With calls to remove statues of controversial figures such as Sir John A. Macdonald, the University of Victoria is putting on a series of lectures about the historical characters in the news. Four historians are presenting brief “warts and all” biographies of four historical figures in the news: John A. Macdonald, Joseph W. Trutch, Matthew Baillie Begbie and James Douglas and putting them in their historical context to help inform public discussion. Each talk will be followed by a discussion on such questions as “how should we remember these characters and their contexts?” and/or “to commemorate or not commemorate?” Hamar Foster will speak about Matthew Begbie on Wednesday. All talks will take place in Council Chambers, City Hall, 1 Centennial Square, Victoria, 7-8:30 p.m.

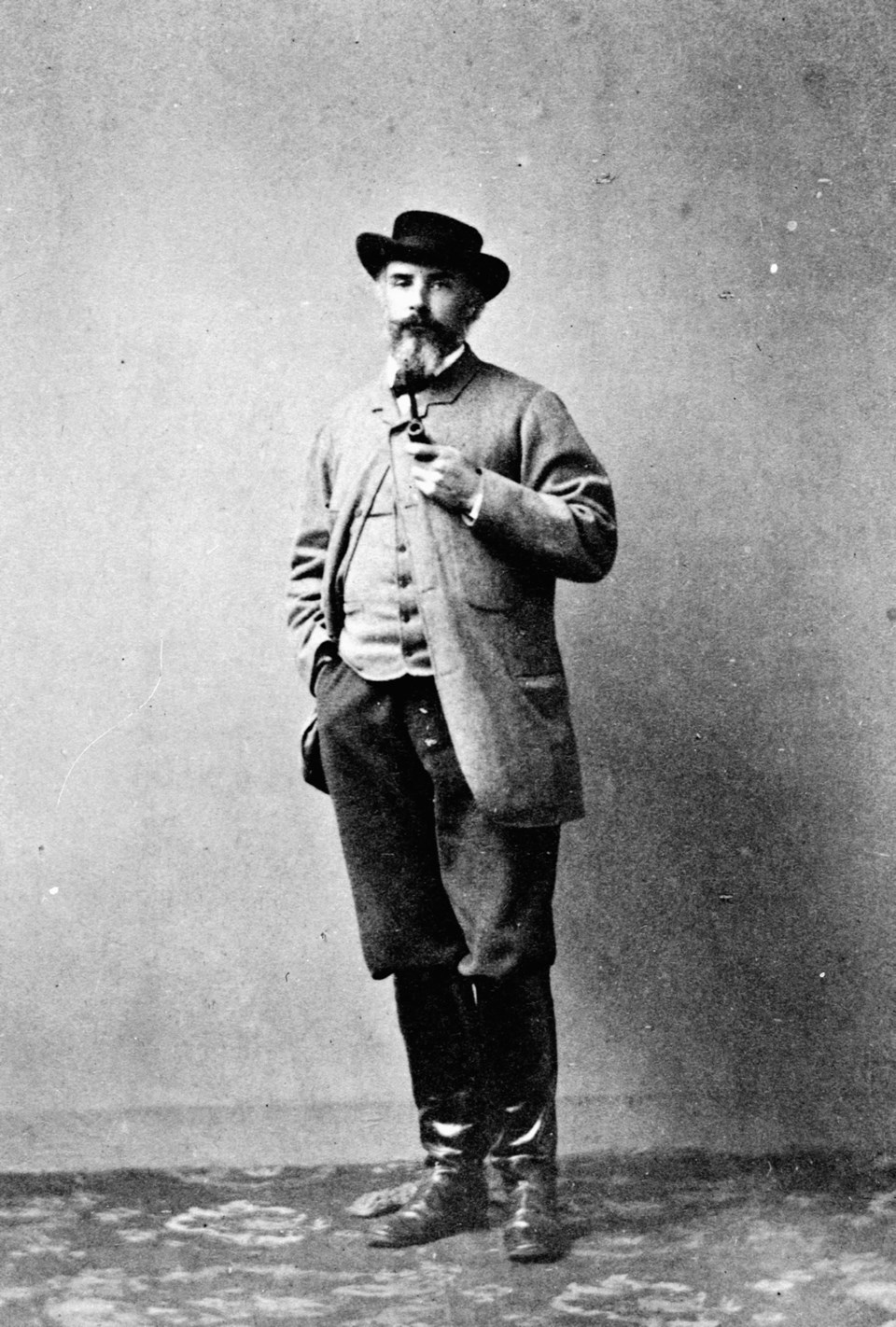

Matthew Begbie was the colony of B.C.’s first judge from 1858-71 and the province’s first chief justice from 1871-1894. He held court in almost every settlement, often under trees or in tents.

In 1865 alone, he covered about 5,600 kilometres on foot, on horseback and by canoe. In the Stikine country in 1879, the year he turned 60, his party lived mainly off the land, “eating rabbits, grouse and squirrels, most of which Begbie himself shot.” He loved the outdoors, and is a hero to lovers of Beacon Hill Park for his ruling in 1884 preserving it from development.

But the so-called “Hanging Judge” was controversial almost from the moment he stepped off the boat in 1858.

In 1860, Governor James Douglas had to deal with complaints that Begbie had allowed a white man to be convicted of assault at Yale “wholly on testimony from Indians.” That same year, he was accused of writing a pamphlet that expertly skewered the political hopes of one of the candidates for the Vancouver Island legislature (the man for whom the City of Langford is named).

Begbie denied any involvement, which would have been improper (even though his jurisdiction was confined to the mainland colony at the time). He also maintained that every charge in the pamphlet was true. But, as his biographer put it, the Colonial Office was unconvinced and, in effect, told him: “Don’t do it again.”

Begbie’s denunciations of juries for reaching verdicts he did not like also attracted criticism. On one occasion, he even called a jury a “pack of Dalles horse thieves” for convicting a murderer only of manslaughter, adding that he would like to see them all hanged for it. But in his report to the governor, he advised that the verdict was “not perhaps an altogether unsatisfactory result.” It seems at least some of his harsh comments were theatre, designed to emphasize that the rule of law would be enforced in B.C.

Such outbursts and other, less inflammatory, pronouncements all contributed to the legend. At one of his first trials, he told the assembled miners that in the U.S. they might govern “by the Bowie knife and the Colt’s pistol,” but not in British Columbia. Here, he said, we “have a law which prohibits the carrying and use of offensive weapons. … Let me tell those who are in court, as well as those outside, that any who carry such weapons will be dealt with to the full limit of the law.” It is not clear that there really was such a law, but the point — and his reputation — was made.

Begbie’s decisions were effectively unappealable during the colonial period, which would have made almost any judge more autocratic than a judge should be. Indeed, his anger and less than judicious behaviour in two cases in New Westminster in 1862 were such that, years later, he apologized. Responding in 1876 to that city’s congratulations on his knighthood, he said he had done things he was sorry for in those cases and asked their forgiveness — an act of judicial contrition unusual even today.

Begbie was also controversial for his racial attitudes, telling a royal commission in 1884 that the “four prominent qualities” of the Chinese were “industry, economy, sobriety and law abidingness.” And that, he said, was the main reason they were unpopular. The Daily British Colonist (now the Times Colonist) criticized him for this, maintaining that the Chinese were “hereditarily on a lower plane of civilization.”

In the ensuing years, Begbie continued to condemn “racial jealousy” and set aside convictions under discriminatory bylaws dealing with such matters as licences for Chinese laundries and pawnshops whenever these issues came before him. A century before Canada adopted its Charter of Rights, he described such laws as an infringement “at once of personal liberty, and of the equality of all men before the law, and also a negation of international rights.” On his last circuit in 1889, when he was 71, he renewed old acquaintances in the Cariboo, describing the Chinese who had been there since the gold rush 30 years earlier as “better British Columbians than nine-10ths of the later arrivals.”

Other decisions also raised eyebrows. In 1889, he overturned the conviction of a man who had pleaded guilty to potlatching, holding that the law against it was too vague and unfair to support lawful convictions. This rendered the potlatch ban a “dead letter” until, after Begbie’s death, Parliament strengthened it.

His positive opinion of B.C.’s Indigenous Peoples, formed early on, did not change. Nor did his very British class-consciousness: “My impression of the Indian population is, that they have far more natural intelligence, honesty and good manners, than the lowest class — say the agricultural or mining population — of any European country I have ever visited, England included.” On another occasion, he described them as “a race of laborious independent workers.”

Begbie also protected the territorial integrity of the Songhees Reserve in a case that illustrated his belief that, if at all possible, justice should trump legal technicalities. He was a skilled lawyer and judge, but as he put it himself, camping on the hard ground and coping with an overturned canoe were more important in the new colony than a sound knowledge of “Fearne’s Contingent Remainders or … the Rule in Shelly’s Case.”

Unlike most of his contemporaries, Begbie was fluent in several languages, including the Chinook jargon, and made a concerted effort to learn some of B.C.’s Indigenous languages (although I doubt he was as proficient as some of his admirers contend).

Was he a “Hanging Judge”? Where he had discretion, he could certainly impose a harsh sentence if he thought it was justified. But he had no discretion in capital cases: When the jury convicted someone of murder — and all such trials in Begbie’s court were jury trials — the death penalty was mandatory. However, he could recommend for or against death, or remain neutral.

Fifty-two men were charged with murder between 1859 and 1872. Of these, 38 were convicted. Begbie recommended clemency or remained neutral in 18 of these convictions, or almost half. His biographer could find no evidence that he was described as a hanging judge in his lifetime, and, ironically, Begbie never considered a career in the military because he “found it abhorrent to take human life.”

Begbie is also controversial today for his role in the trial of the Tsilhqot’in who made war on the mainland colony in 1864. The evidence strongly suggests that they were tricked into surrendering, and the jury convicted five of the six notwithstanding that they had meant “war, not murder.” The death penalty was automatic.

In his report on the trial to the governor, Begbie said that it “seems horrible to hang five men at once — especially under the circumstances of the capitulation. Yet the blood of 21 whites calls for retribution.” He added that he was glad the decision was not his to make.

Both levels of government have since exonerated the executed men, and the Law Society of British Columbia has removed Begbie’s statue from the foyer of its building, citing his role in the Tsilhqot’in trials.

What would Begbie have thought of this? His instructions to his executors were that “no other monument than a wooden cross be erected on my grave, that there be no flowers and no inscription but my name, dates of birth and death and ‘Lord be Merciful to Me a Sinner.’ ”

Hamar Foster, QC, is a professor emeritus at the University of Victoria.