A facial recognition system for grizzly bears could usher in a new wave of celebrity animals that scientists and the public could follow through their lifetimes.

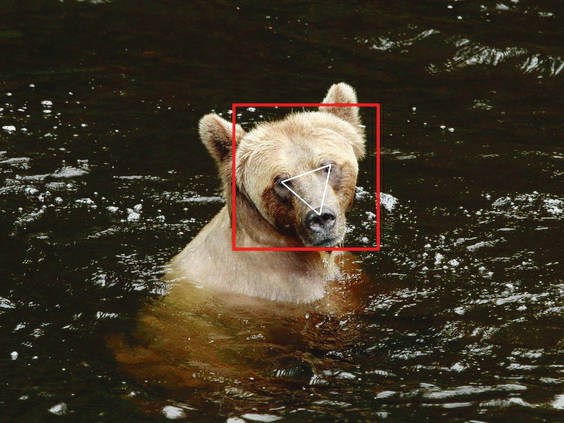

Biologists at the University of Victoria have teamed up with software experts to create an artificial intelligence (AI) that can recognize individual bears even though they don’t have much in the way of identifiable facial features.

“Learning about individual animals and their life stories can have really positive effects on public engagement and really help with conservation efforts,” said lead author Melanie Clapham.

Identifying and naming southern resident killer whales, such as new mother J35 Talequah, inspires deep public affection and concern for their wellbeing.

Grizzly bears live about 20 to 25 years in the wild, but few people outside the scientific community know much about the lives of individual bears, with rare exceptions.

A handful of celebrity bears in accessible areas — such as Banff National Park’s Split Lip and The Boss — do draw fans keen to spot them, so Clapham plans to protect the locations of her subjects to avoid human interference.

Because bears lack the fingerprint-style markings of a tiger or the spots of a giraffe, the AI had to analyze multiple images of each known individual and work out for itself how to tell them apart.

It’s a bit tricky. Bears don’t have as many distinctive features as people and the bears’ appearance changes with the seasons, including massive weight gain through the autumn.

“The software takes all kinds of measurements of the face in multiple dimensions and learns which features are stable in individuals,” said Clapham.

“We need to be able to recognize them in the fall and in the spring and our initial analysis suggests that it can.”

Ideally, the system will begin to identify bears as juveniles and then allow researchers to follow them during their fastest growth period, between two and five years old, and into adulthood.

The study was published Friday in the peer-reviewed journal Ecology and Evolution.

These new AI tools could revolutionize conservation and wildlife management.

Using “camera traps” scattered throughout the landscape to track the movements of bears would reduce the need to capture, tag and take samples from the animals.

“We could capture many more individuals with this method and track them, observe their movements in relation to food, and do much better population assessments,” said Clapham, who has spent the past 10 years observing grizzlies in B.C.

But why stop with bears?

AI “has already been applied to primates such as chimpanzees and gorillas, using human facial- recognition techniques,” she said.

The researchers hope that the system can be trained to work on other bear species and perhaps large herbivores such as endangered caribou.

“The challenge is that you would need a few photos of 50 to 100 known individuals of a species,” she said.

A joint project of UBC’s Marine Mammal Research Unit and computer scientists is focused on creating a killer whale recognition system that biologist Andrew Trites hopes will produce a real-time identification app for orcas that he can use in the field.

“It would help a lot of people if we could easily say whether a whale is transient or a resident as the rules for watching them are different, but the average person can’t tell the difference,” he said.

From a research standpoint, identifying individuals provides rich data on the animal’s movements, where it feeds and its general health.

It could also conceivably save their lives.

Two years ago, biologists attempted to provide veterinary treatment to a female killer whale named J50 Scarlet, who was observed to be ill.

“Once you give an animal a name it takes on more value for people, and if you follow them closely it has a family, a life history, and an individual story,” said Trites.