RALEIGH, N.C. — A celebrated author is facing accusations that he lied in his best-selling book that details his near-death experience and what he says was his journey to heaven and back.

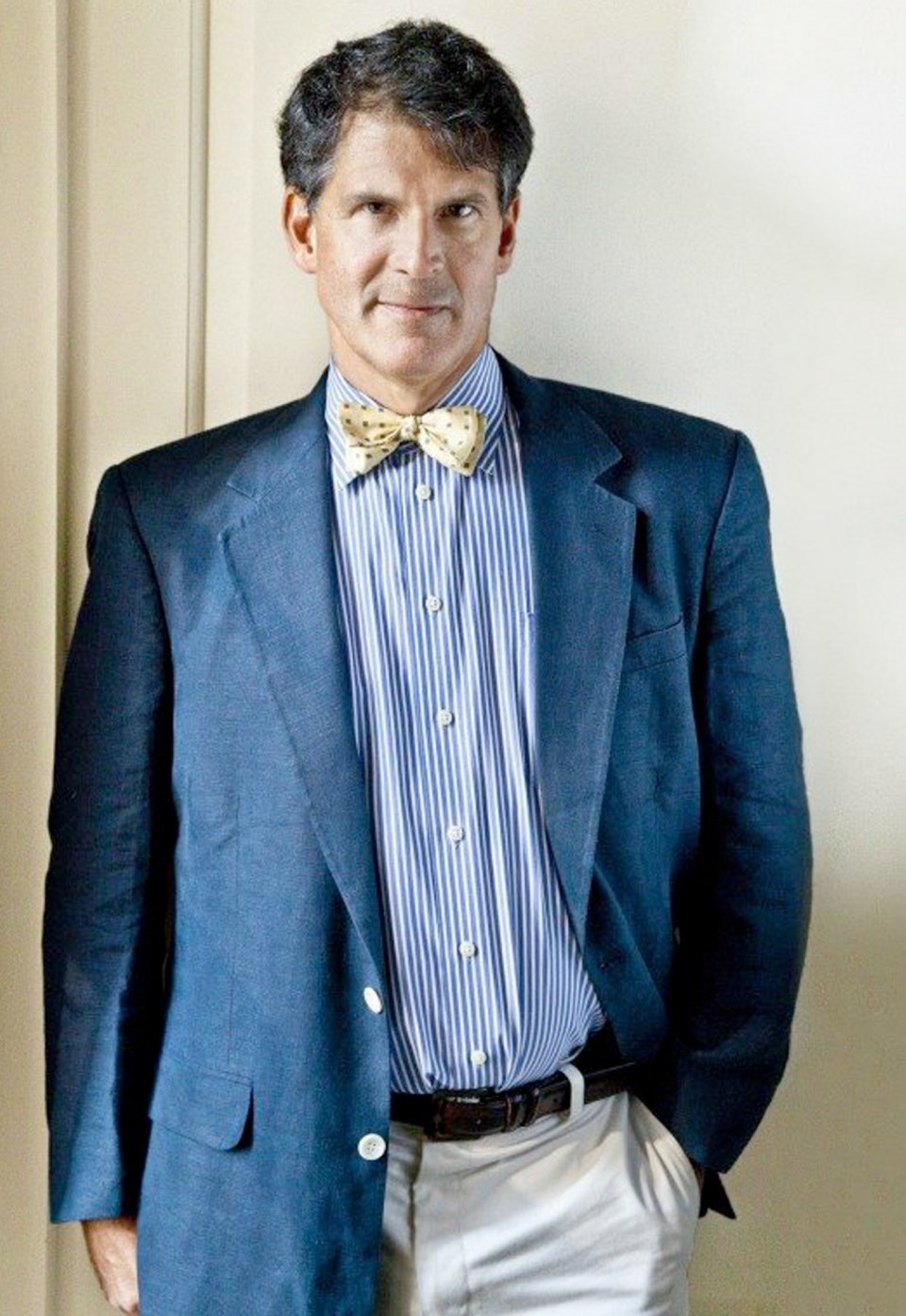

Neurosurgeon Eben Alexander III has been touring the United States and inspiring people since publishing Proof of Heaven in 2012. He has appeared on Oprah, Fox & Friends and on the cover of Newsweek, and his book has sold almost two million copies.

But his story recently came under fire in an in-depth investigative profile by Luke Dittrich in Esquire magazine. Dittrich, an Esquire contributing editor, says he found incorrect details in the book and uncovered malpractice lawsuits against Alexander where Alexander admitted lying to cover his mistakes.

Dittrich says this pattern of deception led him to conclude that Alexander was essentially down on his luck when he became sick and used the near-death experience to reinvent himself.

Alexander was born in Charlotte, N.C., went to the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and later Duke University’s medical school. He is a well-known neurosurgeon who has taught at Harvard Medical School. He lives in Lynchburg, Va.

He became ill with a virus in 2008 that placed him in a weeklong coma and almost killed him. During that time, Alexander said, he visited heaven and saw fantastical sights and met a being who told him he was loved.

Proof of Heaven is just one of many books about people who have had near-death experiences and say they saw heaven. The authors often tell of beautiful light, meeting dead loved ones and of the overwhelming and all-encompassing presence of God. Other well-known books include 90 Minutes in Heaven and Heaven Is for Real, which details the experience of a four-year-old child.

What makes Alexander’s account stand out from the near-death experiences of others is his background in science and neurosurgery. Alexander has said that when he first woke up, he thought his memories of heaven weren’t real. But as he applied his knowledge of the brain as a neurosurgeon, he said he finally had to accept that his experience actually happened.

Alexander said his medical records, which have not been released, show that he had no activity in his brain’s cortex at the time, making him unable to hallucinate or dream the experience — therefore it must have happened to his soul, outside of the physical realm.

But according to Dittrich in his article published this month, a doctor who treated Alexander said that he was put in a medically induced coma which he came out of multiple times, “conscious but delirious,” meaning Alexander had the brain activity needed to have hallucinated the trip to heaven.

Dittrich also shows other events in the book to be false. For example, U.S. National Weather Service data show that the rainbow Alexander claimed appeared when he woke up could not have happened.

“I think there are some extraordinary claims in that book, and they require investigation,” Dittrich said in an interview. “So that’s what I did, I investigated it.”

Alexander could not be reached for comment last week; a representative from his publisher, Simon & Schuster, said he is travelling and won’t be available for interviews until the fall. But Alexander did release a statement.

“I stand by every word in this book and have made its message the purpose of my life,” he wrote. “Esquire’s cynical article distorts the facts of my 25-year career as a neurosurgeon and is a textbook example of how unsupported assertions and cherry-picked information can be assembled at the expense of the truth.”

That’s not how Dittrich sees it.

“People buy something that’s sold to them as non-fiction called Proof of Heaven, and the account is based on a variety of things, including the professional credentials of the person who’s telling the story,” Dittrich said. “I think readers deserve to know the full story, and I don’t think that full story was presented in the book at all.”

It is Alexander’s claim of proof, rather than the telling of a subjective experience, that has frustrated critics.

Writing in the Atlantic magazine last December, Dr. Oliver Sacks, a professor of neurology at the NYU School of Medicine, said Alexander’s account didn’t prove anything. Sacks has written frequently on the functions of the brain, including, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Hallucinations, published in November.

“The one most plausible hypothesis in Dr. Alexander’s case, then, is that his [near-death experience] occurred not during his coma, but as he was surfacing from the coma and his cortex was returning to full function,” Sacks writes. “It is curious that he does not allow this obvious and natural explanation, but instead insists on a supernatural one.”

But others disagree with these criticisms.

John Bond Gillam III, Alexander’s cousin and president of the Outer Banks Relief Foundation, said he read Dittrich’s article in Esquire and understood its arguments but thinks they are wrong. Gillam said the issue of whether Alexander’s brain was conscious during the coma is just a matter of semantics.

“He has a great message, and his near-death experience brings great hope, brings peace and brings love,” he said. “I don’t know why anyone would want to negate that to prove a point.”