The Saanich First Nation people have a word for success gained after much struggle: le, nonet (pronounced le-non-git). It means “paddling a canoe in a storm and making it through to the other side.” For many Canadian aboriginal youth, a college certificate or university degree is still an unreachable shore.

Slightly less than half (48.4 per cent) of all aboriginal people in Canada, age 25 to 64, have a post-secondary certificate or degree, according to the 2011 Census of Canada. That’s compared with 64.7 per cent of non-aboriginal Canadians.

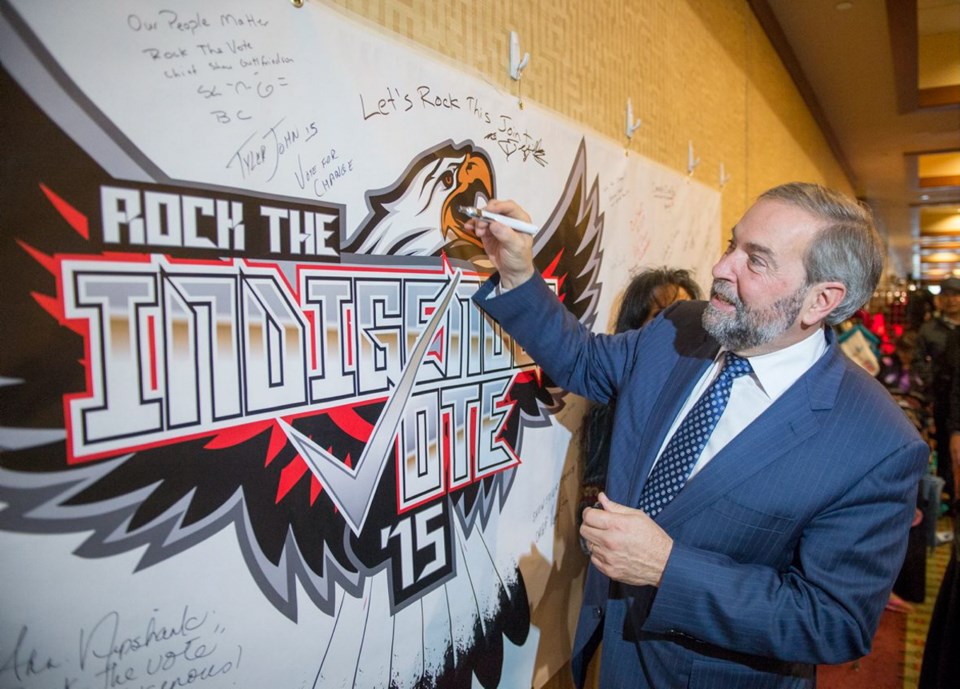

Throughout this election we have been talking about issues that matter to young Canadians. A recent visit to the University of Victoria got us thinking about how to remove the obstacles to post-secondary education for First Nations, Metis and Inuit youth.

With so many aboriginal people living in poverty, tuition cost is an even greater challenge than for non-aboriginal students. The Assembly of First Nations says that, even with federal government support, most bands don’t have the finances to assist all their students in need.

UVic offers tuition bursaries for aboriginal students, and an innovative University of Winnipeg program rewards local aboriginal high school students for their academic achievements and community service with credits towards their eventual tuition.

But scholarships are only half of the solution. The lingering inter-generational trauma of residential schools has left many leery of education. It’s difficult for aboriginal youth to envision a future for themselves that includes college or university, according to Ruth Young, director of the UVic’s Office of Indigenous Affairs.

That’s why Canada needs to invest resources earlier on. We were fascinated by the range of non-scholarship aboriginal support services offered by UVic and others. The university’s Campus Cousins outreach program, for example, helps aboriginal youth in primary and secondary school examine their life goals to see if a post-secondary education is a good fit for them. UVic also runs a week-long “mini university” summer camp for youth in grades eight to 12 to encourage them to consider post-secondary education.

Challenges remain when aboriginal students get to college or university. Imagine what it must feel like when you’ve lived your whole life on a remote reserve, suddenly finding yourself on a teeming campus where your culture is not represented in the faces around you, or the course material you study.

Culture shock contributes to higher dropout rates among aboriginal students. So schools must also create welcoming and supportive campus and course environments.

Good examples include Ryerson University’s aboriginal peer support program, and UVic’s and Nipissing University’s aboriginal-mentoring programs, counselling services, and aboriginal cultural centres. Both of the latter universities have also recruited First Nations elders on their staff and faculty. Young says some departments at UVic are removing Eurocentric biases from curriculum to better reflect aboriginal history and culture. Ryerson, in Toronto, runs an aboriginal peer support program.

Research appears to back the effectiveness of these initiatives. UVic’s aboriginal support programs have led to a 20 per cent increase in the graduation rate of aboriginal students and a 67 per cent reduction in dropout rates, according to a study by the Canadian Millennium Scholarship Foundation.

But what we notice is that all these efforts are largely scattershot. Young agrees that colleges and universities should collaborate and learn from one another.

We see an opportunity for the Canadian government to bring colleges and universities together and encourage them to develop aboriginal student support programs on more campuses. Aboriginal students deserve to have as many choices for welcoming institutions within a reasonable distance, with programs that interest them, as non-aboriginal students do.

Time and again we hear from aboriginal leaders that education is key to overcoming myriad and complex challenges facing Canada’s indigenous peoples. While the focus must remain on equal access to quality primary and secondary education, we can’t ignore post-secondary.

Higher education transforms aboriginal youth into role models and contributors to their communities, inspiring the youth who follow them to achieve their own “le, nonet.”

Brothers Craig and Marc Kielburger founded a platform for social change that includes the international charity Free The Children, the social enterprise Me to We and the youth empowerment movement We Day. Visit we.org for more information.