Earlier this year, the province hit mining giant Teck Resources Ltd. with the largest administrative penalty for an environmental violation: nearly $15.5 million.

The province said it issued the penalty because the company failed to get one of its required water treatment facilities — which would strip out selenium — operational by the end of 2018.

Selenium, a trace element in coal that can be harmful to fish and humans at higher concentrations, has been leaching for decades from the company’s vast coal operations into streams and rivers in the Elk Valley in B.C.’S southern Interior.

Additional penalties for exceeding nitrate and selenium levels brought the administrative penalty total to more than $16.5 million.

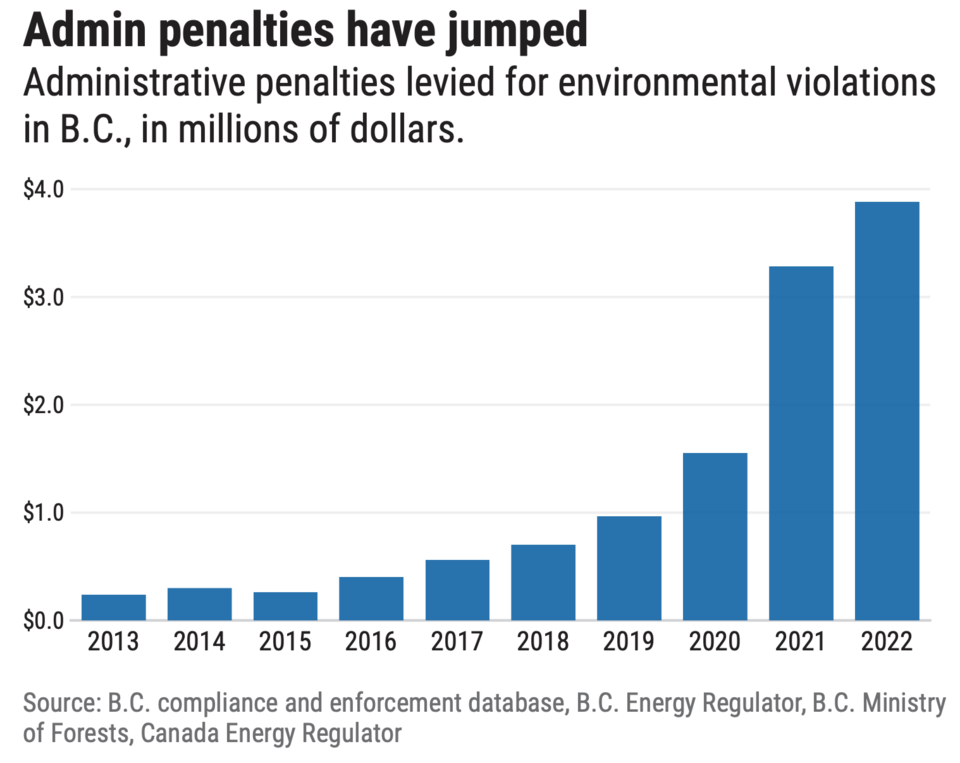

The massive fines underscore an emerging reality for polluters in B.C.: The province is issuing an increasing number of administrative penalties.

In 2013, there were only $241,000 in such penalties issued in B.C.

By 2022, the amount had grown to $3.86 million, according to an analysis by Postmedia of administrative penalties issued by provincial and federal regulators.

The analysis includes information compiled from B.C.’s online compliance and enforcement database, the province’s forestry and environment ministries, the B.C. Oil and Gas Commission and the Canada Energy Regulator, formerly the National Energy Board.

Between 2013 to 2022, administrative penalties issued by B.C. and Ottawa for environmental violations totalled $12.2 million. So far in 2023, the combined penalties have reached nearly $17 million.

But while the number and dollar value of administrative penalties has increased, some critics question how effective they are.

They suggest the fines will do little to change behaviour and that some companies chalk up these fines as simply an expense that can be absorbed, given their huge revenues and profits.

For example, the forest industry’s manufacturing sector had sales of $21 billion in 2021. In the mining sector, Teck alone had revenues of $17.3 billion in 2022 and a profit of $4 billion.

“The penalties, I think it’s just the cost of doing business,” said Wyatt Petryshen, a mining policy and impacts researcher for the conservation group Wildsight in the Elk Valley.

The increased penalties might be enough to “raise the eyebrows” of Teck and maybe even scare away a few investors, but the penalties still pale in comparison to its billions in annual profits, said Petryshen.

“The selenium — it’s a perpetual problem. It’s not solved. It’s not getting solved,” he said.

Unlike fines that result from court convictions, administrative penalties can be issued directly by provincial officials for violations of B.C.’s environmental and safety laws, eliminating the often lengthy and costly legal prosecution process.

The administrative penalties can be appealed, as Teck has done with the $16.5 million in penalties issued in 2023.

A company that exceeds the limits for harmful heavy metals in a permit that allows effluent to be discharged to waterways can be issued an administrative penalty. The same goes for exceeding air pollution limits from a pulp mill, for example, or improperly controlling sediment from entering environmentally sensitive areas during construction of a pipeline.

Administrative penalties are intended to change behaviour and encourage compliance with regulatory requirements.

According to provincial officials, that makes them different from court-issued fines, which are intended to punish wrongdoing and address impacts to society and the environment, a distinction set out in a 2015 Supreme Court of Canada decision.

However, critics suggest companies’ behaviours could be better changed by the increased use of court fines, which have higher penalty limits and come with more public censure. The province could also use sanctions, which can suspend or take away permits that authorize pollution discharges, which have a much higher consequence than fines, say critics.

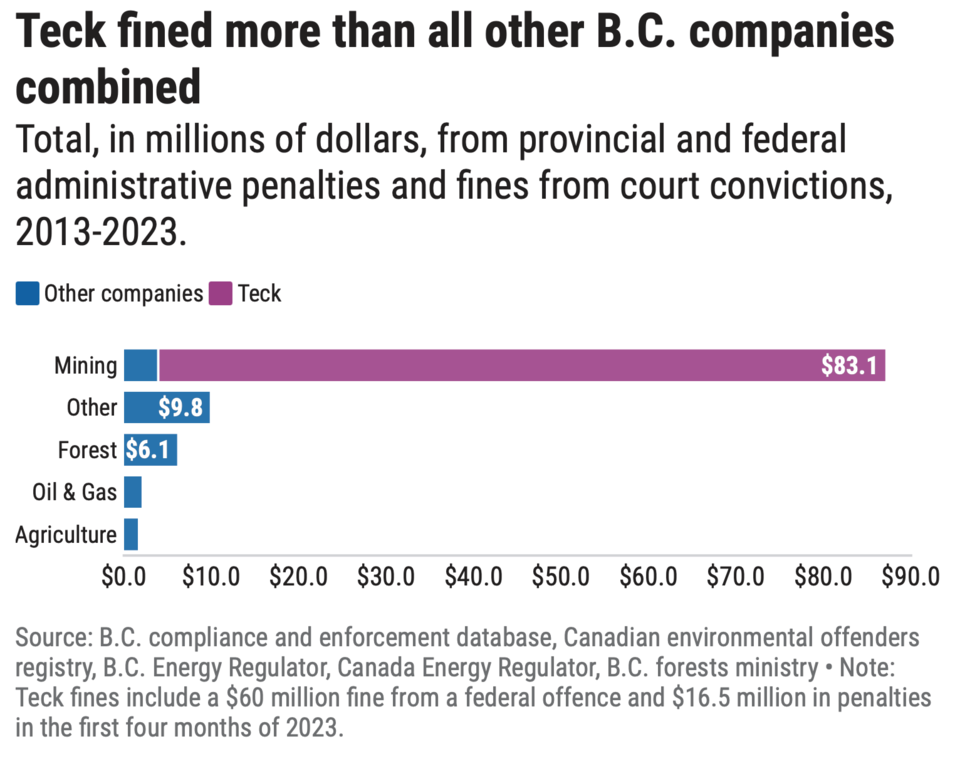

Teck is the most penalized company for environmental violations in B.C., according to Postmedia’s analysis.

In addition to $1.03 million in administrative penalties issued between 2013 and 2022 and the $16.5 million in penalties issued in 2023, the company has also, in the past decade, been subject to $4.1 million in fines from court prosecutions under B.C. laws and another $61.4 million in fines from court prosecutions under federal laws for polluting the environment. The federal court fines include $60 million in 2021, the largest fine imposed under the Fisheries Act, for contaminating waterways in southeastern B.C., including the Fording River.

Teck’s total administrative penalties and court fines add up to $83.1 million and account for 78 per cent of all fines and administrative penalties issued since 2013 in B.C., according to Postmedia’s analysis.

Teck Resources Ltd. is a huge company in British Columbia, employing more than 7,100 people at its four mines that produce steelmaking coal, another that produces copper and a smelting operation.

The coal-mining process literally takes mountains apart, with huge shovel equipment digging out the coal that has been blasted into finer pieces. Huge trucks with tires the size of elephants haul the coal to processing plants, after which the coal is loaded onto trains to Vancouver, where it goes onto ships for export overseas.

Recently, Teck announced it is exploring a spin-out of its coal assets in B.C. into a separate company as part of a shift to mining metals that will fuel a greener economy — and is also the subject of an unsolicited takeover offer from Swiss mining giant Glencore PLC.

There is little doubt that Teck, the second-largest overseas exporter of steelmaking coal, is a huge contributor to B.C.’S economy.

But Teck’s environmental compliance record is not stellar.

In more than 250 inspections between 2017 and 2023 outlined in the province’s compliance and enforcement database, Teck failed compliance of its permits or the province’s regulations 84 per cent of the time, according to Postmedia’s analysis.

Among those were failures of toxicity tests of its discharge on tiny water fleas. The quarterly tests act as a sensitivity test on the toxicity of effluent from mining operations.

Ultimately, Teck was issued a $120,000 administrative penalty in 2020 but not before there were 28 toxicity test failures between 2014 and 2018 and three more failures in 2018 and 2019.

In responses to Postmedia questions, Teck did not directly respond with reasons for its high failure rate of inspections.

Instead, the company pointed to an investment of $1.2 billion so far to improve water quality in the Elk Valley and a plan to invest another $750 million in the next two years.

“Of note, since 2015, we have met water quality limits at monitoring stations throughout the Elk Valley an average of 95 per cent of the time. Concentrations and compliance at these locations are influenced by seasonal variation inflow as a result of snowpack melt and precipitation,” Teck spokesman Chris Stannell said in a written statement.

Poor compliance record

Teck is not alone.

Other companies also have poor compliance records.

Paper Excellence’s Skookumchuck pulp mill in southeastern B.C. was out of compliance in some aspect in all 19 of its inspections between 2018 and 2022, according to records in the B.C. compliance and enforcement database.

Non-compliance with its permits included exceedances of discharges into creeks, exceeding limits for airborne pollutants and a lack of leak detection in a landfill. Ultimately, Skookumchuck received nearly $175,000 in administrative penalties.

Paper Excellence is owned by Jackson Wijaya, the grandson of a Chinese-indonesian billionaire who founded the giant conglomerate Sinar Mas Group. The company’s Mackenzie pulp mill in northern B.C., now permanently closed, also has had compliance issues. It failed nine of 10 inspections between 2018 and 2021, including for exceedances of air pollutants such as hydrogen sulphide. There were 130 hourly exceedances between 2014 and 2018, some of them triple the limit, inspection records show. The company was fined $254,000 for the violations.

Provincial records show that the mills of West Fraser Timber Co. Ltd., a leading forest products manufacturer in B.C., were out of compliance in two-thirds of 69 inspections between 2018 and the early part of 2023 under the Environmental Management Act. Those included exceeding air pollution limits at a plywood plant and failure of toxicity tests done on rainbow trout in its effluent stream from a pulp mill, both operations in north-central B.C.

West Fraser has been handed $66,000 in administrative penalties.

Delfresh Mushroom Farm Ltd., which has operations in the Fraser Valley, failed some aspect of 13 of 15 inspections between 2017 and 2022 for repeated violations of release of “brown” water from its operations to the environment, having no plan to deal with effluent, not collecting and treating air emissions and not carrying out fixes required by the province. Delfresh has been fined nearly $65,000 for these violations.

Coastal Gaslink, TC Energy Corp.’s 670-kilometre natural gas pipeline under construction in northern B.C., has been the subject of nearly 500 inspections between 2019 and 2022. The $14.5-billion pipeline will feed Canada LNG’S $18-billion liquefied natural gas terminal in Kitimat, which will export the gas overseas.

TC Energy has noted it has a 90 per cent compliance rate compared with the industry standard of 82 per cent, but that figure only includes inspections by the B.C. Oil and Gas Commission, recently renamed the B.C. Energy Regulator.

Under inspections by the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office (EAO), which has responsibility and authority to ensure a project is being constructed to agreed conditions, it has a compliance rate of just 30 per cent in more than 60 inspections between 2019 and 2023, including for repeat offences of erosion and sediment control, a concern because sediment runoff can harm sensitive wetlands, creeks and rivers.

The EAO’S first administrative penalties were issued to Coastal Gaslink.

The three penalties in 2022 and 2023 total $456,200.

Joel Forrest, Coastal Gaslink’s project vice-president of stakeholder relations, says the company takes administrative penalties and the role of regulators very seriously.

Forrest noted that constructing a project such as Coastal Gaslink is “incredibly” complex and covers diverse terrain. The company’s environmental management plan provides flexibility to adapt and respond to issues like erosion and sediment control as they arise, he said. In many cases, the best way to protect the environment and minimize disruption to the land is by completing construction quickly and restoring the area, said Forrest.

He said that in the company’s experience, the EAO takes a prescriptive approach to environmental protection plans and the company has learned to work collaboratively with them to meet their “high” regulatory standards.

“We are feeling good about the progress we’ve made to address concerns such as erosion and sediment control,” said Forrest.

He noted that a compliance agreement signed with the EAO last year provides greater clarity on the measures expected by the province.

Forrest said while the public is familiar with administrative penalties, the more significant costs to the project are the exceptional steps the company takes to enhance its environmental compliance. That includes developing and implementing extensive work execution plans, monitoring by independent erosion and sediment control auditors required by the EAO, and employing and training erosion and sediment control qualified professionals.

Said Forrest: “These are significant expenses, but we are committed to safely delivering B.C.’S natural gas to Canada’s allies while protecting our environment.”

Penalty powers have increased over time

The authority to issue administrative penalties by various agencies and ministries has rolled out slowly in B.C. over the past two decades.

Under the Environmental Assessment Act, for example, the EAO received that power in 2020.

The Forests Ministry obtained the authority to issue administrative penalties nearly two decades ago, in 2005. Administrative penalty authority was added to the Environmental Management Act in 2014 and under the Mines Act in 2017.

Postmedia’s analysis found the addition of the penalty authority under the Environmental Management Act has been the main driver in the increasing number of administrative penalties and the rising total dollar value of fines issued since 2015.

Penalties issued under the act accounted for nearly 50 per cent of the $12.2 million in penalties issued between 2013 and 2022. The next largest dollar amount of penalties was delivered under the Forest and Range Practices Act, at about 30 per cent of the total.

Penalties under the Environmental Management Act have skyrocketed since 2015, when just $15,000 was issued. In 2020, $700,000 in penalties were issued, in 2021 $1.6 million and in 2022 $2.1 million.

In response to Postmedia’s questions, the B.C. Environment Ministry said it believes administrative penalties are an effective tool to change behaviour and encourage compliance.

It’s why the ministry has increased its use since they were introduced in 2014, David Karn, a senior public affairs officer with the ministry, said in a written statement. And it’s also why some penalties are large, intended to deter non-compliance where parties stand to gain sizable financial benefits, and where they otherwise might view a smaller penalty as simply the cost of doing business, said Karn.

“The high rates of non-compliance in inspections for some regulated parties is a significant concern for the ministry, as non-compliance with environmental requirements can result in environmental impacts and/ or risks to human health,” he acknowledged.

However, ministry officials noted that while it may appear that some sites have repeated issues of non-compliance and are not addressing the issues, the issues may be independent from one another.

The ministry said it views administrative penalties and fines from court prosecutions as very different tools intended to fill different roles.

Penalties have not replaced court convictions, said Karn.

| Ministry | Legislation | Enacted | Penalty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | Environmental Assessment Act | March 2020 | $750,000 |

| Environment | Environmental Management Act | June 2014 | $500,000 |

| Forests | Forest & Range Practices Act | March 2015 | $500,000 |

| Mining | Mines Act & Health, Safety and Reclamation Code for Mines | February 2017 | $500,000 |

| Oil and Gas | Oil & Gas Activities Act | February 2011 | $500,000 |

Source: B.C. legislation | NOTE: Some legislation allows penalties to be multiplied by the number of days in violation.

Andrew Gage, a staff lawyer for West Coast Environmental Law, a B.c.-based group that supports environmental lawsuits, believes there is a question of whether the province’s enforcement record is making a difference — and whether the environment is being protected. He noted that court convictions convey more “cultural disapproval.”

He believes court convictions have been underused for decades and notes that administrative penalties have historically meant small monetary fines.

So, increasing administrative penalties doesn’t carry the heft of court prosecutions, argues Gage.

Postmedia’s analysis shows that at the same time as administrative penalties have been increasing, fines from court prosecutions, at least under B.C. statutes, have been dropping since a peak of $3.4 million in 2016. In 2022, there were zero fines from court convictions under provincial laws.

Administrative sanctions, another tool that critics cite, have been used 3,600 times since 2006.

However, almost all those sanctions have been directed at individuals, removing, for example, a person’s right to fish or hunt recreationally, shows Postmedia’s analysis.

Very few sanctions were targeted at commercial enterprises: 12 at hunting guide outfitters, one at a pest control company and two at Cobble Hills Ltd.

Cobble Hill had its permit suspended in 2017 that allowed a quarry it owned to receive and store contaminated soil upstream from Shawnigan Lake on Vancouver Island.

No administrative sanctions that suspended or removed permits were handed out to any major companies in the past decade.

Said Gage: “Usually, if someone continues breaking the law, they get locked up or they get their licence taken away. But because these companies are too big to fail, I guess, the government has taken a 'we’ll-just-continue-to-ding-them-with-these-penalties approach.’”

These are significant expenses but we are committed to safely delivering B.C.’s natural gas to Canada’s allies while protecting our environment.