Every time he goes to his car, the keychain with the Molson beer logo reminds Mark Lijek of that astounding rescue, 32 years ago in revolutionary Iran, that has now become Ben Affleck's hit movie Argo.

On Jan. 28, 1980, he and his wife were among a group of six Americans from the overrun U.S. Embassy who were given new identities by the CIA. They became Canadian filmmakers who had been scouting locations for a movie.

With their new IDs, they then strolled past the customs check at the Tehran airport in a ruse that even today sounds quite unbelievable.

But it really did happen. The story of how a fake movie was used in the rescue remained classified by the CIA for 17 years; instead, a sanitized version was presented. The story was made public only for the agency's 50thanniversary celebration in 1997.

"One of the things about that experience," says Lijek, "is that when I'm in a situation I feel I can't deal with, or something looks like it's too big a problem, I think back to those days. Hey, I say, if you can get out of Iran, you can deal with this."

The keychain for the Canadian beer was part of the ruse, just as when the Americans were given quick lessons in Canadian speaking mannerisms, like using "ehh?" and saying "aboot" for "about."

That all was the work of Tony Mendez, the agent who at that time was chief of a CIA branch described as having "operational responsibility worldwide for disguise, false documentation and forensic monitoring of questioned documents." In the movie, Affleck plays the part of Mendez.

Back in 1980, Lijek, a Seattle Prep graduate, was 28 and in the Foreign Service, and Tehran was his first assignment.

His wife, Cora Amburn-Lijek, was 25 and also worked at the U.S. Embassy, in the visa section. They had been married four years, after meeting when they were studying at Georgetown University.

These days, Lijek, 61, retired, is on the phone a lot - a reporter from Rome is calling, another from Detroit, and the list goes on.

He and Cora recently added some new material to their scrapbook about their Iran adventure.

It contains such items as the personal letter that President Jimmy Carter sent to Mark's parents that ends with, "Together our prayers and actions will speed the day of their return."

Among the new additions are memories of the Oct. 4 opening screening of Argo at the Sam Goldwyn Theater in Beverly Hills, California.

The studio had a limo pick up the couple in Anacortes, flew them to Los Angeles and put them up in a suite at the Four Seasons.

"He seems like a really nice guy. Down to earth," says Cora about Affleck.

Just like in Affleck's movie, it helps to give a little background about Iran in those days. Three decades is a long time ago.

The crisis began Nov. 4, 1979, when Iranians stormed the U.S.

Embassy in Tehran and took 52 Americans hostage.

They were not released until 444 days later. Their long ordeal helped doom Carter's presidency.

But besides those 52 hostages, six Americans working at the embassy managed to slip by the Iranian mob and ended up hiding in two homes of Canadian diplomats.

On the day the embassy compound was overrun, Lijek at first thought this was yet another demonstration, like others before, "that had gotten out of hand."

But then the courtyard door was bashed in with steel bars.

Glass was broken on a second-floor restroom, and somebody was climbing a ladder placed against the wall.

In an e-book that Lijek has written, The Houseguests: A Memoir of Canadian Courage and CIA Sorcery, he tells of staffers smashing intricately designed visa plates that used special inks to stamp tourist visas so they couldn't be forged.

The 52 hostages who were taken had been mostly in the chancery building. The Lijeks and a few others were in the nearby consular building.

They walked out past Iranian officers who didn't pay much attention to them.

For the next few days, the small group of Americans moved to different sites. It was the Canadians who came through for them.

Two of the group stayed at the home of the Canadian ambassador, Ken Taylor. The others stayed at the home of John Sheardown, a Canadian immigration officer.

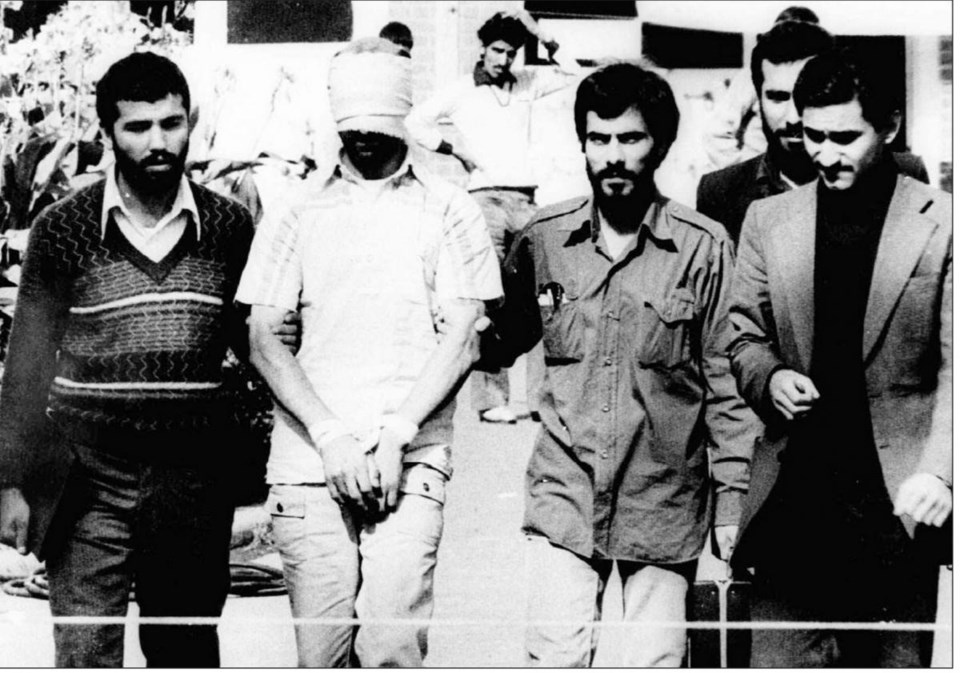

In their 11 weeks of hiding, the Argo Six never experienced imprisonment, beatings, being paraded blindfolded or threatened with execution, as the embassy hostages did.

At the 20-room Sheardown home, "the pantry seemed inexhaustible." Cigarettes were bought for them on the black market. There was liquor.

Lijek read a lot of books - 57 of them. The group listened to the BBC or Voice of America on a shortwave radio.

They also played Scrabble, so much so that it was mentioned in news stories after their rescue and the manufacturer sent each of them a deluxe version of the game, with the board on a swivel.

The couple still uses that souvenir board.

But the Americans couldn't keep staying with the Canadians.

At some point, the Iranians would figure out there were Americans unaccounted for. "And what if one of us became ill and required hospitalization?" says Lijek.

Enter Tony Mendez. In a paper that's published on the CIA's website, he describes how he went about the "exfiltration" of the Argo Six.

The Canadians had agreed to provide passports on humanitarian grounds.

The Iranians needed cash that a movie would bring, and they were looking to promote tourism, Mendez reasoned, giving them an incentive to co-operate with a film production.

With his Hollywood contacts from previous deceptions, Mendez created a film-production company. He placed full-page ads in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter that principal photography would soon commence for Argo, a film about "a cosmic conflagration."

It looked so authentic, Mendez wrote in his CIA paper, that by the time the film-production company folded after the rescue, it had received 26 scripts. "One was from Steven Spielberg."

The name "Argo," Mendez wrote, had been the dirty punch line to a knock-knock joke, and also happened to be the name of the ship sailed by the mythical Jason and the Argonauts, perfect for this nonexistent sci-fi film with a Middle Eastern twist.

Mendez flew into Tehran on Jan. 25, 1980, on a fake Irish passport. The passports for the Argo Six, along with such items as the Molson key chain, Canadian flag-lapel pins and business cards, would arrive in a Canadian diplomatic pouch.

Over two days, Mendez went over their cover stories. Lijek was a transportation co-ordinator; his wife was the scriptwriter.

In case they were interrogated at the airport, they had to have their stories down pat - their new names, dates of birth.

They were told to make themselves look like Hollywood types.

Lijek did his best to grow a beard - "it was a ratty beard, so Tony put mascara on it."

Cora used sponge curlers "so I looked liked Shirley Temple." And Mendez gave her makeup sticks to help alter her features. She worried that having dealt with numerous Iranians applying for visas at the embassy, someone might recognize her. Nobody did.

The group arrived at the airport at 5 in the morning, booked on a Swissair flight to Zurich, Switzerland. There were some tense moments, such as when they were showing their passports at the departure lounge.

Lijek remembers standing at the counter when "a sleepy-eyed man emerged carrying a teapot" and stamped their passports.

The movie version is considerably more dramatic, with Iranians chasing the Swissair jet in a car.

Lijek doesn't mind. "It's authenticity versus accuracy," he says.

"Authenticity has to do with mood, atmosphere. The reality is that most of what could have gone wrong, didn't."

Lijek is well aware that Argo, which as of last week was No. 1 at the box office and has brought in more than $63 million, likely wouldn't have had this success if it had been about those 52 hostages.

The latter did return to a ticker-tape parade and were showered with gifts, including lifetime passes to any major-or minor-league baseball game.

But as one of the hostages told The Washington Post years later about having to strip naked and face a mock execution by the Iranians: "How does someone ever forget that? Life was uncertain after that."

For the Argo Six, there are no such horrible memories.

Says Lijek: "Our story was a big adventure with a happy ending. You can't say that about the hostages, unfortunately."