The town named after him has disappeared, his name on the burial records was misread and his grave site was nearly lost as a result.

But the memory of Peter Leech and the formation of Leechtown, near Sooke, will be marked today at Ross Bay Cemetery. B.C. Lt.-Gov. Judith Guichon will lay a wreath on his new and burnished headstone at 2 p.m.

Today’s date and ceremony will mark the 150th anniversary of the discovery in 1864 of gold near the junction of the Sooke and Leech rivers. It was a find that kicked off a short-lived gold rush to the area.

And on Saturday, Guichon will be a guest of the Vancouver Island Placer Miner’s Association near the site of Leechtown in the Capital Regional District’s Kapoor Park, where a new plaque is planned to pay homage to the memory of the gold rush.

The Leech River gold rush was one of the first economic jolts to what was, at the time, a British colony. It also offered a good show of the further economic promise of Vancouver Island.

And it provided confirmation of the promise of all British Columbia, a name chosen in 1858 by Queen Victoria. Mainland B.C. and Vancouver Island wouldn’t be joined until 1866.

Lee Boyko, executive director of the Sooke Region Museum, said Peter Leech and the discovery of gold in the river named after him are best viewed in historical context.

“It gave people the belief that there was more to be found in the area, and it attracted more people,” Boyko said. “It just added to the evidence to convince people there were things to discover.”

But the real story of Peter Leech, born in Dublin in 1826, the river that still bears his name and the gold discovery for which history has given him credit — even today’s ceremony — can be traced to historical happenstance.

Leech was in the right place; somebody else wasn’t. He was forgotten and somebody rediscovered his whereabouts.

According to The Gold Will Speak for Itself: Peter Leech and Leechtown, Victoria’s Goldrush, by Victoria author Dr. Patrick Lydon, Leech died in 1899 and was buried in Ross Bay Cemetery.

But much later, his name, handwritten into the original burial register, was misread as “Peter Luck.”

Once the incorrect name, Luck, had been entered into the official record, Leech’s resting place almost vanished. Even the marker stone, inscribed with the single word “Leech” was lost, overgrown with moss.

But in 2009, historical investigators deduced the error. A replaced and readable stone now marks the graves of Leech and his wife, Mary MacDonald, 1837-1892.

It’s known Leech joined the British army in Ireland and was posted to the Royal Engineers, where he trained as a surveyor.

He was sent to the Crimea to serve in the conflict with Russia and when that ended his regiment was posted to Fort Langley, near New Westminster. The regiment disbanded there in 1863.

But rather than take the army’s offer of a trip back to Ireland, Leech chose to settle in the colony. A year later, he joined what was being called the Vancouver Island Exploratory Expedition as a lieutenant and second in command.

The expedition landed and moved inland from Cowichan Bay beginning in June 1864 and reached the Sooke River the following month.

At this point, the most obvious happenstance occurred to put Leech’s name into the records. Dr. Robert Brown, a botanist from Edinburgh and the commander of the expedition, returned to Victoria for supplies, leaving Leech in charge.

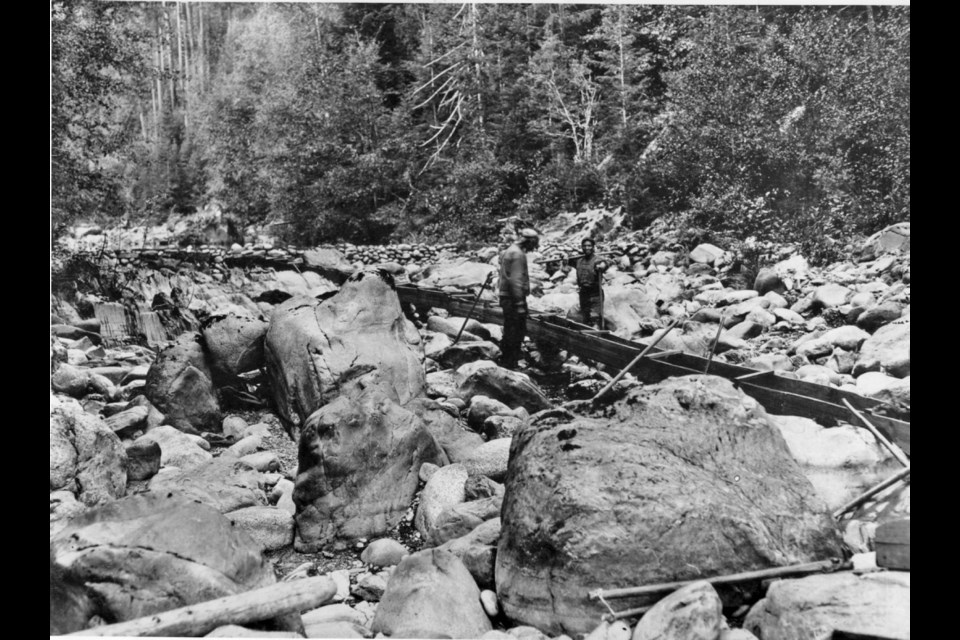

Expedition members started exploring a then-unnamed river flowing into the Sooke River and discovered gold. With Leech in charge at that moment, the river was named after him.

Weeks later, a progress report was sent to the colonial governor of Vancouver Island: “The gold will speak for itself.”

But some insist it was Brown who authored and sent the message from Cowichan Bay, where he had been joined by Leech.

And others point out it was really an expedition member, miner John Foley, who discovered the gold while Leech was elsewhere surveying the landscape.

“There are some people who feel [Leech] gets bigger credit than he deserves,” Boyko said.

Donna Chaytor, of the Vancouver Island Placer Miner’s Association, said even the name “Leechtown” wasn’t used until some time in the 20th century, well after the gold rush was over and Leech had died.

“I have the greatest respect for Peter Leech and think he was a fine man,” Chaytor said. “But to me he didn’t touch a piece of gold and he didn’t find a piece of gold.”

According to Lydon’s book, Leech didn’t even profit from the discovery. Nevertheless, he had many adventures and otherwise lived “an exemplary life in the new world and should be recognized as a pioneer.”

Leech was later part of an unsuccessful expedition to lay a telegraph cable from B.C. through the Yukon, Alaska, Russia and into Europe. Later, after a number of government and commercial appointments around B.C., he was made Victoria city surveyor, a job he held until he retired.

His wife was organist at the Church of Our Lord and a beautiful and popular member of Victoria society. Mary MacDonald had arrived in Victoria in 1862 with her widowed mother and four sisters aboard a brideship, loaded with women to be prospective wives for colonists.

The Leeches’ own daughter, Fanny, grew up to be a well-known and popular musical prodigy and was a friend of artist Emily Carr.

News of the gold find had been electric right from the start. Before 1864 was over, six general stores were operating in the area. About 1,200 miners had arrived and were supplied by 30 saloons. By 1865, most of the easily accessible gold was gone.

Lumbering, however, became a source of enterprise. The railway arrived. Merchants came; importers and builders and tradesmen set up shop. Southern Vancouver Island began to develop.

Leechtown is gone, although it hung on for few decades. Around the middle of the 20th century, the last inhabitants departed or died.

But Leechtown and the brief gold rush can’t be dismissed, whoever’s name is attached.

“It gave people a lot of dreams,” Chaytor said. “People came, some lost their shirts and others decided to stay.”

“It just started up the whole thing of commerce on Vancouver Island.” she said.

Chaytor’s research leads her to believe the name of Leechtown and the veneration of Peter Leech himself began with another happenstance.

In 1928, a commemorative rock cairn was erected to mark the site of Leechtown. It has long since been destroyed by vandals. But when it was unveiled, it happened Leech’s daughter, the popular Fanny, was in attendance and she needed to be acknowledged, even at expense of historical accuracy regarding her father.

Chaytor said her research has led her to believe Leech would have been a little uncomfortable about all the veneration of his name.

“From what I’ve come to know of the man, I think he would be embarrassed,” she said. “He wasn’t a braggart and I don’t believe he ever packaged himself as the man who found the gold.”