Twenty minutes before sunrise, veterinarian Adam Hering is behind the wheel of his blue Toyota Highlander searching for an elusive deer with a white collar in south Oak Bay.

It’s a cold, crisp, late October morning and the last time Hering will be able to give the doe a booster of an immunocontraceptive vaccine that will prevent her from having fawns.

Hering is the lead wildlife veterinarian of the Oak Bay Deer Project, a first-of-a kind study that is attempting to reduce the number of wild deer in the municipality. Oak Bay, the province and a citizen-led anti-cull group called the Urban Wildlife Stewardship Society are working together on this deer birth-control initiative.

Hering drives along the dark roads, scanning left and right for the doe. His safety vest and dart projector — a modified rifle capable of firing vaccine-laden darts — are at the ready in the back of his SUV.

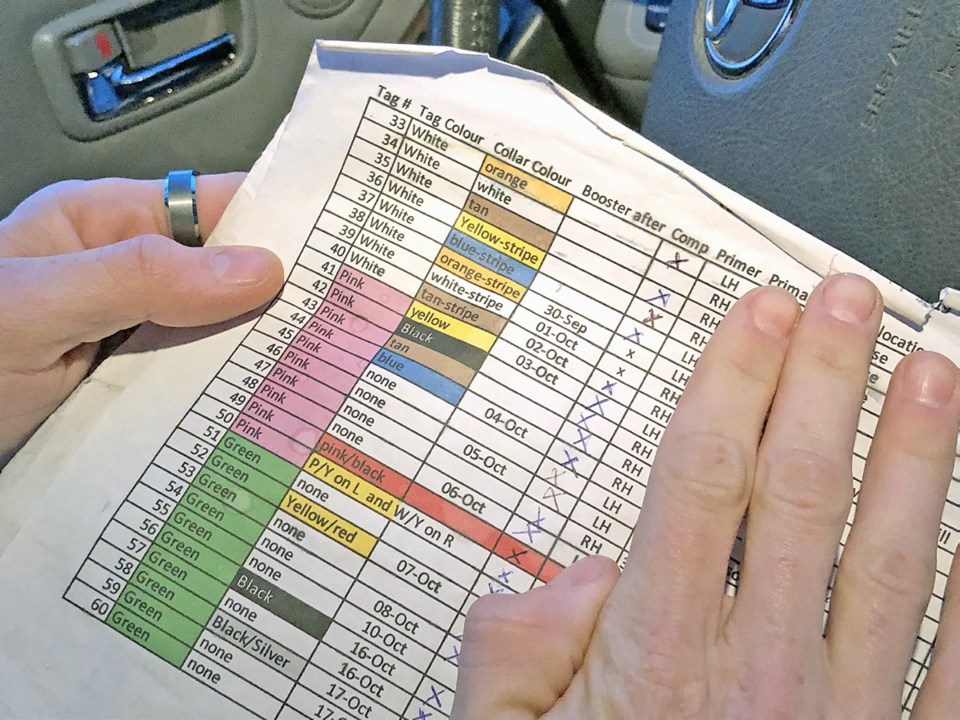

Hering also has the medical records of the 60 deer that have already been inoculated this fall. And, as a precaution, he has made a call to Oak Bay police to let them know he’s in the neighbourhood, in case someone calls 911 to report a man with a gun in their backyard.

Hering and dozens of volunteers began administering the immunocontraceptive in September. From 6 a.m. to 1 p.m. most days, they searched for deer on both public and private land. When they found a doe, Hering darted her with a sedative.

“We took blood and hair samples and skin biopsies and put on ear tags and collars. Then we injected the primer dose of the vaccine by hand,” said Hering. “Two to six weeks later, we try to give them a booster.

“The booster vaccine is loaded directly into the dart, so we just have to dart the doe, not sedate her.”

The doe with a white collar is one of three animals that were tagged, but did not receive their booster shots before this phase of the project ended on Oct. 31.

“The fact we’ve got every one but three is really surprising and impressive and really great,” said Hering.

The deer-management project began in 2017 when 20 deer were outfitted with GPS tracking collars, and 40 motion-sensor cameras were installed along trails in Oak Bay to photograph wandering deer.

The cameras and collars gave the researchers an idea of where the deer spend their time and how far they range. In 2018, the Oak Bay deer population was estimated at 100 to 120. Hering thinks it has increased since then.

“We have vaccinated 60 does and there are another 17 with GPS collars. That’s 77 does,” said Hering. “For sure if you include this year’s fawn crop, it’s higher than 120.”Although there are a lot of deer, many of them are not in great condition and are quite thin, said the wildlife vet, who doesn’t know why.

“There’s tons of forage around and they should be able to eat to their heart’s content. I don’t know which plants people have in their gardens are good options for the animals. I see them eating acorns quite frequently,” Hering said.

So far, four animals outfitted with GPS collars have died. Hering completed post-mortems on those deer and found three of the four animals were thin and malnourished.

“They had full stomachs, full of food, but obviously whatever they were eating wasn’t nutritious. All of them had diarrhea. Maybe they’re eating foods that are too rich and that’s giving them diarrhea, or they’re eating food that’s not nutritious or that there’s some infectious agent we haven’t managed to find,” Hering said.

“Maybe people are using certain fertilizers that aren’t good for them.”

The researchers have talked about investing more resources to try to find out what’s making the deer sick, but they need to figure out what they can test and who can do the testing.

“It’s not really the kind of thing you can just send off for toxicology. You have to narrow it down. It’s not simple or straightforward and you need the money to do that testing.”

The fourth deer, which died on a little peninsula near the Royal Victoria Yacht Club, had an abdominal infection, maybe from a puncture wound. People had seen her swimming the day before she died. She was in really poor condition, he said.

Although deer can live into their teens, Hering hasn’t examined any that were older than six. Deer age can be determined through teeth.

Wildlife work is always controversial, but this project is less controversial than the cull in 2015 that killed 11 deer in two weeks, Hering said.

“It’s a solution that everyone can feel really good about. Almost across the board, when I’m out, people are happy to see me — except for the fact that some people get scared when they see me with a gun, if they don’t know about the project,” Hering said.

“The cull was really divisive and this is a feel-good option where not many people are opposed to what we’re doing. In a lot of cases, this is going to be good for many of the deer. Without the stress of pregnancy and lactation, I think a lot of them will be in better shape.”

The hope is that the deer will have a much lower reproductive rate, resulting in a smaller, healthier population, he said.

Getting permission this year to go into people’s yards was very helpful, said Hering. Oak Bay residents eagerly registered their properties to allow Hering and the volunteers to look for deer — 150 signed up in the first 36 hours. Often, he would invite them to come and watch him and the volunteers work.

“This is a great example of population reduction, but doing it in a way that people are comfortable with and feel good about. The community engagement has been over the top. There are thousands of hours of community volunteer work that has gone into this project.”

The project also gave Camosun College and University of Victoria students an opportunity to volunteer and learn about animal handling, Hering said.

“For a lot of these students, who might want to be a wildlife biologist or were interested in getting into vet school, this was a really unique opportunity. It’s not that common that people who are wildlife biologists get to have a veterinarian standing right over their shoulder, teaching them and guiding them through something like taking a blood sample,” Hering said.

Some people want the deer gone. But Hering’s not one of them.

“I think it’s good for us to have a connection to wildlife in town.”

The vaccine is only effective for one year, so the deer will need booster vaccines next year and the year after.

“There are longer-term vaccines that have been used in research settings and it’s definitely a priority for us to try and get one. I think the future progress of the project needs to be getting our hands on a longer-term, high-quality vaccine that we know will work.”