Political correctness, the careful vetting of speech or written language to remove sexism and racism, has long been condemned as a left-wing form of stifling censorship.

Mostly conservative pundits and leaders from Charlton Heston to George Bush (the elder) and talk-radio host Rush Limbaugh to Canadian TV commentator Ezra Levant have all bemoaned it as intellectual fascism and an affront to free speech.

“Political correctness is tyranny with a happy face,” Heston is quoted as saying.

But an American university study published in the Administrative Science Quarterly suggests political correctness actually boosts creative productivity, at least within mixed-sex groups.

The study’s authors, from the universities of California, Berkeley, Cornell, Vanderbilt and Washington, say their evidence suggests creativity is unleashed when political correctness is observed, and that the observance of political correctness does not cause people to filter out or withhold valuable ideas.

Instead, political correctness makes clear what is appropriate behaviour and encourages creativity by removing social uncertainty from members of a group, the authors say.

The results challenge the “widespread assumption” that true creativity must involve a kind of social anarchy where everyone can say whatever they think, no matter the consequences, they say.

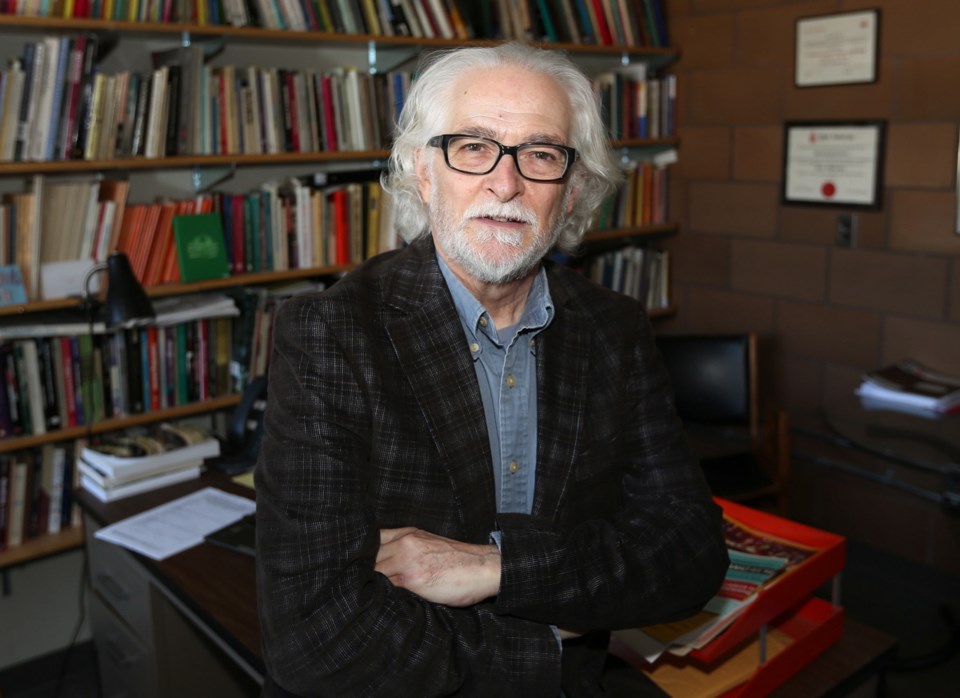

William Carroll, professor of sociology at the University of Victoria with a special interest in social movements, said he was not entirely surprised by the study’s findings.

Carroll characterized political correctness as trying to avoid harming people by weeding out sexist or racist language. Installing it as a group ethos would build a culture of mutual respect, in which nobody is excluded.

“So co-workers are put on a more equal footing, vis-a-vis each other, and they can develop mutual respect and that can foster really effective teamwork,” he said in an interview.

Carroll traces the push for political correctness back to the 1960s and ’70s. Feminism and movements advocating civil rights, the rights of migrant workers and, in Canada especially, the rights of First Nations have all played a part.

“All these movements have contributed to a kind of social and political ethos where it is increasingly recognized that language matters and we should be using respectful language,” Carroll said.

He said notable objections to political correctness arose from intellectual libertarianism, which holds that freedom of speech is an absolute right that must not be tampered with in a free society.

The other common source of objection is right-wing populists such as the Tea Party movement in the U.S.

Canada, said Carroll, with its anti-hate laws and a few widely publicized anti-hate court cases, has not seen the same level of opposition.

He said political correctness has mostly influenced society on the individual level, but left broad social inequalities in place.

So women, for example, are given more respect in the workplace. But they are still kept out of career advancement by the lack of affordable child care.

Governments make “symbolic” apologies to First Nations people for past wrongs, such as the residential school system. Yet First Nations people are still among the poorest Canadians.

“What [political correctness] addresses are the micro-level interactions between people, say in the workplace, but not the structural conditions that can reinforce existing inequities,” he said.

The American study divided participants into same-sex and mixed-sex groups. Control groups were not exposed to any politically correct behaviour or language, while the others were exposed to it and asked to discuss it among themselves.

All groups were then asked to brainstorm ideas for a new business to be housed in the site of a failed restaurant, a task with no right or wrong answer.

The mixed-sex group exposed to political correctness generated a higher number of ideas than the mixed-sex control group. Same-sex groups generated fewer ideas.