Smaller than an atom but fundamental to understanding the nature of the universe, the Higgs boson particle is a scientific discovery that will likely transform our lives, says a University of Victoria particle physicist.

Prof. Michel Lefebvre, one of eight UVic physicists involved in the worldwide project, said the discovery last summer in Geneva, Switzerland, of a subatomic particle is enormous news.

Other members of the team at UVic are scientists Justin Albert, Alan Astbury, Richard Keeler, Robert Kowalewski, Robert McPherson, Randall Sobie and Isabel Trigger.

Lefebvre will be giving a free public lecture on the Higgs boson tonight from 7 to 9:30 at the David Lam Auditorium at UVic. Seating is limited and the event is expected to be well attended. It will also be simultaneously webcast to an auditorium in an adjacent building.

So far, the particle seems to behave in a way predicted for the Higgs boson, first theorized by physicist Peter Higgs in 1964. It’s the type of scientific discovery that is so big, it occurs only once every several decades.

It’s as big for physics as the 1953 decoding of the DNA molecule was for biology, Lefebvre said in an interview.

And while the Higgs boson may not be immediately or obviously useful, it won’t be long before human ingenuity is using the knowledge in ways not even considered.

This process of transforming scientific theory into applications can be likened to the way Albert Einstein’s 1905 theory of relativity was put to work decades later generating power.

It can also be compared to the way theories of the curvature of space and time are now at work in the GPS device found in the family car.

“I wish I had the imagination to think what we are going to do with this knowledge in the medium or long term,” Lefebvre said.

Lefebvre, 49, has been engaged since 1989 in a search for evidence of the Higgs boson. Sometimes nicknamed “the God particle” mostly by the media, it’s the particle that allows matter to actually have mass.

“This is of paramount importance because these discoveries then impact our understanding of how the universe evolved in the fractional seconds after the Big Bang,” he said.

It’s a search for something so small, scientists aren’t even sure it actually occupies space.

Lefebvre said if an atom could be imagined to be the size of a football field, most of it would be empty. A tiny electron would spin around the exterior. And at the centre, the nucleus, with its protons and neutrons, would be the size of a beetle.

And if the nucleus were blown up to the size of a football field, then Higgs boson would be tinier than a hair on one of the beetle’s legs.

The particle occupies a field, called the Higgs field, something like the electro-magnetic field (upon which cellular telephones rely). And this Higgs field flows through everything in the universe.

So, atoms are composed of electrons, protons and neutrons. And they are all composed of quarks (another subatomic particle) held together by gluons, and inside them exists the Higgs boson.

“It gives you vertigo when you start looking at all of this,” he said. “It’s fascinating.”

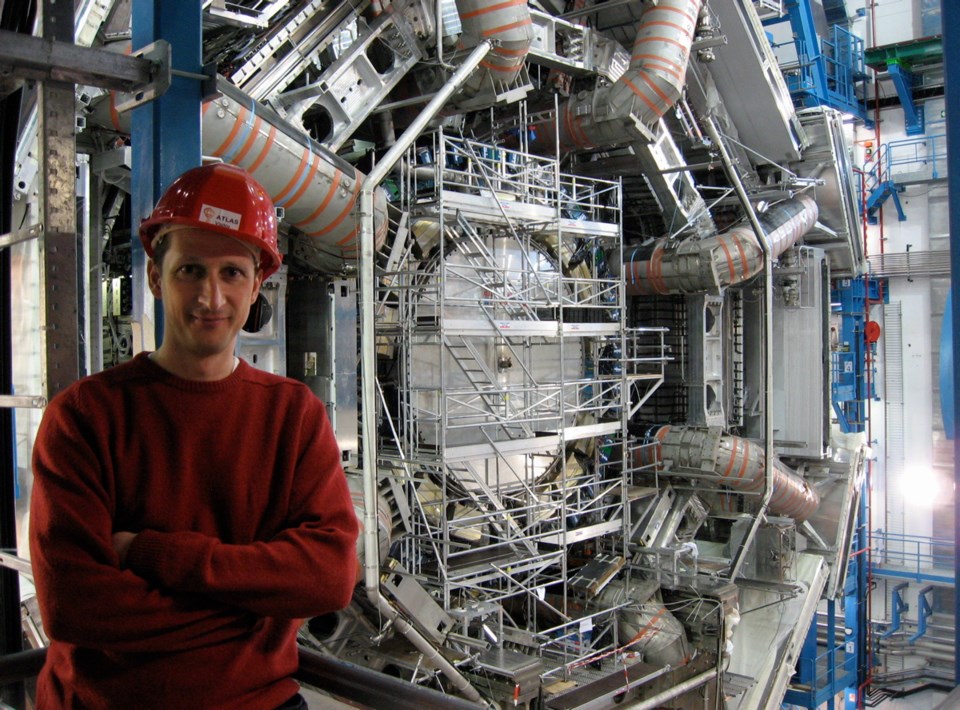

Lefebvre was also instrumental in co-ordinating Canada’s participation in the ATLAS project. ATLAS is a huge particle detector occupying the underground space of a multi-storey building beneath the Alps.

It was built to examine the subatomic debris that results when protons are smashed together in the Large Hadron Collider — a 30-kilometre tunnel built under the Swiss-French countryside.

Lefebvre said so far the experiments in Switzerland have been creating mountains of data, now being analyzed by worldwide arrays of computers and scientists.

“We are still not entirely sure that it is the Higgs boson,” Lefebvre said. “But it looks like it, behaves like a particle that is at least like a Higgs boson would.

“It is the first time we have seen something like this.”