This is part four of a six-part series, exclusive to the Times Colonist, that examines the role of the provincial government in the uprooting, detention, dispossession and exile of Japanese Canadians, 1941-1949.

Perhaps no other issue clearly reveals the callousness of the B.C. government in regard to Japanese Canadians than its maltreatment of the community’s children.

It began the day after Pearl Harbor, when B.C. superintendent of education S.J. Willis ordered all Japanese language schools shut down on authority of the Council of Public Education, a cabinet agency.

On the basis of a single complaint about Japanese Canadian kids in Duncan schools, B.C. education minister H.G. Perry then ordered school inspectors to undertake a province-wide investigation, indelibly marking Japanese Canadian students in the public school system.

Ironically, A.S. Christie, trustee and chair of the Victoria School Board’s education committee, reported “that there had been no signs of anti-Japanese feeling in Victoria’s schools, and such tolerance is a credit alike to the white and Japanese pupils.”

Seventy-six Japanese Canadian students attended public schools in Victoria alone, and boys in Grade 6 and above had been participating in cadet training. That was not to last, however.

On Feb. 20, 1942, Perry introduced a provincial order-in-council stating it was “not deemed advisable under existing circumstances that any student of Japanese racial origin be allowed to wear the uniform of a school Cadet Corps,” and therefore that “no such student be allowed to enrol in a Cadet Corps or to wear a cadet uniform in the Public Schools of the Province.”

Similarly, the University of British Columbia expelled Japanese Canadians enrolled in the Canadian Officers Training Corps.

The uprooting that took place in April 1942 saw children torn from schools up and down the coast. The late Dr. Michiko (Midge) Ayukawa recalled: “I am 12 years old and should be back at Strathcona School. One day, restless and bewildered, I went for a walk with my six-year-old brother. We went to my school and sat on a low fence and I stared at the window from which my Grade 7 teacher had often looked outside. I ‘willed’ her to spot me and perhaps wave a greeting; but to my disappointment, she didn’t.”

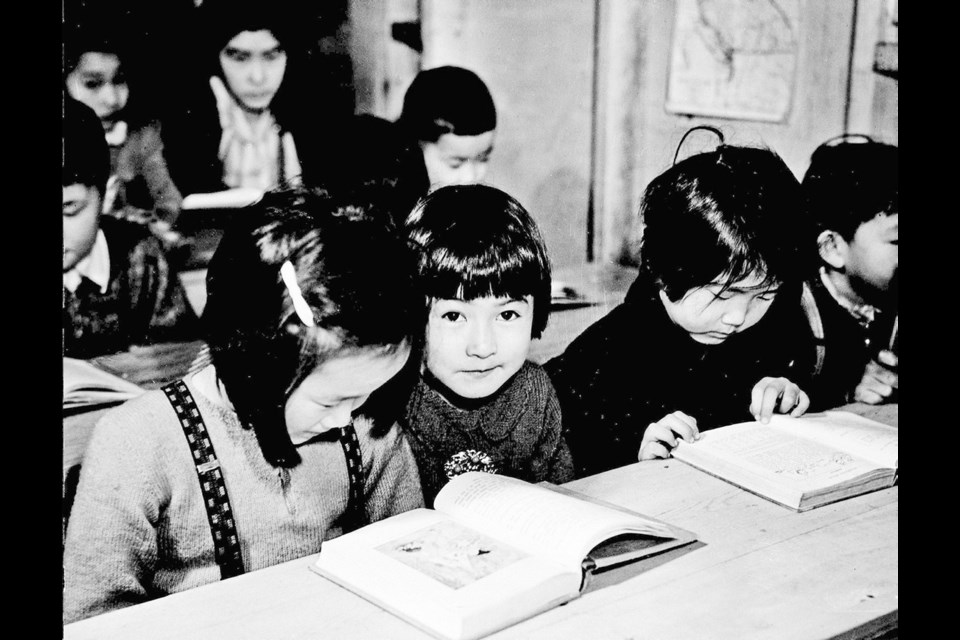

Shunted into detention camps, Midge Ayukawa and hundreds of other youngsters faced an uncertain future. Barred from public schools, families scrambled to provide some sort of schooling.

In early 1943, the B.C. government had announced legislation that would exempt the province and local governments from providing education for Japanese Canadian youth in the camps.

The New Canadian, the only journal published by Japanese Canadians during the war, responded: “The British Columbia Provincial Government should continue to bear its share in educational costs, just as it had been doing for over 40 years before Pearl Harbor, and in accordance with its constitutional responsibility.”

Matters came to a head after Humphrey Mitchell, the federal labour minister, learned of the “unqualified refusal of the Government of the Province of British Columbia to assume any responsibility, either financial, or in the matter of administrative direction, in respect to the education of children of Japanese persons evacuated from the protected areas of British Columbia to other parts of the province.”

Mitchell communicated with Mackenzie King, the prime minister, who immediately cabled provincial premier John Hart. In the cable, and a longer letter that followed, King urged Hart to refrain from passing such legislation, asking for the province’s assistance in establishing courses, directing work and training of teachers.

Hart agreed to drop the legislation in return for King’s promise not to press for the province’s share of education funding, but gave no response to King’s request for provincial administrative assistance.

High school students faced even greater challenges. Because there were no qualified teachers, students could only take correspondence courses that their parents had to pay for.

Mary Keiko Kitagawa, whose family was detained in Roseberry for more than two years, recalled her older sister had to walk miles from Roseberry to New Denver to get help with her correspondence courses. The Kitagawa family scraped together the money to pay for the course — but for them and others it was an incredible hardship.

“One mother sold her sewing machine rather than ask for help to buy books for her children,” the New Canadian reported at the time.

Detained Japanese Canadians, many facing impoverishment, had to pay exorbitant fees for correspondence courses. In the legislature, CCF MLA Grace MacInnis demanded Perry explain why Japanese Canadian students had to pay nine dollars for a single course that cost others only one dollar.

Perry said it was a federal matter. Asked why he didn’t ask the federal government to cover the cost, Perry declared that letting Japanese Canadians into the schools would be “selling a birthright for a mess of potage.”

“I would be selling the whole school system for $65 a kid.” This was the yearly per capita amount the province was supposed to pay for each student enrolled.

Such “savings” allowed the province to project a budget surplus for 1942-43. Non-funding of the children’s education over the internment years amounted to an estimated $15 million (in current dollars).

The incredible story of how families came together to meet the education challenges created by the uprooting and government intransigence has been told by Frank Moritsugu and the Ghost Town Teachers Historical Society in their volume Teaching in Canadian Exile.

Volunteer teachers from the community, often young women just out of high school, stepped in to organize basic education services for elementary schools under the supervision of Hide Hyodo (Shimizu), one of the first accredited Japanese Canadian teachers in the province. Allies from churches and conscientious objectors also helped.

Communities organized to build schools and many students found school classes offered a semblance of normality. The fact that communities banded together to meet the challenge does not exonerate the provincial government for abandoning its constitutional responsibility, a fact noted in a 1944 Royal Commission:

“Your Commission finds that although education is and always has been a provincial right and obligation, the Department of Education of the Province of British Columbia has refused to take any responsibility for the education of the Japanese children in the Interior Settlements although before these same children were evacuated from the Defence area this responsibility was recognized and assumed.”

Next Week: Part 5, Dispossession

John Price is professor emeritus (History) at the University of Victoria and the author of Orienting Canada: Race, Empire and the Transpacific and, more recently, A Woman in Between: Searching for Dr. Victoria Chung (with Ningping Yu).