The festival landscape in Victoria has changed dramatically during the past 10 years, from a summer schedule full of time-worn fan favourites to one which is becoming increasingly populated by new kids on the block.

As scores of fans say goodbye this year to events such as Luminara, the latest in a series of high-profile festival casualties stretching back nearly a decade, they will welcome new events aimed at diversifying the local festival landscape.

Can a picturesque destination once dubbed the City of Festivals return to its former glory? Mike Devlin talks to the key players in the provincial capital who are attempting to put the fun back into a place some have taken to calling No Fun City.

When one of Victoria's most-loved festivals first opened it doors to the public in 1971, Charles Manson was being sentenced for mass murder, astronauts were landing on the moon and the Vietnam War was in full swing.

During its inaugural year, the Crystal Garden was home to FolkFest, a new arts and culture festival organized by the Inter-Cultural Association of Victoria. Its purpose? To fight racism and spread culture from around the world among local citizens.

The event, which by its final year in 2006 had expanded to 10 days, remains one of the mostloved and oft-talked-about events in the city's history. During its run, the festival was Victoria's oldest and largest multi-cultural arts festival.

FolkFest's success was brought about by a small group of dedicated people who grew the event from a small-scale festival in Crystal Garden to a summer staple in Centennial Square and, later, a festival capable of drawing 100,000 fans over the course of its run to Ship Point in the Inner Harbour.

But its failure was felt by nearly everyone on southern Vancouver Island, none more than taxpayers who reside within the boundaries of the capital region.

Nick Blasko, one of the city's foremost concert promoters, has vivid memories of the event, dating to when he was a child. But like so many Victoria residents, he is ready to see festivals in the region move forward, albeit with a cautious eye on the past.

"There is a changing of the guard," said Blasko, who cofounded one of the city's most popular music festivals, Rifflandia, in 2008. "Don't get me wrong. Every festival that dies in Victoria is a tragedy. But it's not a changing of the guard in terms of festival organizers, it's just a general evolution of Victoria."

The demise of FolkFest came during what was a calamitous year for local festivals.

In the early months of 2007, organizers announced that the seemingly unsinkable FolkFest would close its doors, some $200,000 in debt and the victim of its own popularity.

The decision affected another popular ICA presentation, Open Air in Centennial Square, which wrapped for good soon after. The other casualty announced that year was the Victoria Immigrant and Refugee Centre Society's Latin Caribbean Festival, which danced its last tango just shy of its 17th birthday.

All told, the loss of three major festivals robbed revellers of more than 419 performances and 71 days of programming.

Victoria Mayor Dean Fortin was not elected to office until 2008, but was a member of Victoria city council the year all three festivals went down. He remembers the pall it cast on everyone at City Hall, and is visibly proud that his council has played a role in the rebirth of many new festivals. It has led to what he believes is a revitalized downtown core.

"FolkFest was getting schizophrenic and it split. It may be gone, but like the Hydra, we grew two heads. And we have big winners on both sides."

Fortin is referring to both the big-ticket, high-profile events and family-friendly, low-cost fare that have emerged in the years since.

The City of Victoria is a major sponsor of numerous initiatives related to arts and culture, including Festival Investment Grants.

The 26 organizations which received city funding in 2011 through the program include the producers of the Victoria Fringe Festival ($12,000), the Victoria Dragon Boat Festival ($10,000) and the Victoria Film Festival ($8,000).

In 2009, the city also contributed a combined total of $821,000 to the Capital Regional District's Arts Development Grant Program, which funds 32 community arts and cultural organizations.

According to Fortin, the City of Victoria is the only level of government in the capital region that hasn't cut its funding to arts during the past three years.

"The arts and cultural activity [is] a reflection of our culture and our history. They help bring people together and speak to our quality of life. And they are an economic generator, so it was quite concerning when the federal government and the provincial government cut their funding through grants to the arts. It's nice to see the province and feds starting to consider coming back and reinvesting in the arts, but we've always been there for the arts community and will continue to be."

Whenever a festival goes black, the cause - according to event producers - is often a lack of funding. Because there's only so much money to go around, money is indeed an issue. But according to James Lamb, manager of the CRD arts development service, a municipal funding body with contributions from eight of the 13 municipalities in the CRD, the annual funding for festivals depends on the quality of events being presented.

"I think it's a question of hitting the right notes and hitting the right scale," he said. "Running a festival or an arts organization is like running any kind of business proposition, really. You have to know your market. If you're going to launch something, you have to launch something on a scale that's appropriate."

Musician Oliver Swain, artistic director of the FolkWest festival, was well aware of this going into his inaugural event, which is slated for Aug. 19-21 at Royal Athletic Park.

FolkWest, at its foundation, is a grassroots event. In fact, Swain said, everyone involved is a volunteer, even the executives. Making the festival volunteer-run was key to keeping the costs down, and will ensure that the new three-day event - which is being held in an underused, somewhat unfamiliar venue to concertgoers - is a success right out of the gate.

"We knew that what we were going to have to do was a slow community build from the ground up," said Swain, who reckons he has played at more than 100 folk festivals over his musical career.

To help fund the festival, the non-profit organization behind FolkWest, the Lower Island Folkfest Society, staged four fundraising concerts over a two-year period. Large amounts of corporate sponsorship weren't a good fit for FolkWest, and with no track record with which to stake a solid claim, Swain said grant money from the City of Victoria was modest.

The majority of funding for the event will have to come from ticket sales. As such, the focus has always been on producing an event of the highest quality. Swain feels if they build it properly, people will come.

"We feel like this is an important event for the community.

Yearly gatherings where we can celebrate what is going on but also invite people from around the world to come and share with us, that's an important part of a good, healthy arts community."

Part of Victoria city council's move toward a more vibrant downtown core, Fortin said, was the reexamination of Royal Athletic Park as a multi-purpose venue.

Typically used as a sports stadium, the park was has been home to a number of concerts over the years, including appearances nearly two decades ago by the Beach Boys, America, the Jeff Healey Band, the Barenaked Ladies and Colin James.

Aside from the annual Great Canadian Beer Festival, which put 7,000 people in the park over its two-day run last year, cultural events have been limited.

That all changed when the cityrun venue lost in early 2010 one of its major clients and revenue generators, the Victoria Seals professional baseball team.

This summer, Royal Athletic Park is not only playing host to big-screen broadcasts of the Vancouver Canucks' playoff run, but two of the biggest festivals in the city, FolkWest and Rifflandia, as well.

"One thing we noticed this year was that we got more requests, for sport use as well as festival use," said Terri Askham, manager of the city's culture, sport and neighbourhoods department, which is responsible for running Royal Athletic Park.

"It is primarily a sports field for community use, but we are happy to see the park alive. Anything that can work, we like to see it work."

When Rifflandia, now in its fourth year, wanted to include a large venue that would complement its downtown club presence, Blasko envisioned a move to Royal Athletic Park as a best-case scenario. When he discovered that it could hold upwards of 7,000 fans for concerts, he was ecstatic.

The transition from dream to reality, however, has required considerable homework for Blasko and his team, including meetings with concerned neighbourhood associations in the area. Blasko and Co. were successful in their bid, in part because of a self-imposed curfew of 9 p.m. on each of Rifflandia's three nights.

"We're not going to 11 or 12 at night, so they can look beyond that and understand that this is a great, fun event for everyone and enriches the city," he said.

Kimberli Persley, who works for Amelia Artists Inc., the artist management company Blasko coowns with Piers Henwood, is also on the board of the neighbourhoood association for North Park, where she lives. The area houses both Royal Athletic Park and Save-on-Foods Memorial Centre.

At a series of community meetings, Rifflandia organizers recognized the concerns of nearby residents and addressed them, Persley said.

"As a neighbourhood, we want to encourage vibrancy and encourage people to use the facilities.

We're happy to have people use them for what they are useful for. We just want to make sure when people are coming to and from these places they are being respectful."

Despite a newfound mindset at City Hall, not every festival finds downtown a viable place in which to stage an event.

Last year, the annual Victoria Electronic Music Festival, which drew close to 18,000 attendees, its highest audience total to date, became a hot-button issue when Victoria police made nine arrests (some for underage drinking) at or nearby the Centennial Square event.

Jason Guille, general manager of the festival, said the Victoria Police Department had concerns over what was perceived to be gaps in the festival's security infrastructure. "We thought that it got really blown out of proportion," Guille said.

The festival, once delivered free of charge, is now being asked to gate its site, a cost which will require patrons to pay an honorarium of a few dollars upon entering, Guille said.

"The spirit of this festival is that it's free, but the reality is that that doesn't work. It's not a step we're keen to take, in terms of our vision for the culture of the festival. It's a huge shift in our model. The fencing alone and additional required police presence, which we pay for, is a significant cost."

Some festival organizers have made the decision to move either away from the downtown core or outside the city altogether. And for the most part, these events are getting by without funding from the city or corporate sponsors.

The second annual Tall Tree Festival, a privately-funded event, is being staged later this month in Port Renfrew.

Another privately funded event, the inaugural Rock of the Woods festival, is set for late August on hundreds of hectares in Bamberton, just south of Mill Bay.

Next week, the Vancouver Island Cultural Festival is settling into St. Ann's Academy (a national historic site on Humboldt Street set among heritage gardens and orchard) for a one-day run of strictly local food, wine and music.

"I have always wanted to be able to put an injection of life back into the city without having to rely on public or government funding.

Plan it and produce it like it's a business," said Dylan Willows, co-producer of V.I.C. Fest.

"Festivals I have attended in the past that are run that way are run properly, because you have people with a serious, vested interest in that product. Our goal here is to establish this as an annual event.

I've seen so many attempts fail because people don't have their ducks in a row."

Even those with their ducks in a row can fall prey to extraneous factors, from finicky festival-goers to tenant-landlord disagreements.

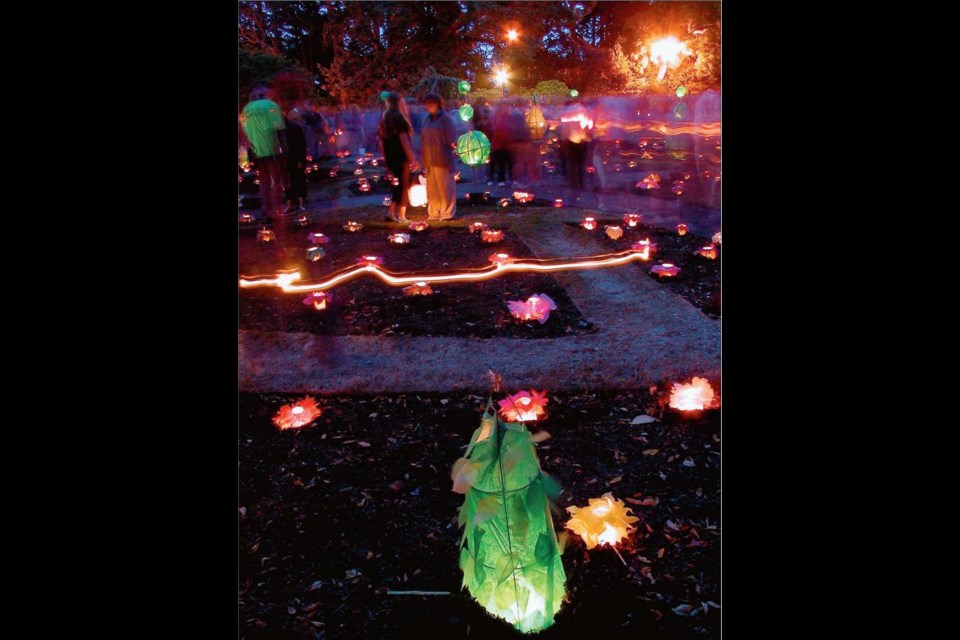

The Inter-Cultural Association of Victoria pulled the plug on the Luminara lantern festival in March, after 11 years, citing a lack of arts funding.

The Sooke River Bluegrass Festival Society wrote on its website that while last year's edition was one of its most successful to date, the festival would not go ahead on account of "increased demands from the venue's owner."

With regards to the festival turnover on southern Vancouver Island, optimists would point to the circle of life. For every festival that dies, another one - such as the inaugural Victoria International Buskers Festival - sprouts up in its place.

And for each event forced to count its nickels to survive, a number of well-run annual events - such as the Victoria Ska Festival, Fringe Theatre Festival, or the new leader, in terms of seniority, the 27th annual TD Victoria JazzFest International - do business as usual.

The amount of activity in the Garden City each summer has Fortin excited about the future.

"How we ever got the moniker No Fun City I'm not sure," Fortin said. "This is a crazy town. We've got a lot of young people. It's not your grandma's Victoria anymore." [email protected]