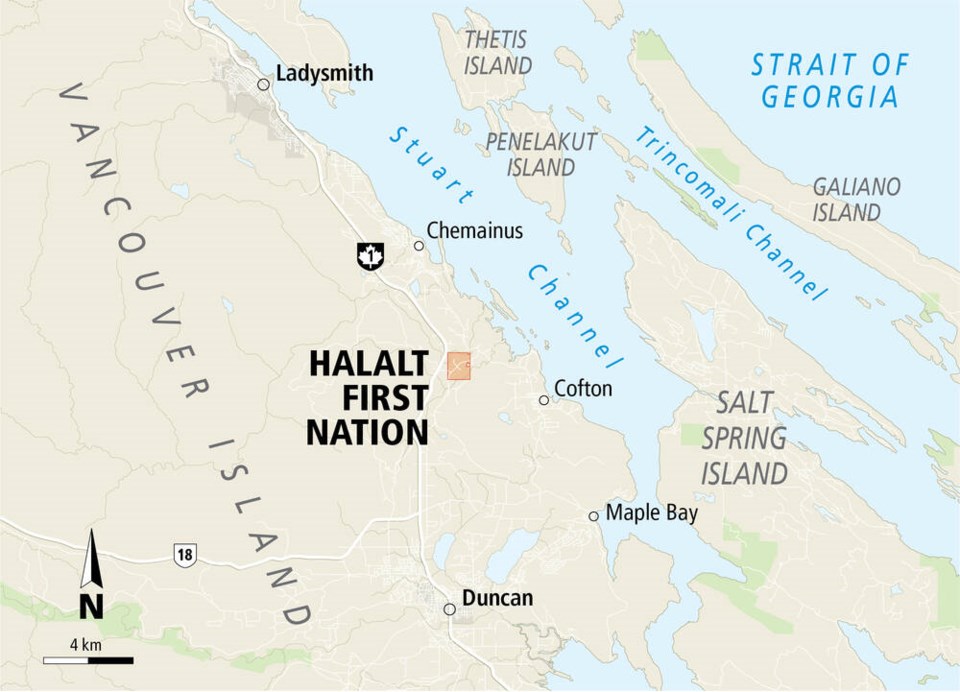

The Halalt First Nation near Chemainus is seeking the return of land taken from its reserve for the E&N railway in the early 1900s.

It earlier went to the Supreme Court of B.C. asking for land taken for the now closed railway. That suit remains active.

The nation is now considering the implications of Island corridor announcements on Tuesday by the federal and provincial governments.

They said that the Snaw-Naw-As First Nation at Nanoose is getting back 10 acres of Island corridor land running through its reserve and the province is putting in $18 million for consultation.

Vancouver Island residents were waiting to hear whether a proposed modern railway system would be backed by senior governments or if it might be used instead as a trail.

Instead, Erika Richards, lawyer for the Halalt Nation, said the governments “did not provide the kind of certainty or a clear response that Halalt was looking for.”

Minister of Transportation and Infrastructure Rob Fleming said the province and federal government are committed to work with First Nations to develop a shared vision and “will respect reversion of the reserved lands as part of the process.” He said the government recognizes how important the corridor is and “we would like to see it preserved as much as possible.”

Richards said it is not clear how those two statements are intended to work together.

Halalt First Nation is disappointed at the lack of a clear announcement about what would be happening going forward.

“They have effectively delayed the decision.”

The band was not adequately consulted as the government is constitutionally obliged to do and it does welcome true consultation, Richards said.

She said the Halalt First Nation will look at whether there are terms and conditions attached to reversion of lands.

And while the issue right now is about reserve lands, the corridor runs beyond the reserve and through traditional Halalt territories. Those lands have since been sold to private owners and the nation will not be able to get them back, she said.

The E&N railway has not carried passengers since 2011 because of the poor condition of the tracks. The line has largely been unused.

It has been more than 100 years since the railway was originally set up and First Nations feel its impacts today.

“The Halalt First Nation was absolutely affected by the railway. It cuts their reserve in half,” Richards said.

The original placement of the railway corridor through the reserve was done unlawfully, without the authority required by the legislation of the time, she said. It was constructed without the nation’s consent.

Within the reserve the corridor runs from the southwest corner of the reserve to the northeast corner, she said.

The corridor is causing flooding on the northern side of the reserve, Richards said.

It was built on a raised embankment and the entire reserve is on a flood plain. The embankment functions as a dyke, trapping water from the Chemainus River on the reserve, she said.

That prohibits water from spreading out across the rest of the floodplain as it would do if not blocked.

As waters rise during extreme weather, band members have been evacuated from their homes. This happened in February 2020 and November 2021 during the atmospheric river event, Richards said. People lost homes and their belongings, she said.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]