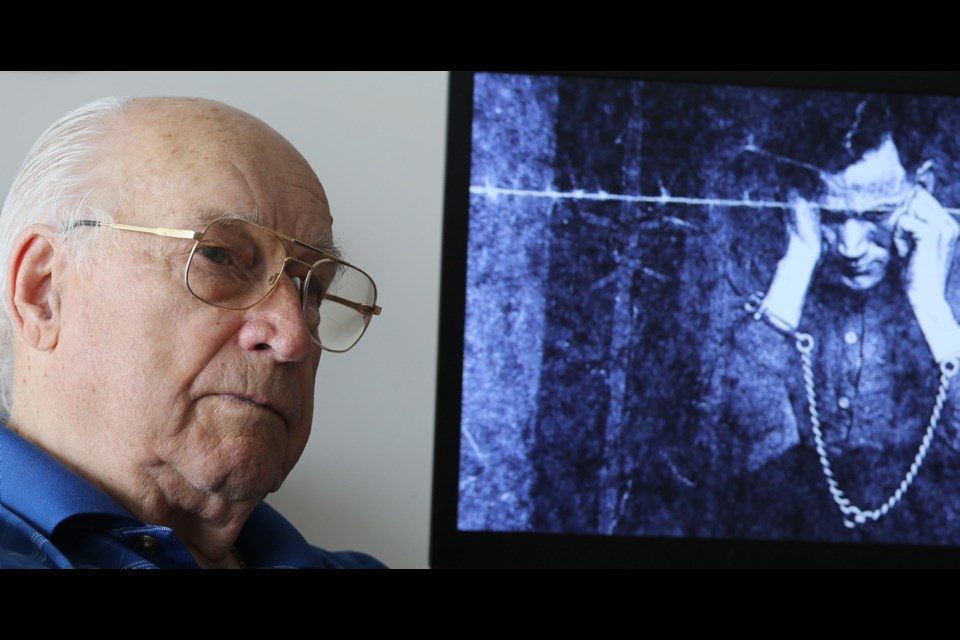

Second World War veteran Ken Curry remembers well the disastrous Battle of Dieppe, but made no plans to memorialize it on its 71st anniversary Monday.

“I’ve got the memories of my buddies, and my time on the beach, and the battle. I’ll never forget,” Curry, 91, said in an interview at his Sidney home.

“You can ask, ‘Was it any good?’ and I’ll say, ‘It wasn’t any good at all,’ ” he said.

The raid on Dieppe was long hailed as a valuable rehearsal for the D-Day landings that would later liberate France. More recently, however, as historians have gained access to previously sealed documents, Dieppe has become recognized as one of the worst disasters of the Second World War.

Originally imagined as a quick in-and-out — a raid in force — it quickly turned into a slaughter for the 5,000 Canadians of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division who were shipped to the French town of Dieppe and deposited on its beach.

About 900 men were killed, nearly all of them Canadians. Another 586 were wounded; 27 died later of wounds or in prison camps, and 1,874, including Curry, then a private with a mortar crew, were taken prisoner.

Timothy Balzer, a Canadian military historian, author and former University of Victoria instructor, said the raid was a disaster largely unacknowledged in Britain at the time because of wartime censorship. The only pointed questions were raised in Canada because the scale of the disaster was too large to ignore.

“It didn’t make a lot of sense to begin with, and the planning was very amateurish,” Balzer said in a telephone interview from his home in Powell River. “And afterward, there was an attempt to distract from the truth.”

Balzer said the Dieppe Raid was pushed by three people, Vice-Admiral Louis Mountbatten, later Lord Mountbatten, and two Canadians, Lt. Gen. Charles McNaughton and Gen. Harry Crerar.

According to Balzer, Mountbatten saw a Dieppe operation as a credit for his Combined Operations section. Combined Operations was designed to bring army, navy and air force units together to raid and strike at Nazi-held Europe.

Generals McNaughton and Crerar, meanwhile, had fought hard to keep Canadian troops together under Canadian command. And they wanted Canadian troops to see some action.

Canadians troops, after all, had spent two years training in England. They were derisively nicknamed “the Home Guard” after the English militia troops comprising large numbers of seniors too old to fight.

“It wasn’t a compliment,” Balzer said.

But the British Navy did not provide a pre-landing bombardment with heavy guns. There was little support from the Royal Air Force, and the German troops were ready and waiting.

Dieppe needs to be remembered for two things, Balzer said.

“It should be remembered as a disaster in terms of how it was carried out. But the bravery of the men has to be remembered. They did their best against an objective that was probably unattainable,” he said.

“They kept going forward anyhow, at least when they could.”

Curry’s memories are of “all hell breaking loose” the second the ramp on the landing craft went down.

He was a private in a seven-man mortar crew, with the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry. Four of Curry’s crew were killed almost immediately. The survivors barely made it more than a few metres up the beach.

“We couldn’t move. The fire was too heavy,” Curry said.

He managed to fire off all 30 of his mortar rounds. He then crouched down while a disabled tank fired off all its rounds, leaving him hard of hearing to this day.

Finally, after about six hours, a smokescreen was laid down for the Canadians to use cover to withdraw.

Curry tried to get on two boats. The first was too full, but with a life preserver, he managed to swim to a second to find it full of corpses and drawing too much enemy fire, so he continued to swim.

Eventually he washed up on the French beach, dressed only in his underwear. He had kicked off his boots, pants and jacket in the water.

When he encounters a German soldier, Curry considers himself lucky he was so poorly dressed and bedraggled. He believes if he had managed to hang onto any of his uniform, he might have looked too formidable and been shot.

He was taken away and reunited with his brother, also dressed in underpants. The two hugged and wept and were marched off to spend the rest of the war in prison camps.

At the time of Dieppe, Curry had only recently turned 20. He had also just finished his honeymoon with Norma, then a young woman with the Royal Air Force and, unknown at the time, pregnant with their first child.

When Curry returned to England, Norma told him they had a little girl. The couple went on to have two more children.

Ken and Norma returned to Canada, where he worked most of his life at the Stelco steel plant in Hamilton, Ont. He also commanded an army cadet corps in Hamilton before retiring and moving to Sidney.

There was a ceremony in a Hamilton Park on Monday morning to mark the anniversary of Dieppe with four veterans of the battle on hand. Fewer than 10 are believed to be living. Curry thought it was too far for him and Norma to travel.

“I’ll lie in bed at night sometimes and I’ll think of my time on the beach and my buddies. They were all so damned young and they shouldn’t have died,” he said.

“Over the years, it’s been asked what did we do and what did we get. Well, we didn’t get anything as far as I’m concerned, except killed.”