When the white folks arrived, they mistakenly called the place Nootka, and then Friendly Cove. It was actually the village of Yuquot on the far west coast of Vancouver Island.

When the white folks arrived, they mistakenly called the place Nootka, and then Friendly Cove. It was actually the village of Yuquot on the far west coast of Vancouver Island.

Art Gallery of Greater Victoria curator Haema Sivanesen herself is relatively new to the West Coast, and she decided that this “point of contact” would be a good place for her to focus on. Working on the Nootka theme, she gathered prints by Nuu-chah-nulth artists, engravings by British explorers, artwork by Emily Carr and J.W.G. Macdonald, a video by Stan Douglas and an installation by a contemporary artist from Tofino, Hjalmer Wenstob.

Nootka is a good theme for an exhibit, but I wish there were more work on show, and that more background material were provided. A map would have been helpful. When I came home, I was inspired to do my own research and discover what happened at Nootka.

The Nuu-chah-nulth people have been happy and healthy on this spot for at least 4,300 years. As the gallery doesn’t collect native art specifically, the First Nations are here represented by six fine old cedar-bark weavings by Nuu-chah-nulth women and six screen prints from Art Thompson, Patrick Amos and Tim Paul. Most of this was provided by the University of Victoria’s University Art Collections.

The story changed when the Spanish sailed into Friendly Cove in 1774. They would have starved and died without the hospitality of the locals. According to the Mowachaht people, they came in “floating houses rigged with sails, starving, sickly, pale, womanless men, spirits perhaps, in any case disinherited beings who lived on the water and had nowhere else to go.”

In 1778, Capt. James Cook came by and discovered the luxurious sea-otter fur and opened trade at Nootka. By 1788, the British built a trading post there. The Spanish hoped to solidify their own trading interests on the coast and in 1789 they also built a fort at Friendly Cove. Both were concerned about the Russians, who were also trading in sea-otter pelts. Just at this time, the French and the American revolutions were redrawing alliances all over Europe, and the Spanish were at war with Britain.

It was at Nootka that Capt. George Vancouver of Britain and Capt. Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra of Spain met in 1792 to settle global matters. During a respectful meeting, these enemies decided to name this island “Vancouver and Quadra’s Island.” But Spain’s colonial empire was in decline, and in 1795 they dismantled their fort and left. Then, within a few years, the fur hunters trading with China had nearly wiped out the sea otters, and Nootka faded back into the mist.

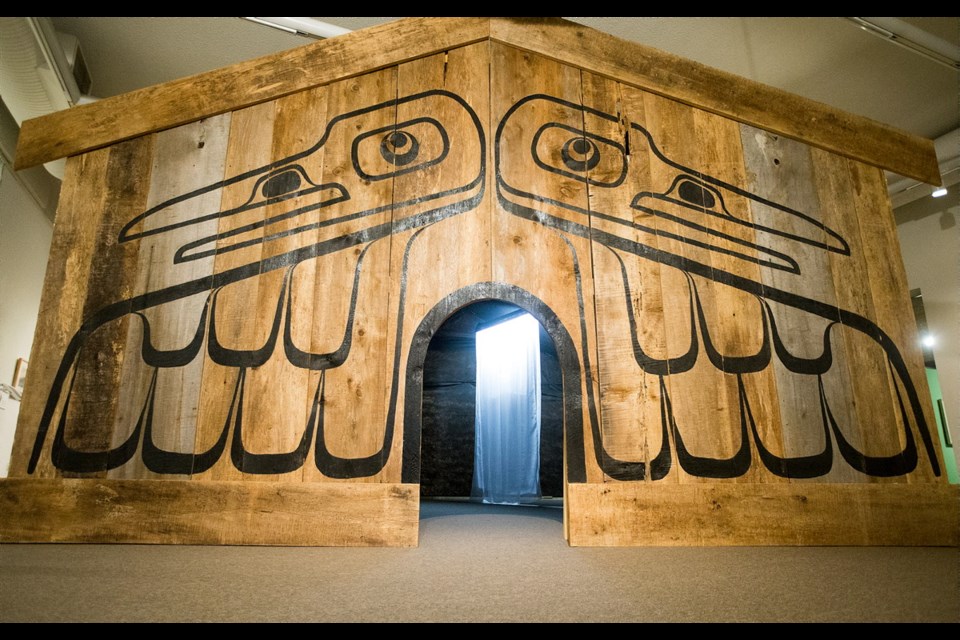

In the exhibition at the gallery, Hjalmer Wenstob, a young Nuu-chah-nulth artist, set up his portable “big house,” which holds six roughly carved planks. These refer to the “Whalers’ Washing House,” a secret place of purification rituals for Nootka men who went out to sea in canoes.

The original was a small building holding 88 carved human figures, four carved whales and 16 human skulls. It was “collected” in 1904 by George Hunt, acting on the instructions from Franz Boas, and since that time has languished in storage at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. This pre-eminent anthropological ensemble is a major focus of the repatriation movement, but its return is not addressed in the current show.

In fact, Wenstob’s “big house” is a surprisingly spartan affair, perhaps a reference to the poverty that remained at Nootka after Boas took what he wanted. I learned online that this installation was part of Wenstob’s recent MFA project at UVic.

Emily Carr went by ship to Friendly Cove in May 1929, but she refused to visit the marker commemorating Capt. Cook’s arrival in 1778.

“Tourists, how I hate them,” she complained. “They spent most of the time at the Nootka monument with their cameras. … I stayed and talked to the old Indians who were friendly and interesting. How beastly superior the white race are. I don’t wonder the Indians despise us.”

While there, Carr painted totems, and sketched the iconic white church, but that painting was not available. Returning to Victoria, Carr made a series of large charcoal drawings of the forest, influenced by Mark Tobey and Lawren Harris and, perhaps, Haida argillite. One of these is on show.

On loan from the Vancouver Art Gallery are three oil paintings by Jock Macdonald. Arriving from Glasgow, Macdonald taught with Fred Varley at the new Vancouver School of Art from 1926 to 1933. When the Depression hit the school in 1933, Varley and Macdonald walked out and started their own art school. That soon failed, and in 1935, Macdonald escaped with his family and a couple of artist friends to Nootka. He managed to make a few paintings there, but didn’t last long in the face of the elements, and returned to Vancouver the next year.

For this show, one entire gallery has become a screening room for Stan Douglas’s video Nu.tka (1996). On screen, two videos of the shoreline at Nootka are interwoven and, as they merge, two men read conflicting dialogues at the same time. This voiceover is largely incomprehensible. Douglas is a highly regarded Canadian artist, but I find this video annoying.

The Art Gallery of Greater Victoria awaits funds for its planned renovation, and long-range exhibition planning seems to be on hold. Point of Contact is based on a good idea, but has not been fully realized in the current installation.

Point of Contact at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1040 Moss St., 250-384-4171, aggv.bc.ca, until April 1.