A giant faux boulder dominates the cavernous space inside suburban Albany's newest climbing gym, a whale of a rock with twenty somethings often clinging to its undersides, straining to mount the five-metre-high lip through subtle balanced moves and brute strength.

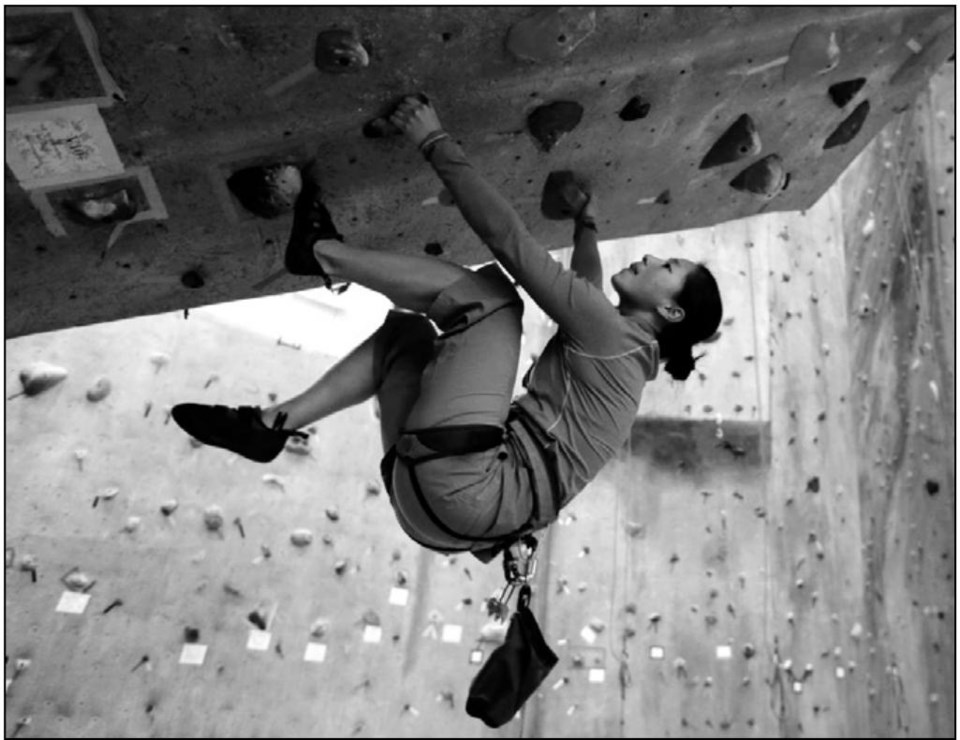

As often as not, climbers drop off the bumpy surfaces of the pale blue boulder. They sometimes fall on their backs onto 30-centimetre-thick foam or more often get stuck, dangle from handholds, then drop to their feet, rubbing tight forearms and studying the so-called "problem" for another attempt. Others "top out," then walk across it to the easy, stepped descent at the back.

The design and weeknight crowd at the Edge Halfmoon climbing centre reflect two big trends in climbing: toward indoor gyms and low-elevation challenges that don't require a safety rope. The gym logged about 10,000 visitors its first year, including kids at birthday parties, a few old mountaineers keeping their hand in and many gym athletes, several on a youth team.

"I think once you start improving, that's when you get hooked," Helen Ho said after making a half-dozen athletic moves beneath the boulder's 60-degree-angle overhang before dropping off. Soon she was carefully working her way up a separate vertical problem that required a series of graceful, flexible movements, shifting her weight from one small foothold to another, nearly requiring a split, hips pressed to the wall, hands gripping only "slopers."

Those roundish protrusions were spaced along the way, difficult to hold firmly.

"Nice," her two friends said when she reached the top and walked off. All three were Albany Medical College students. Ho started climbing as an undergraduate at a Houston gym five years ago. Now 26, she also climbs outdoor cliffs with her boyfriend, who has the rope and hardware needed.

She compared bouldering to sprinting, noting that its many hard problems can be discouraging at first, and wall climbing to distance running, requiring more endurance. She does both, and she said climbing has made her stronger and capable of putting her body in positions she couldn't before.

As for the boulder,

"Sometimes we'll choose to use it as a warm-up. Other times we'll just go there and try to do a few problems," said Joyce Lu, who learned to climb indoors as an undergraduate at UCLA. "It's more conducive if you're with a group, because then you can, like, cheer each other on and stuff."

On many weeknights, the main action is on the boulder, with most climbers ranging in age from about 16 to 35. The gym's 40-foot blue and yellow walls tend to attract older enthusiasts, especially those who started in the outdoors when bouldering was only something you did to warm up and the few indoor walls were cob-bled together in back rooms for off-season training. The loose accordion of five walls, with about 100 climbing routes, also gets busy, with everyone clipped to safety ropes.

"Of the 10,000 people that have been here, I'd say maybe two per cent have been outdoors," manager Adam Catalano said. "Ten or 15 years ago, there were maybe five [commercial] gyms in the country. Now there's hundreds."

Catalano helped build the Edge as a project for Youth for Christ and included the public when he opened its doors last year. He himself started with traditional rock climbing and spent 10 years running outdoor trips for kids. After a gym they frequented in nearby Schenectady lost its lease and closed, the non-profit built this one.

The giant boulder was added in recognition of recent trends: 3,000 square feet of climbing surface with about 70 alternative problems to solve to reach the top. Those square feet are paying the mortgage and utility bills, he said.

Surveys by the Outdoor Foundation, an affiliate of the trade group the Outdoor Industry Association, showed nearly 4.1 million youths and adults went indoor climbing, bouldering or sport climbing in 2011.

That compared with about 1.6 million Americans who went ice climbing, mountaineering or traditional rock climbing outdoors.

"I think it is two worlds," said Tom Rosecrans, a long-time climbing guide and owner of the RockSport climbing gym in Queensbury, New York, near the southern edge of the Adirondacks. "A lot of them will never put a rope on."

There is crossover, of course, but bouldering is more athletic and dynamic and less expensive, said Cort Gariepy, chief executive of Rockwerx in Barre, Massachusetts, who designed the boulder and climbing walls for the Edge with Catalano's input.

"It's much more accessible than traditional climbing. There's much less gear involved. It's less dangerous. It's just much more accessible to the general public," Gariepy said. "In fact, when I get together with my old climbing cronies, they blame me for having ruined the sport."