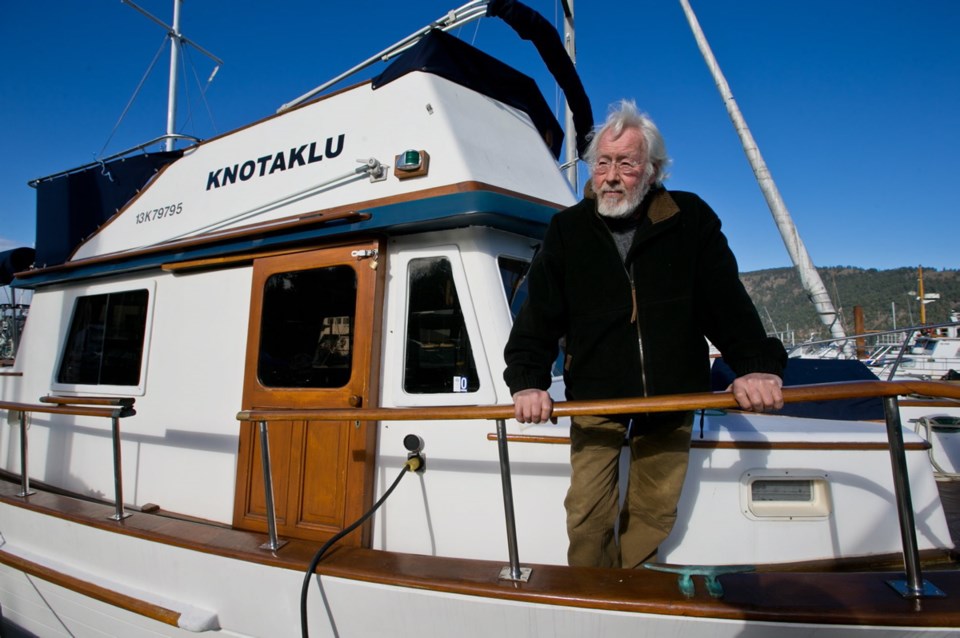

George Weeks thought he had hit bottom when his 42-foot liveaboard boat sank in Cowichan Bay.

George Weeks thought he had hit bottom when his 42-foot liveaboard boat sank in Cowichan Bay.

The six Chinese tourists on board got off safely, but the 76-year-old Weeks lost everything he owned when the Fisherboy II, a converted west coast troller, got hung up on a couple of submerged logs and went over last June.

“I didn’t have anything except the clothes I was wearing.” No insurance, either.

Then the community came to his rescue.

“Everybody in the bay helped me.” A Let’s Keep George Afloat fundraiser at the pub helped him buy a replacement, a 32-footer. He’s living in a friend’s boat at the moment while replacing his new vessel’s gas-guzzling Chrysler V-8 with a six-cylinder Nissan diesel.

Happy ending, right?

Not quite.

Weeks may be afloat again, but he also feels adrift, as do other liveaboard and floathome residents who worry they are being pushed out of picturesque Cowichan Bay.

Not to fear, say local authorities. Government is trying to accommodate, not evict, the floating villagers, but they’ll have to abide by regulations.

Over-regulation is more like it, says Weeks. It’s not just in Cowichan Bay, either. The liveaboard lifestyle romanticized in coastal classics like The Curve Of Time and Spilsbury’s Coast is disappearing as old gypsies in old boats find themselves in conflict with officialdom.

“There’s nowhere to go,” Weeks says.

Weeks has lived on boats since 1963, been in and out of Cowichan Bay for the past 20 years. Owning a nautical mobile home gave him the freedom to go where the jobs were: shipyards in Shearwater and Prince Rupert, the steam plant at Crofton, watchman in logging camps, fisheries patrols in Haida Gwaii. Once, with $41 to his name, he pulled into Ocean Falls, went to the bar and was hired as a stationary engineer in the paper mill. “I always had work.”

He’s retired now, typical of liveaboard residents. “Most everybody on the water is over 60 and there are a whole mess over 80.” They find it hard to insure their old wooden boats these days, and hard to sell them, too.

The exact numbers are hard to pin down in Cowichan Bay: two dozen floathomes in a half dozen marinas, and perhaps the same number of liveaboards, including a few that drifted down from Maple Bay recently after the introduction of a marine zoning bylaw there.

It’s a plan to introduce a similar bylaw to Cowichan Bay that has emotions running high. Lori Iannidinardo, the area’s elected representative on the Cowichan Valley Regional District board, says the bylaw would actually bring legal protection to the floating homes, which have been tolerated despite a lack of any provision for them in existing rules.

In fact, the new Official Community Plan explicitly recognizes floathomes add to the ramshackle charm of Cowichan Bay, where such local delights as the True Grain Bakery and Hilary’s Cheese draw tourists to the funkiest half-kilometre strip on Vancouver Island. In 2009, the village was designated North America’s first Cittaslow community, one that is dedicated to preserving a quality of life through design. Conservation groups have made a concerted effort to roll back the clock, clean up a bay so polluted by industrial activity and run-off that there hasn’t been commercial shellfish harvesting since the 1970s.

Part of the cleanup means getting a handle on wastewater from the liveaboards, says Iannidinardo. Floating residents have to abide by rules, just like other homeowners. “It’s no longer the Wild West.”

Liveaboarders bridle at the suggestion they are being irresponsible, reply that they either dispose of waste in a proper manner or have been barred from doing so. A debate involving issues like sewage, greywater, pumping stations and building inspections has gone on for months, and will go on for a few months more as the bylaw process works itself out. The next big public meeting is scheduled for Feb. 25.

Weeks, who doesn’t think much good happens when government gets involved, fears being sunk — again — by expensive solutions to a problem he doesn’t think really exists. He has also decided to bow out of an acrimonious process in which he has little faith. Others can go to the meetings.

“I’m going to sit here until they tell me I can’t live here, then I’m going to move farther up the coast.”

But where?

This is a corrected version of an earlier story.