The doodle. We’ve all done it, during a classroom lecture or a meeting at work.

At first glance, it’s a trivial waste of time. But upon closer examination, those squiggles, drawings of animals or tiny sketches of the boss in a gorilla suit seem to have some value.

Studies have shown that people benefit from doodling. And author Sunni Brown sees the doodle as a flash point in nothing less than a revolution in the way we learn. In fact, her new book, due out in the fall, is called The Doodle Revolution: Unlock the Power to Think Differently (Portfolio).

“It is instinct,” she says of the use of visual language. “Just like there’s a linguistic grammar ... there’s also a native visual language for all people. It’s very natural and flows out of all of us.”

Brown explains that there is a “visual alphabet,” a set of 12 symbols that can be used to articulate any conceivable concept. She says that rather than talking about a complex topic, it might help to doodle it as a new way of expressing the idea.

At a conference in 2011, Brown told her audience, “Our culture is so intensely focused on verbal information that we’re almost blinded to the value in doodling.” She says doodling is a powerful tool that we, as adults, need to relearn. Kids, it seems, have it right.

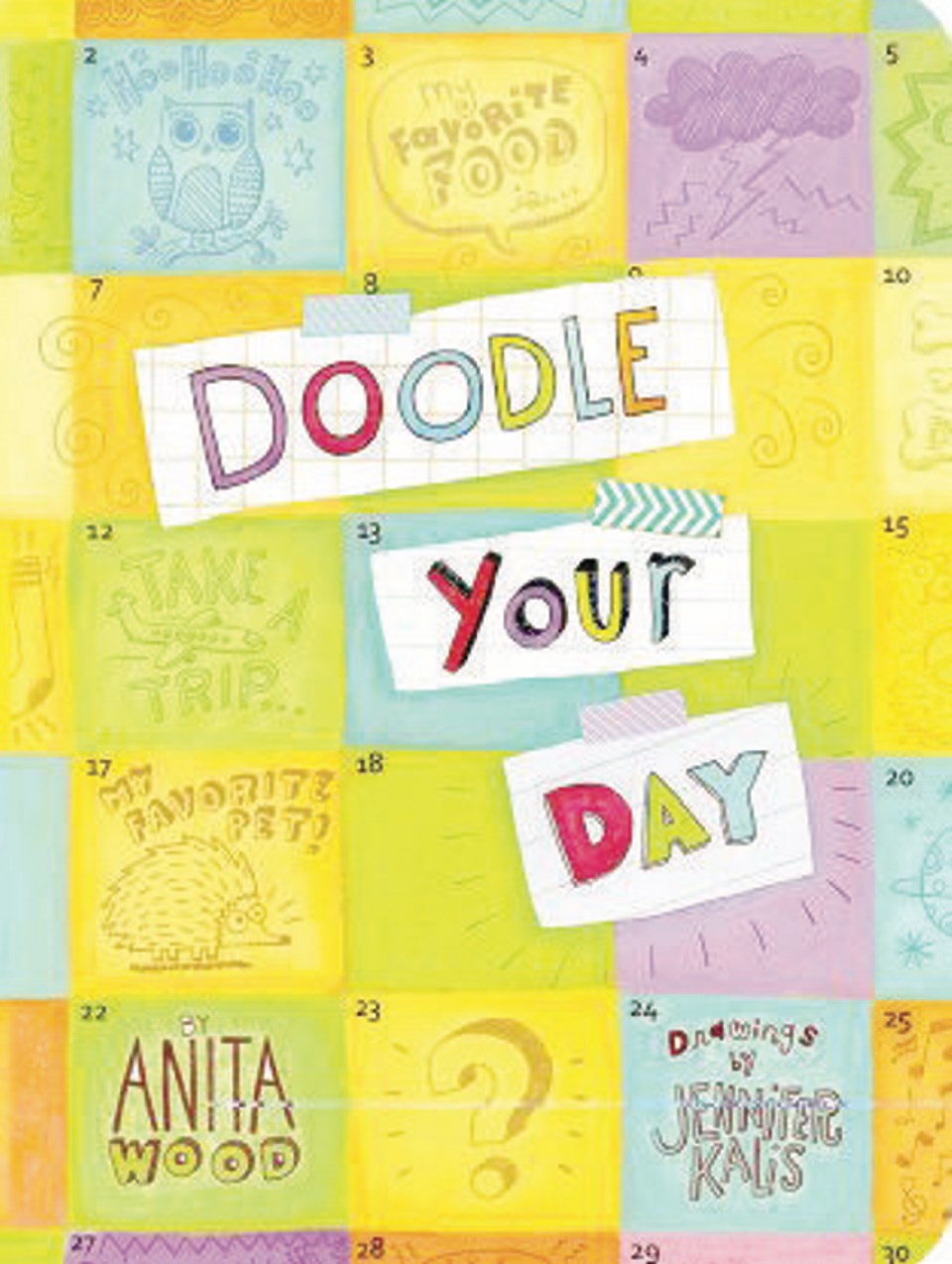

Anita Wood, whose new book, Doodle Your Day (Gibbs Smith), gives eight-to-12-year-olds a day-by-day forum for doodling, says that an inherent desire to create or doodle starts when children are handed their first pencil or crayon, “or even earlier, when they are eating their mashed carrots and peas. My children liked to paint on their high-chair trays using their mushy Zwieback toast as soon as they developed their dexterity and hand co-ordination.”

Brown, who lays out her strategy to save the doodle at sunnibrown.com/doodlerevolution, explains doodling employs three learning areas — visual, auditory and kinesthetic — and “dramatically enhances the experience of learning.”

That notion was confirmed in a study published in 2009 in the journal Applied Cognitive Psychology. Psychologist Jackie Andrade of the University of Plymouth in England found that people who doodle remember 29 per cent more than those who do not. Andrade suggested that when people doodle, they don’t daydream. You can be looking directly at a teacher or speaker, appearing to hang on every word, but your mind is miles away. Doodling, on the other hand, forces the brain to keep working and not daydream.

— Chicago Tribune