Letitia Ellen (Nellie) McClung might be the most well-known person resting in Royal Oak Burial Park.

McClung is the leading candidate to become the first Canadian-born woman to grace our currency, and women throughout Canada are better off because of her efforts a century ago.

With that in mind, let’s consider the contributions of some of the women buried or cremated at Royal Oak.

There are artists, authors, politicians, business leaders and many others. This summary only scratches the surface.

McClung was a writer who fought for women’s rights and for the temperance movement. She is one of the Famous Five women who pursued the Persons Case, which established that women must be recognized as full persons under the law.

There are Famous Five monuments in Calgary and Ottawa. A branch of the Greater Victoria Public Library bears McClung’s name.

Also in Royal Oak is Sarah Annie “Nancy” Hodges, the first female Speaker of the legislature in British Columbia — and in the British Commonwealth.

Hodges was social editor of the Victoria Daily Times from 1916 to 1943. She argued that more women should enter politics, and was elected to the legislature as a Liberal in 1941. She was named Speaker in 1950, but lost her seat in 1952.

She joined the Senate in 1953, and resigned from it in 1965. She died in 1969.

Elizabeth Forbes, whose grave marker is just a few metres from that of Hodges, succeeded Hodges as social editor at the Times. Forbes, who died in 1981, was the author of Wild Roses at Their Feet, the story of Vancouver Island’s pioneer women.

Annie de Bertrand Lugrin Shaw, who died in 1962, wrote Pioneer Women of Vancouver Island under the name N. de Bertrand Lugrin. It was a groundbreaking book, telling of strong women in a predominantly white community setting.

Monica Mary Hughes, a children’s author, died in 2003. Her works won the Canada Council’s Children’s Literature Prize and the Phoenix Award.

Lynn M. Jackson, also known as Sparkle the Clown, entertained children and adults for 30 years with original music, magic shows and balloon artistry. She died in 2012 and is at rest in the Woodlands area, a natural burial section.

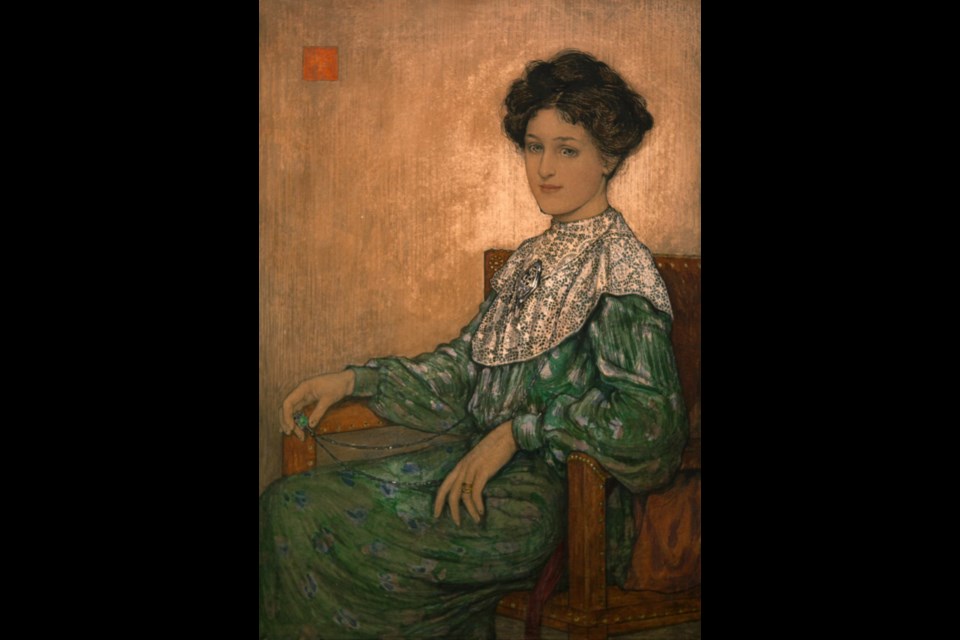

Also at Royal Oak is Edythe May Hembroff-Schleicher, who was an artist, and a friend and biographer of painter Emily Carr. She died in 1994. Two of her paintings are in the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria collection. Under the signature of Edythe Hembroff Brand, her Portrait of Emily is in the Vancouver Art Gallery’s permanent collection.

Katharine Emma Maltwood, who died in 1961, was an artist who moved to Victoria in 1938. She and her husband John bought a large home on West Saanich Road. She was well known for her sketches and sculptures, knew Emily Carr and Ina Uhthoff, and wrote several books.

In 1964, three years after her death, John Maltwood turned their home and its collections over to the University of Victoria. The university ran it as a museum until 1975, when it was closed. The former Maltwood home is now the Fireside Grill restaurant.

Pierrette Alarie-Simoneau, an opera singer, died in 2011. She made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1945 and spent three seasons singing there. In 1946 she married Léopold Simoneau, an acclaimed tenor. They worked together in Europe for several years, including at major festivals and opera houses.

Eileen Elizabeth Dailly, who died in 2011, started her career teaching eight grades at once, in a one-room school on Denman Island, and ended up as the education minister in Dave Barrett’s New Democratic Party government from 1972 to 1975.

She banned the strap at public and private schools, made kindergarten mandatory and stopped provincial exams.

Laura Holland was the first professional social worker in British Columbia. She died in 1956.

In 1927 she reorganized the child-care program of the Vancouver Children’s Aid Society, directing the transformation from institutional to foster-family care. In 1930, she helped start the School of Social Work at the University of British Columbia.

Eleanor Hope Shackleton, who died in 1960, worked as a nurse for half a century, in England, Greece, France, the United States and Canada and in war zones.

She moved to Victoria in 1944 and retired in 1959 after spending 56 years caring for others. Her efforts were overshadowed by those of her brother, the Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton.

Marguerite Ethel Spratt took over Victoria Machinery Depot in 1921 when her husband, Charles Joseph Vancouver Spratt, became ill. She ran the company until her death in 1946.

Victoria Machinery Depot was one of the largest industrial companies on Vancouver Island. Spratt kept VMD alive through the Depression years, and then coped with the increase in shipbuilding orders that came with the Second World War.

When she died, her will specified that her house, at 548 Lotbiniere Ave., could not be sold while her dog Rip was alive. Rip and his housekeeper remained in the house until he died in 1949.

Dianne Hall-Carruthers, who died in 1995, rose through the ranks at Alberta Gas Trunk Line, and was named a senior vice-president in 1978.

Hall left the oil industry in 1987 and moved to the coast, where she owned and operated Sea Island Air with her husband, Bob Carruthers.

Two garden legends were cremated at Royal Oak. The ashes of Princess Peggy Abkhazi were scattered on the grounds of her garden in Fairfield, while the ashes of Jennie Foster Butchart were scattered in Tod Inlet.

Lydia Augusta Arsens was elected to the legislature in the Social Credit victory of 1953, becoming the only female MLA in the house.

Arsens said, among other things, that doctors were ignoring a known cure for cancer, that fluoridation of water was bad and that people were being poisoned by the food they ate. In the legislature, she argued against the consumption of coffee and tea, and attacked candy shaped like cigarettes, cigars and pipes. Arsens died in 1983.

Eliza Goodson, a former slave, was considered to be Canada’s oldest citizen when she died at 107 years of age in 1932. Merle Emeline Barwis had been Canada’s oldest person for almost two years when she died in 2014 at 113.

Jennie Elizabeth Mostyn-Hoops, who died in 1925, was a pioneer in Victoria — arriving in the gold rush year of 1858 — and in the Cariboo region.

In 1873, when she was 19, Jennie married Peter Curran Dunlevy, who had been given credit for starting the Cariboo gold rush with his strike in June 1859. Together they operated hotels, stores and a farm.

After Peter died in 1904, Jennie assumed full ownership of his businesses. In 1906, she married Samuel Evans Mostyn-Hoops, a medical doctor.

Another Cariboo pioneer was Julia Apnaut, who was taken to Barkerville as a baby. Both of her parents died when she was young, and her mother’s family took her to Maple Ridge, where she lived with the local First Nations, learning their language, customs and songs. Many years later, she recorded the songs for the British Columbia Archives. She died in 1952.

Apnaut’s grave is close to that of Émilie Lagrois, who is considered to be the first woman to climb the Chilkoot Pass, and the first white woman in the Yukon.

Lagrois and her first husband, Pierre Nolasque Tremblay, worked gold claims until 1913, when they moved to Dawson. After Tremblay died in 1935, she married Louis Lagrois. In 1985, the first francophone school in the Yukon was named École Émilie Tremblay.

Mabel Helen Driscoll, a native of Winnipeg, was 23 years old when she boarded the Titanic for its maiden voyage to North America. Her father and brother died when the ship sank, but Mabel survived, and died in 1968.

Margaretta Gray Watson helped the cemetery get through the darkest days of the Great Depression, with several financial contributions after the death of her husband John in 1931.

Watson provided money for a drinking fountain, shrubs, a greenhouse and the first official office building. Watson died in 1938, but the Watson fund remained on the books until the late 1970s.

Finally, Doris Charnock Thomson Gravlin was beaten and strangled by her estranged husband, Victor Richard Gravlin, in 1936. Her husband hid her body on the Victoria Golf Club links, and then committed suicide by drowning.

There have been several reports that she is still with us — in spirit form, at least. She has been seen on the golf course, as well as on Beach Drive, adjacent to the course. She is usually wearing a white dress or brown business attire.

Taken from Dave Obee’s book Royal Oak Burial Park: A History and Guide. The second edition of this book will be available at the Summer So(u)lstice at Royal Oak Burial Park on Saturday, June 25.

The event, which will feature live music and poetry, will be held from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. at the cemetery, 4673 Falaise Dr. in Saanich.