Abstracta Delecta: The Quebec Painters at Winchester Galleries (winchestergalleriesltd.com, 2260 Oak Bay Ave., until May 28).

Abstracta Delecta: The Quebec Painters at Winchester Galleries (winchestergalleriesltd.com, 2260 Oak Bay Ave., until May 28).

The Winchester Galleries have opened a major survey of abstract paintings from Quebec, dating from the 1950s to the present.

This show includes all the big names, some surprisingly big paintings, and among the highest prices ever seen in a Victoria art gallery. This is carefully selected work from the repertoire and estates of 16 of the most highly regarded painters in our art history.

The gallery is to be congratulated for years of effort and acumen that have brought this show together, working with the senior artists and their estates. It’s the sort of thing our art institutions should be doing, but seem to lack the time and interest.

The art of Quebec is a distinct subset of Canadian art. After the Second World War, the society there, dominated by the Catholic church and the traditionalist government of Maurice Duplessis, was under pressure to move into the modern world.

The St. Lawrence Seaway was shifting the centre of gravity of Canada away from Montreal. The CBC and National Film Board gave creative people a voice of their own. Québécois artists, trained in dialectic in Catholic colleges and influenced by the existentialist philosophers of France, wrote out their demands in manifestos such as the famous Refus Global, published by Paul-Émile Borduas in 1948.

The art of Quebec that developed during that time was more like the art of Europe than the free-spirited style being set loose in America. It was said that the European artist was nostalgic for the ancient forms, and dwelt in self-pity over the loss. The American, on the other hand, was a barbarian, playing out the story of the rugged individual in a new land. Consider the coloured geometries of the European Victor Vasarely, compared to the cowboy bravado of Jackson Pollock and his drips.

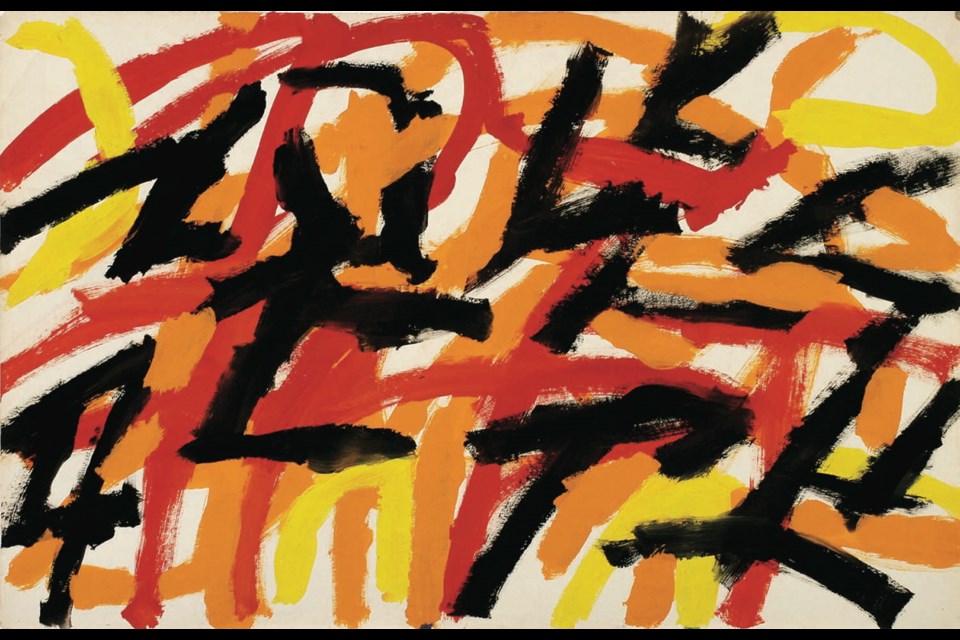

The earliest pieces in the Winchester show were painted according to a principle of automatism — mark-making that was believed to well up from the unconscious. This automatic painting — Molinari even painted blindfolded at one point — was part of the surrealist movement. There is no image. The purity of intent, its authenticity, was everything.

This early phase of Quebec abstraction is here represented by engaging small works by each of the illuminati in their early years: Borduas’ watercolour from 1950, and others by Riopelle 1953, McEwen 1954, Tousignant 1955 and Molinari 1958.

The idea of paint-as-paint (and not as a picture of anything) was treated in a more heroic and personalized idiom in the 1960s, with the paintings of Hurtubise 1963, and Lise Gervais 1962 and 1964. These were akin to the heroic American mode called abstract expressionism, which dominated Toronto’s art scene.

As modernism progressed in Quebec, ever larger canvases were constructed, carrying larger and simpler forms. Claude Tousignant’s “colour field” piece titled Luxe, Calme et Volupté is almost two metres square, with a single broad form of burgundy and grape tones squeegeed across a white canvas. Nearby, the even larger feathery screens of colour brushed by Jean McEwen have a dispersed power.

The Quebec spirit always leaned toward the intellectual European manner, more concerned with form than personal gesture. Geometric abstraction allowed the artists to inscribe intense and simple images that were not autographic marks of the brush. In this type of painting, the precise calculation of hue and tone is essential.

Tousignant’s red and green target named Petit Oeil is an ideal example, eventually leading to the minimalism of Yves Gaucher, and monochrome panels of uninflected colour. Before you leap up and shout “that’s not painting,” have a look at the real thing.

These colours are sublime. Gaucher is here represented by four paintings, including his famous VI 1986, which is three metres across. Around the margins of this field of simple haunting grey, slightly darker strips dart about in my peripheral vision. Another of his, displayed downstairs at Winchester, is four metres across. Clearly, a larger gallery is necessary if they are going to continue in this way.

But, as they do, things fell apart. Jean-Paul Riopelle was the greatest star of the movement, a bright young man who in the 1950s took his promise to Paris, and painted up a storm using a palette knife and multiple slashes of unblended pigments. He was one of the only artists of this group to be taken on by a big New York gallery and sold on the world stage.

Some of those paintings are kaleidoscopically wonderful, the most expensive of all Canadian art. Of that sort of early work, only one tiny piece from 1953 is in the show.

But Riopelle continued, evolving and doing his own thing. The three late works in this show, created in 1990, are remarkable for their audacity — the artist was not simply replaying his greatest hits. But what are we to make of a background of spray paint over chains, overlaid with gawky awkward birds drizzled onto the plywood with sparkle paint? It’s a good thing Riopelle has such a fine reputation to trade on.

After the Quebec artists reached the monochrome minimalism, there was nowhere to go but off into the ether of conceptualism and, with it, the end of painting — though the artists worked on. This exhibition presents the passage through abstraction here seen in its finest and most intellectually rigorous Canadian manifestation: the abstract painters of Quebec.

Go for the visual thrills, stay for a lesson in Canadian art history and, as you leave, consider the simple pleasure of seeing the most expensive paintings ever offered in Victoria. A full-colour catalogue accompanies the show, but even the best reproductions only hint at the effect of the actual works.