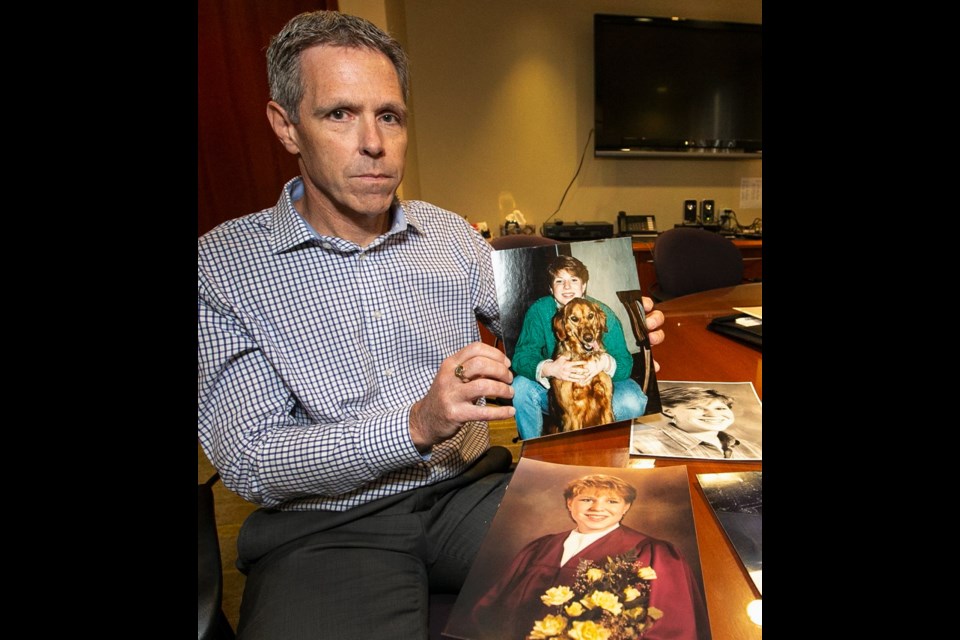

Photos of Tanya Van Cuylenborg are spread out on a desk, showing a smiling teen from Saanich on a high school trip to Paris, cuddling the family’s golden retriever, sitting on her brother’s shiny 1967 Mustang and behind the wheel of her father’s sailboat.

These happy snapshots are how her brother, John Van Cuylenborg, prefers to remember her, rather than the day he and his father identified her body in November 1987, after she was raped and killed in Washington state.

John Van Cuylenborg spent 31 years wondering whether anyone would be arrested for the killings of his sister, who was 18, and her 20-year-old boyfriend, Jay Cook.

Next week, he will face the man accused of the murders, a 55-year-old Seattle-area trucker named William Earl Talbott II, as his trial begins in Snohomish County Superior Court.

“I’ve been preparing for a trial for 31 years,” said John Van Cuylenborg, a Victoria-based lawyer. “I think it’s going to be very difficult. I’m expecting it to be tough, but it’s a necessary part in getting to where we want, which is having someone held accountable.”

Tanya Van Cuylenborg and Jay Cook were supposed to be on a quick overnight road trip to the Seattle area to buy parts for Cook’s father’s business.

On Nov. 18, 1987, the high school sweethearts boarded the Coho ferry to Port Angeles in the Cook family’s bronze 1977 Ford Club Wagon. They bought ferry tickets to Seattle at the Bremerton ferry dock at 10:16 p.m. and were never seen again.

Tanya Van Cuylenborg’s partially clothed body was found on Nov. 24, 1987, in a ditch in a wooded area of Parsons Creek Road in Skagit County, 20 kilometres south of Bellingham. She had been restrained with zip ties, sexually assaulted and shot in the back of the head. Cook’s body was found two days later nearly 150 kilometres away, near Crescent Lake Road just east of Monroe, Washington. He had been strangled and restrained with zip ties.

Studying at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver at the time, John Van Cuylenborg didn’t know his younger sister was heading off on a road trip, but remembers the phone call from his worried parents, Bill and Jean, on Nov. 20, the day after the couple was expected to return home. It was out of character for Tanya to be out of touch and the Van Cuylenborgs were trying to convince police that something was wrong.

Jean Van Cuylenborg was at home, supported by family friends, when she got a call from the sheriff’s office that a body had been found and was believed to be her daughter.

John and Bill Van Cuylenborg were in the Seattle area searching for the pair when they learned, via pay phone, that everyone’s worst nightmare was confirmed.

It was a solemn drive north to a funeral home in Mount Vernon, Washington, where the father and son identified Tanya’s body.

“That was the darkest of days,” John Van Cuylenborg said. “It was terrible.”

The family held a funeral at the University of Victoria’s Interfaith Chapel, filled with cousins, extended family members and the 18-year-old’s friends from Oak Bay High School. Beyond the overwhelming grief, the family was trying to comprehend why someone would kill two nice, quiet people.

“Everybody was asking why and couldn’t believe it had happened,” said John Van Cuylenborg. To this day, even with an arrest, the motive for the killing remains a mystery.

“I still think of it as the ultimate example of wrong place, wrong time,” he said. “There’s just not an explanation, other than they just crossed paths with the wrong person at the wrong time and we don’t know why.”

Over the years, the only major breakthrough from police was when they caught the person, claiming to be the killer, who was sending the Cook and Van Cuylenborg families disturbing letters. In 2010, police tracked down a homeless Vancouver man with mental illness who admitted to sending the letters. Through a DNA test, police ruled him out as a suspect.

“That was the only concrete development over the 31 years, to rule someone out,” John Van Cuylenborg said.

John Van Cuylenborg knew that in 2018, investigators were working with a company called Parabon Nanolabs, which was using advancements in DNA technology to find new leads in the case.

In April 2018, the Snohomish County Sheriff’s office released three images of what the killer might have looked like at age 25, 45, and 65, based on DNA found on Van Cuylenborg’s body. The technology called snapshot DNA phenotyping can determine a person’s eye, skin and hair colour, facial features and ancestry.

But the real break came a month later, when the lab used genetic genealogy to identify a suspect. It’s the same technology that was used to arrest Joseph James DeAngelo in connection with the Golden State Killer case, in which a serial killer in California is believed to have been responsible for 13 murders and more than 50 rapes.

On May 17, 2018, John Van Cuylenborg got a call from Snohomish County Det. Jim Scharf telling him Talbott had been arrested.

“I said: ‘Where is he?’ [Scharf] said: ‘In the back seat,’ ” John Van Cuylenborg recalls. “That sent a shiver down my spine, to think: ‘Wow, this guy is in custody.’ ”

Cece Moore, the genetic genealogist who worked on the Cook and Van Cuylenborg case, said she compared the DNA collected in 1987 to the DNA of people who had shared their results on GED Match, a public website where people can discover their genetic relationships.

Moore was able to build family trees, starting with the second-cousin or great-grandparent level. Moore looked for living people who fit the DNA profile, and two of the closest matches converged, intersecting into a marriage. From that marriage, there was only one son, leading to the only person who could carry the mix of DNA.

Police obtained a coffee cup belonging to Talbott and found the DNA was a match.

“If it hadn’t been for genetic genealogy, we wouldn’t be standing here today,” Scharf said at a press conference in May 2018.

Last month, in another case where police use of ancestry databases led to a breakthrough in a 30-year-old case, Timothy Forrest Bass was found guilty of first-degree murder in the death of 18-year-old Mandy Stavik in November 1989 in Whatcom County, Washington.

John Van Cuylenborg knows there are privacy concerns associated with genetic genealogy, but said individuals voluntarily upload their DNA to genealogy websites such as GED Match, whose terms of service explicitly state that the information can be provided to law enforcement for sexual assault and murder cases.

Other than his 20-year career as a truck driver and the fact that he has no criminal record, little is publicly known about Talbott or how he might have come into contact with the Saanich couple. On May 31, when Talbott was informed that his trial would be delayed a week, he said: “My life’s been on hold for greater than a year now for a crime that I did not commit,” according to the Everett Herald newspaper.

It was one of the few times the suspect’s voice has been heard in Snohomish County Superior Court.

For John Van Cuylenborg, 52, there’s no such thing as closure. “Nothing is bringing these kids back,” said the father of two teenage girls, one of whom is the same age his sister was when she died. “It’s just an open wound that never really heals.”

Jury selection begins on Tuesday and the trial is expected to last four weeks.