Asked what Canadians might not appreciate about Canada, Olga Voyloshnikova pauses, then replies with a practical observation: “the roads.”

Really. They’re well-paved, unbroken and you can ride your bike without taking a header. Olga also says Canadian police are better than those back in Russia — “not tricking people.”

Other recent arrivals have their own answers. Irish-born Marita Middleton thrills at the great expanse of a country just waiting to be explored, while Thai native Mae Yoskul talks of the chance to make a decent living.

When Romania’s Christian Paduraru speaks of “Canadian values” and “peace,” and Cuba’s Marco Bequer and Ana Maria Toledo toss around words like “freedom,” “prosperity” and “opportunity” — terms that in other mouths might sound like sloganeering — it’s a little humbling.

They were among 60 new Canadians who got their citizenship in Victoria on July 1 — an always-moving event in a nation of immigrants, a country where most of our grandparents spoke with an accent from somewhere else.

It was a cheerful affair — clicking cameras, red-and-white bouquets, uniforms, flag-clutching children — in the swankiness of Government House, with its chandeliers, stained glass and a full-length portrait of our Queen (who also has an accent) in front of the Canadian flag.

Alas, not everyone had a happy ending to their immigration story Monday.

On Saltspring Island, Jennifer Lannan celebrated Canada Day by taking her 2 1Ú2-year-old son, Gerard, to the cake-cutting in Ganges.

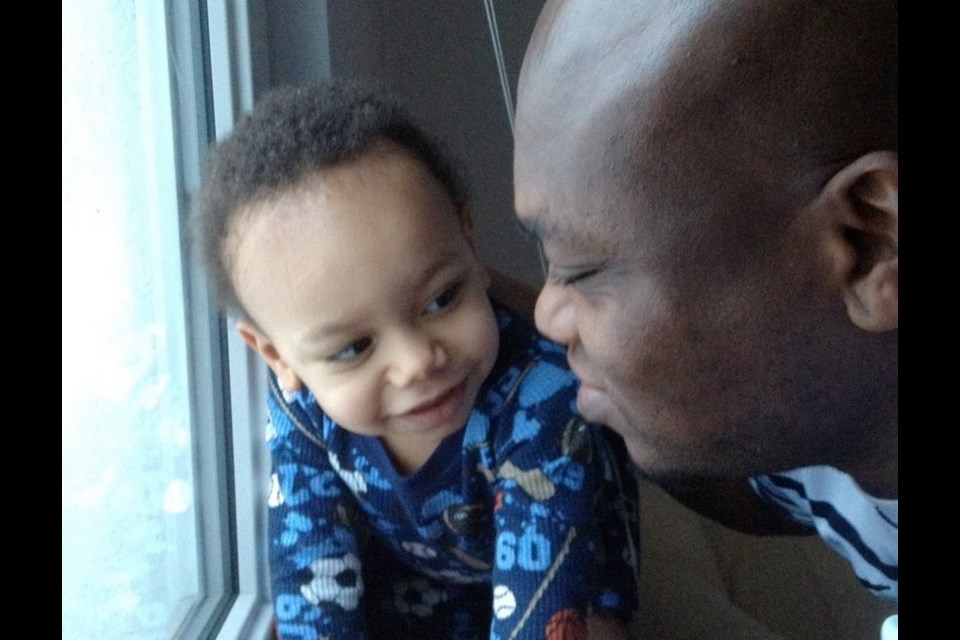

You might remember Lannan’s story from previous columns: she met a Nigerian man in South Korea, married him in 2008 and, after a 2010 interview with Canadian immigration authorities in Ghana led them to believe his move here would be approved, got pregnant. Except when little Gerard was born on Saltspring in February 2011, his father, Johnson Emekoba, was still waiting for the green light to Canada.

Emekoba is still waiting, trapped in the world’s slowest game of bureaucratic ping-pong, his application caught up in an immigration system that appears totally overwhelmed.

Even after MP Elizabeth May helped the family win a May 2012 immigration appeal hearing, nothing moved. May and her constituency staff are exasperated. So, understandably, is Lannan, who finds herself living as a single mom, her child only seeing his father via daily conversations on Skype. “The appeal last year was allowed on humanitarian and compassionate grounds in light of Gerard having a financially stable, grounded home with two parents,” Lannan says. “That things have gone on like this ought to be considered criminal.”

The latest chapter involves a letter mailed from Canada’s visa office in Ghana in February, asking Emekoba for info from South Korea, where he conducted an export business. Unfortunately, the letter never arrived. Emekoba and Lannan didn’t know about the request until an e-mail arrived in mid-May. (Don’t even bother asking why the request wasn’t e-mailed in the first place.) So, Canada Day saw Emekoba take a 15-hour bus ride from Aba, Nigeria, to the capital, Abuja, where he hopes to get what he needs from the South Korean consulate. At this rate, Victoria will get sewage treatment before Emekoba gets to hold his son again.

It would be bad enough if this story were an anomaly, but it isn’t. May’s constituency office is buried in immigration complaints. So is Victoria MP Murray Rankin’s. “It’s the biggest single issue, without a doubt,” Rankin said after Monday’s ceremony.

It’s getting worse, too, as federal service cuts leave the remaining bureaucrats overwhelmed. “They’re now telling people ‘We can’t help you, call your member of Parliament,” Rankin says. Citizenship and Immigration Canada closed 19 offices last year, including those in Victoria and Nanaimo.

In March, Immigration Minister Jason Kenney announced the wait list of would-be newcomers had been reduced 40 per cent in a year, falling to 616,271 from just over a million. The reduction was achieved largely by throwing out 280,000 applications that had been languishing in the system for four years or more.

Ottawa also placed a moratorium on applications from investors and entrepreneurs, and from the parents and grandparents of immigrants. (It plans to accept a limited number of applicants under the family-reunification program next year).

It’s still an excruciatingly slow process. Once a typical citizenship application has been acknowledged by Ottawa, it takes 23 months on average to process, six months longer than was the case in 2005.

So, to those who took their citizenship on Canada Day, congratulations. Some of us are lucky enough to be born Canadian, but others have to work at it for a long, long time.