CHICAGO — When New Yorker cartoonist Pat Byrnes and his wife, Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan, had their first child, there was no discussion about who would stay home.

“It was too obvious,” Byrnes says. “What’s to discuss? It was a no-brainer.”

His hours were flexible. Hers, not so much. He worked from home. Her, not so much.

So when Madigan’s maternity leave was up, Byrnes became the at-home caregiver for their now eight-year-old daughter and, eventually, her now five-year-old sister. He remains in the role today, shuttling the girls from their Chicago home to school and lessons and play dates, preparing meals, sweeping up the crumb blizzards. (“If I used a rake instead of a broom, I could create my own Zen garden underneath the kitchen table.”)

He creates cartoons while Rebecca and Lucy are at school. In recent years, work happened during their naps.

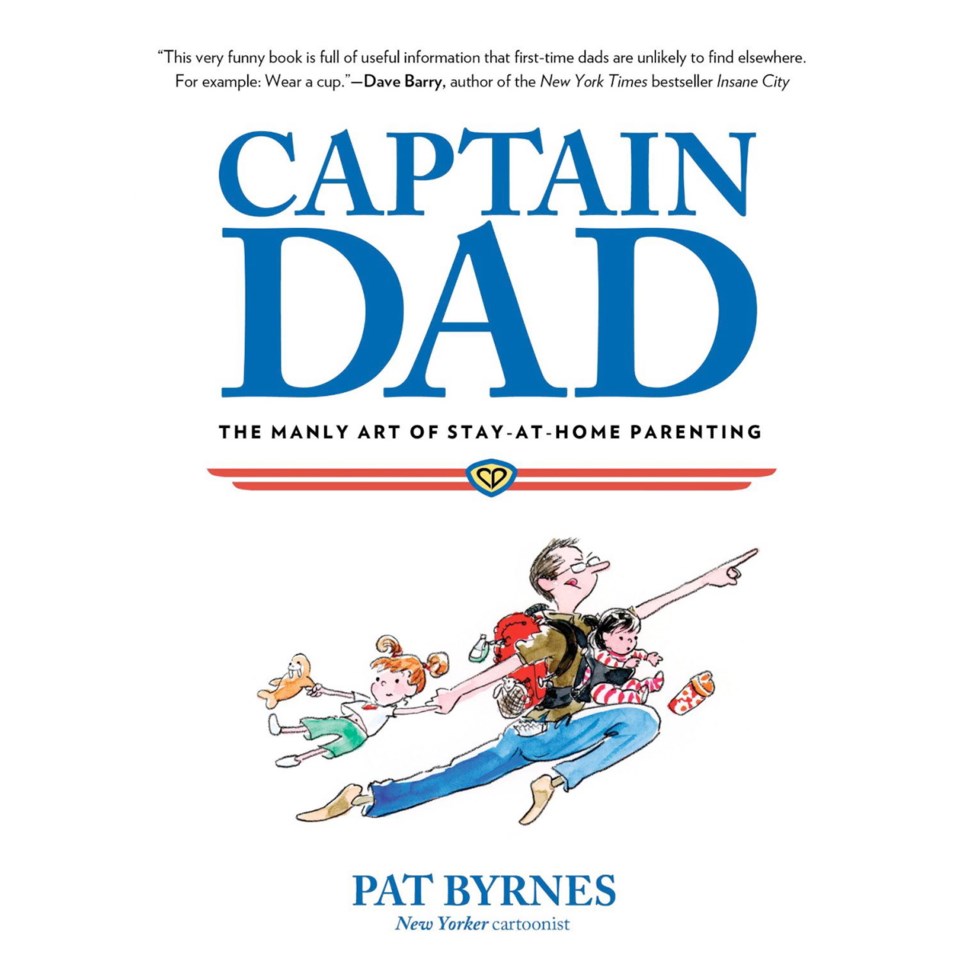

“Being a stay-at-home parent is the toughest job there is. For a woman or a man,” he writes in his new book, Captain Dad: The Manly Art of Stay-at-Home Parenting (Lyons Press). “There. It’s been said. By a man. So it has to be true.”

A stay-at-home dad is not the cultural oddity he once was — “the decimation of the global economy has been a boon to us,” Byrnes writes. But statistics imply that Byrnes’ and Madigan’s choice hasn’t reached “no-brainer” status everywhere.

About 158,000 American men stay home full-time with their kids for at least one year, according to the 2010 census. About 5.1 million American women do.

Countless factors contribute to the disparity. And every family deserves the right to design its own work-life landscape.

Still. Byrnes is hoping to see those numbers level out a bit.

He has little patience for antiquated gender roles. And he has answers for the arguments against dads staying home.

“Men aren’t hard-wired for child-rearing?” (I hear that one a lot.)

“We’re not,” he replied. “We don’t have hips. Yeah, we’ve got upper body strength, but that wears out a lot faster than a hip.”

But when did hard-wiring become an excuse for anything?

“Men make things,” he says. “We figure things out. Parenting is the ultimate do-it-yourself project. You’ve got to use your tools and problem solve. Guys climb rock walls and mountains because it’s a challenge. Here’s a challenge you can wake up to every morning.”

He embraces studies that show testosterone levels decline when men have children — and continue to decrease the more time spent with kids.

“The loss of testosterone does not signify the end of manhood,” he writes. “It signifies the end of boyhood. To which I say a manly hurrah.”

“Testosterone,” he reasons, “makes guys take steroids until their testicles retreat into their abdominal cavities just so they can do one thing or another with a ball — which of course ‘they’ really can’t do, because it’s the drug, not them, doing it.”

Bring on the decrease, he says.

“Testosterone is for boys the way coolness is for kids,” he writes. “Kids need to define themselves by something when they have yet to do anything significant with their lives. It’s the place-holder for real achievement. Like raising kids. Not just spawning them. Raising them.”

He points to studies that quantify the advantages of a caring, involved father.

“I’d think that, in this era of parenting as a contact sport, this competitive edge alone would justify encouraging men to be more, well, manly,” he writes. “Fatherly.”

Not every family can financially swing a parent at home full time. Byrnes isn’t taking a moment for granted. “It’s brutally exhausting and it beats you down,” he says. “But you get to be there.”

In his epilogue, Byrnes elaborates on his decision to stay home. “Someone had to do it. Period,” he writes. “As long as my wife is already serving our children through public service, that someone will be me.

“In the end, raising children is not a woman’s job or a man’s job,” he adds. “It’s all of our job.”