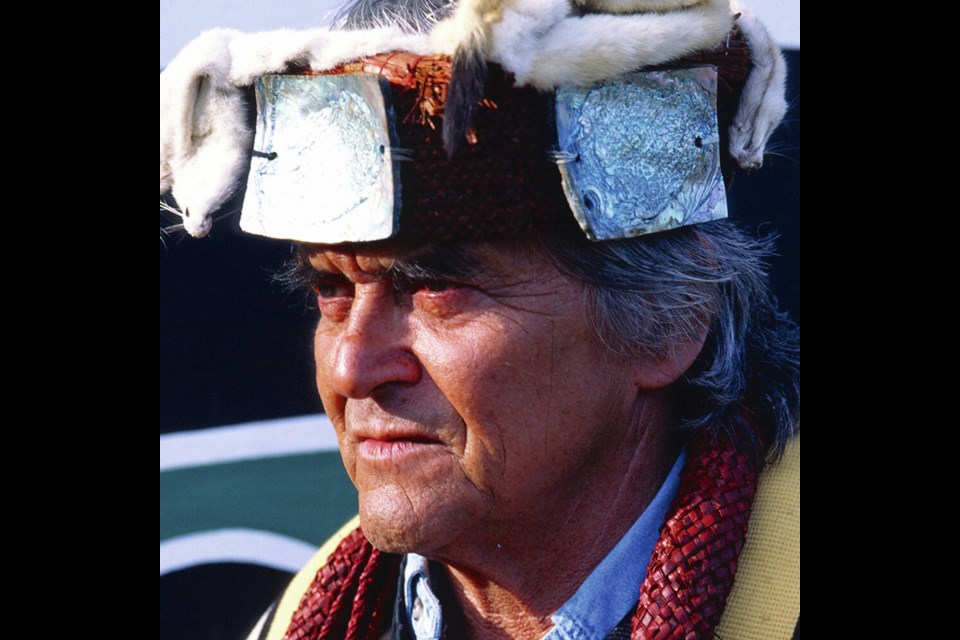

Bill Cranmer, a respected and influential leader among B.C. First Nations for decades, died Wednesday at his Alert Bay home on Cormorant Island. Known by the traditional name T̓łaḵwagila, he was 85.

Active until recently, Cranmer was a life-long defender and advocate of ‘Namgis First Nation culture, heritage and language. He opposed net pen fish farms, travelled to Ottawa to lobby for benefits for the nation and served as chief councillor on the nation’s council.

He played a critical role in repatriation of important masks and other items to the nation where they now reside in the U’Mista Cultural Centre on Cormorant Island.

Cranmer saw the benefit of expanding and diversifying the nation’s economy to provide opportunities for band members. The nation developed a partnership with Orca Sand and Gravel near Port McNeill and established the Kuterra fish farm where Atlantic salmon are raised in above-ground tanks under another operator.

Cranmer was a hereditary chief of the ‘Namgis nation, one of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples. Their traditional territory runs from Comox to the north end of Vancouver Island and includes nearby islands.

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs said Thursday that he had a “tremendous sense of admiration and respect” for Cranmer’s leadership, “particularly his expertise and hard work on preserving the culture and language for the people of his community and nation, and the amazing work they did on restoring the museum.”

B.C. Premier David Eby issued a statement saying, “We are deeply saddened by the passing of T̓łaḵwagila, Chief Bill Cranmer.

“His contributions to ‘Namgis Nation and Indigenous culture are immeasurable and will never be forgotten. We ask all British Columbians to remember T̓łaḵwagila for his impact and long-lasting contributions to Indigenous culture in B.C. and Canada”

Cranmer was honoured with the B.C. Reconciliation Award in 2022, recognizing his involvement in many organizations, including serving several terms on the executive board of the Native Brotherhood of B.C. and working with the First Nations Health Authority.

In a 1980 speech at the opening of the U’mista Cultural Centre, which houses much of the reclaimed potlatch items, he said, “It’s important to know your past if you are going to fight for your future.”

Nuu-Chah-Nulth Tribal Council president Judith Sayers, who worked with Cranmer, said he was outspoken on many issues, including the need to protect wild salmon fisheries.

She said Cranmer’s style was to approach problems by asking the parties involved: “How can we resolve it? What we can do?”

“That was just his way of getting business done. He was courteous. He was respectful. But he was very strong and dedicated to what he was trying to achieve for the people.”

Sayers said Cranmer was an “awesome dancer” in the Big House who was well-known for his knowledge of traditions and protocol.

The Cranmer name is particularly meaningful among B.C. First Nations. In December 1921, Chief Dan Cranmer, Bill’s father, staged a potlatch ceremony on Village Island. Officials swooped in to arrest participants and confiscated more than 300 items, including masks and rattles.

Cranmer dedicated countless hours to ensuring the repatriation of items that had ended up in public and private collections in North America and as far afield as Paris, France. Most have been returned.

The effect of the seizure in 1921 was dramatic. “What they did was stop our ability to pass on our history,” Cranmer told Times Colonist columnist Jack Knox in 2021.

The Potlatch Collection is “priceless,” he said. “It represents all the suffering our old people went through in the potlatch prohibition, the fight they went through to keep our history alive.”

Government actions against the potlatch represented what happened to the Kwak’wala-speaking people, he said. “We were the last people to be fighting against the potlatch prohibition and other things in the Indian Act.”

‘Namgis First Nation Chief Councillor Victor Isaac was 19 years old when he first joined the nation’s council, then led by Cranmer. “He’s been very influential in the whole community for years and years,” he said.

Many people looked up to Cranmer as a role model, admiring his intelligence, business savvy, and cultural knowledge, Isaac said.

Dr. Patrick Slobodian, who moved to Alert Bay with his family in the 1980s and became a close friend of Cranmer’s, described him as an “exceedingly dignified man. Having said that, he always had a little twinkle in his eye.”

Cranmer had a generous spirit, was firm and clear, and was a calm and open person and top-notch communicator, said Slobodian, who was adopted into Cranmer’s family.

Lisanne Granger, Cranmer’s partner, said he attended Indian day school but not residential school. He joined the Canadian air force working on electronics, and worked on a radar line in Alberta.

Cranmer returned home in the late 1970s and served as chief councillor for the nation for about four decades. He established Cormorant Island Services, specializing in marine electronics, and ran Bill’s Pool Hall, which served food.

He travelled to Toronto to officially welcome Nelson Mandela to Canada and greeted American talk show host Oprah Winfrey when she visited Alert Bay.

Cranmer was chair of the board of the U’Mista Cultural Centre from its inception in 1980 to the present.

Cranmer is survived by four children from previous relationships, Tracy Cranmer, Paula Cranmer-Underhill, Tyler Cranmer and Eli Cranmer, as well as five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

A funeral is planned for Sunday at Alert Bay in the ‘Namgis Big House.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]