she had met in South Korea. After a 2010 interview with Canadian immigration authorities in Ghana led them to believe his move here would be approved, they felt free to start a family.

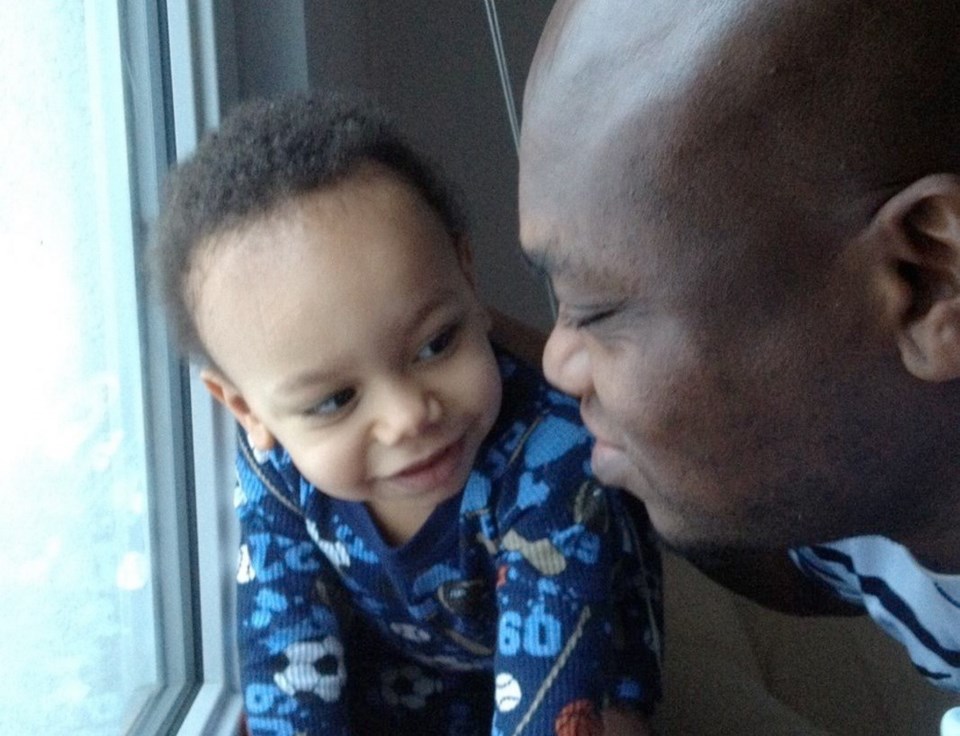

Except when baby Gerard was born on Saltspring Island in February 2011, dad John Emekoba was still stuck in Africa, bound in red tape.

To make a long story a little less long, it took until this past spring for Lannan, with her member of Parliament, Elizabeth May, at her side, to win an immigration appeal hearing in Vancouver. Hurray! Ordeal over.

Except, eight months later, the process is still dragging on like an NHL lockout. Emekoba remains stranded in Africa, where the Canadian visa office appears as overwhelmed as it is impervious to pressure from abroad. In September, the couple learned the process had taken so long that Emekoba’s original forms had become outdated and he would have to fill out new ones. After that, a deathly silence.

“It’s ridiculous,” Lannan said Monday. Her lawyer is powerless. So is May’s office. Even the Citizenship and Immigration Canada help centre in Ottawa tells Lannan that it can do nothing to light a fire under the processing office in Ghana.

Alas, stories of systemic constipation are nothing new for Canada’s overseas immigration offices. Ottawa has cut by more than half a backlog of 640,000 skilled-worker applications, but critics say applicants in other categories, such as the family-reunification class, have been allowed to languish.

“I’m really frustrated to see [Immigration Minister] Jason Kenney stand up and say they’re reforming the system,” Lannan says. Sure they are, just not if you’re an ordinary family trying to have an ordinary family life.

“It’s amazing to me that Conrad Black can apply from prison for a visa and that’s OK … yet someone who’s never been arrested can’t come to Canada,” says the 30-year-old Lannan, who works at Salt Spring Coffee.

Emekoba was even denied a visitor’s permit, the authorities reasoning that once here he might never leave. Never mind that the same authorities have already said he can immigrate. Never mind that his business, buying fabric for the Nigerian garment industry, would regularly require him to leave Canada for Eastern Europe and Africa.

Mother and son joined Dad in Poland on Boxing Day, got to be a family for two weeks. “There’s no question about the success of our marriage once it gets a chance to flourish,” Lannan says.

Gerard, two years old next month, found the subsequent separation hard, though.

“He has been crying for his dad every day since we left.”

The second unhappy African sequel is relayed by Saanich physician Lorraine Irvine.

Beginning in 1996, Irvine has spent several months each year volunteering at the Salvation Army-run Howard Hospital in rural Zimbabwe. It’s the kind of place that’s always short of everything but compassion for the hundreds of patients who line up outside each day.

Last August, Irvine was preparing for another four-month stint when word came that Howard’s chief medical officer, Canadian Paul Thistle, had been abruptly fired and ordered to leave the country after a run-in with the church’s hierarchy in Harare.

This shocked those who regard Thistle as a saintly figure who 18 years ago abandoned a lucrative career as a Canadian surgeon in favour of 70-hour weeks caring for the poor. His supporters included the Vancouver Island Scottish Country Dancers (they regularly bought goats for orphans and paid poor Zimbabweans’ school fees) and volunteers at Esquimalt’s Compassionate Resource Warehouse, from whence medical supplies were channelled to Howard.

Irvine, who cancelled her 2012 trip, was among the many who came to Thistle’s defence, calling on the Salvation Army to intervene with its Zimbabwean operation. Six months later, no such luck. Thistle, ignoring the order to leave the country, has moved to an interfaith hospital elsewhere in Zimbabwe.

The reports from Irvine’s friends at Howard are grim. Being deprived of its only surgeon was bad enough, but when the hospital lost Thistle, it lost much more than that.