Peter O’Reilly landed in Victoria in early 1859 during the height of the Fraser River gold rush. Though he’d been reluctant to leave Ireland, he flourished in Canada, and played a critical role in shaping British Columbia. He made his mark as a gold commissioner, assistant land commissioner, county court judge and Indian Reserve commissioner. In her book, Kamloops author Lynne Stonier-Newman provides a glimpse into his personal life, including his relationships with other notable historic B.C. figures.

Shortly after Peter O’Reilly returned to New Westminster, he dined with Dr. Powell and Begbie, who were concerned about how depressed he was. After they had extended their sympathies over his and Carry’s losses again, Powell, still the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for British Columbia, asked, “Do you believe the joint commission will work? Or do you find it as fraught with potential problems as I do?”

When O’Reilly looked puzzled, Sir Matthew explained that Ottawa had just announced that the Joint Indian Reserve Commission for B.C., initially created the previous spring after the 1876 Indian Act had been passed, was to proceed. “The three commissioners are to begin sorting out the land and water problems between the settlers and Indians next month.”

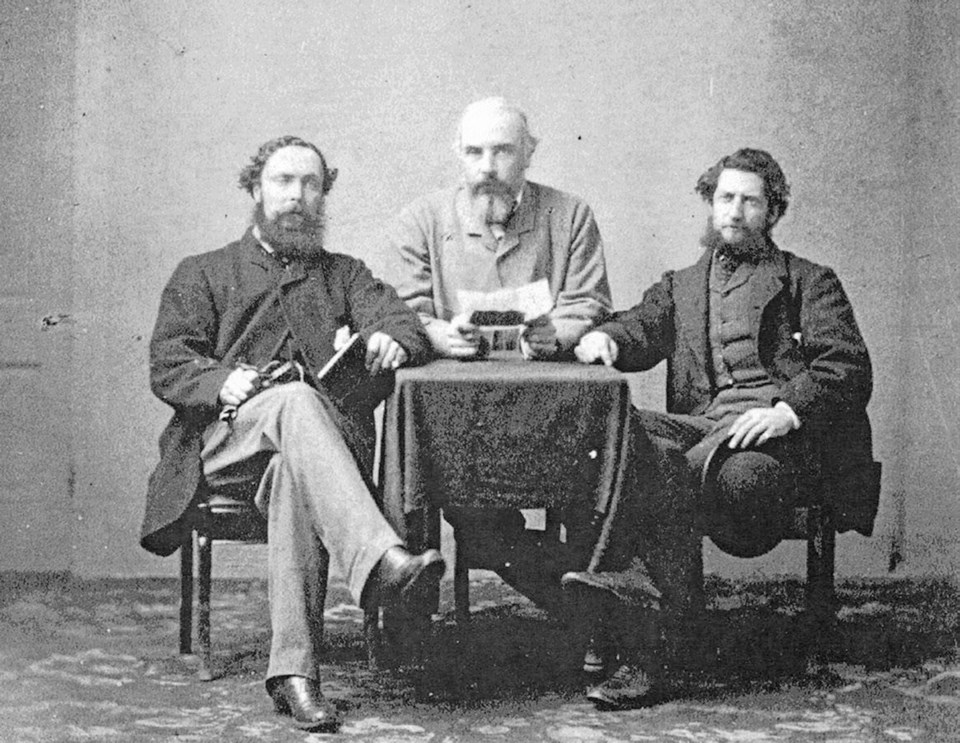

The members were A.C. Anderson, to represent Canada’s interests, and Archibald McKinley, to look after B.C.’s, while Gilbert Sproat was the joint appointee. Anderson had most recently been the federal fishery inspector for B.C. while McKinley had held several official positions in B.C. and was respected for his extensive knowledge of the Indians on both the mainland and the island. Sproat had been B.C.’s first agent-general, responsible for promoting immigration.

The commission had been stalled for months, due to a dispute between the governments of Canada and B.C. McKinley had been instructed by the B.C. government that as their representative, he was “to ensure no unnecessary large reserves were apportioned.” Canada’s government had informed the B.C. legislators that that was not feasible and they replied that the Joint Indian Reserve Commission for B.C. could not proceed until it was. The federal ministers remained adamant that the formula for acreages assigned to Indian bands in one province was to be used to size the reserves in all provinces, including B.C.

Finally, Canada’s minister of justice had issued a proclamation excluding the Indian lands and reserves in the province of B.C. from the operation of the Indian Act.

“I was sure the commission would be cancelled,” Powell admitted. “And most surprised when I received notice from Ottawa that it would begin this spring. What a change of policy! Probably it will have long-term consequences.”

“I agree,” Begbie interjected. “Allowing B.C.’s reservations to differ in size from those elsewhere in the Dominion is a fundamental revision.”

O’Reilly was astounded. “Do you mean that B.C. does not have to conform to the ‘S’ section of the Indian Act?”

“That’s correct,” Dr. Powell said. “However, the consequence is that establishing the acreages for B.C.’s reserves becomes unclear. It’s no longer shaped by Canadian law.”

Begbie forecast that the exemption for B.C. would make it challenging for the commissioners. “Although each of them is well-qualified, agreeing what to assign will create ongoing disputes.”

“It will be hard for the commissioners to function.” O’Reilly wondered whether Joe’s old ten acres per family would be used. “Maybe all the boundaries I set won’t have to be revised.”

Powell chuckled, said that he didn’t know how the reserve acreages would be set and changed the subject. He asked if either Begbie or O’Reilly had encountered James Lenihan, the Dominion government’s new census taker for B.C. Indians, who had not reported in as expected. The man had planned to begin his task somewhere in Burrard Inlet and was to record in detail how many people — adults, youth and children, male and female — lived on all the reserves. He was also to count the houses, barns, stables, cattle, oxen, horses, pigs, fowl, ploughs, harnesses, scythes and corn mills that each Indian family owned as well as to note each individual’s occupation and his or her ability to speak English.

“English? Why? What about their own languages?” Begbie asked, his annoyance showing.

Powell bristled. “Sir Matthew, I did not set the census questions. In fact, I was not informed it was under way until Lenihan came with his instruction from Ottawa.”

Begbie refilled the wine goblets. “I’m afraid the Indian situation is going to deteriorate. For instance, the Okanagan and Shuswap tribes are traditional enemies, yet I keep hearing about them meeting in large gatherings. Jointly, they would be able to drive off all us whites, at least temporarily.”

They all thought that the Dominion’s Indian Superintendent General, L.P. VanKoughnet, was ill-informed about British Columbia and had questioned whether one system could work for all of Canada’s aboriginals, as it did not factor in the differences between each area’s climate and terrain.

…Five years later…

While the women chatted, O’Reilly was working in his home office, completing the paperwork from the previous season. After Sarah left, he told Carry that he’d completed his reports for how he’d set up or revised reserves in the Cariboo, Thompson and in most of the Fraser districts.

In the reports, he acknowledged that former commissioner Sproat had done a lot of work there, dividing land into four categories: reserves with permanent boundaries; reserves with indefinite boundaries assigned during colonial times by assistant B.C. land commissioners or Royal Engineers; commonages which were joint grazing lands to be shared with another tribe or with nearby settlers; and temporary reserves, which were those which Sproat had found basically unsuitable. They either lacked adequate water or the land was not useful for agriculture or grazing, but it had been assigned because of being “all that was currently available.”

O’Reilly usually confirmed the boundaries that Sproat had designated for permanent reserves, but he found the other categories difficult to work around, particularly in the Thompson and Fraser canyons. The railway right-of-way often interfered with lands assigned to Indians. As well, sections of the Cariboo Road had collapsed and needed replacing, and other portions needed to be moved to make room for the track. That was unsettling for everyone but frequently devastating for the native residents who could be cut off by a slide caused by the construction, or have their reserve’s boundaries moved again.

As O’Reilly pointed out to Joe Trutch, who was often in Yale and met with him regularly, those Indians had been affected by white men’s activities repeatedly over the past two decades. The gold rush and the building of the wagon road had often intruded into their lands and their fishing areas.

Joe agreed but said the construction had to take precedence over those concerns, whether it was a hindrance to Indians or settlers. “The railway will create permanent change to this land — think how a train passing through a landscape dominates it. And think of the numbers of people and quantities of supplies it can deliver in one fell swoop. Quite a different effect from a stagecoach or pack train.”

O’Reilly thought about Joe’s statement often that winter while he tried to set boundaries for adequate reserves and accommodate the pre-emptors and the railway. His task was quite overwhelming as he understood more about what being the Dominion’s B.C. Indian Reserve Lands commissioner involved. Answering the questions from all the Canadian and British Columbian officials using his reports often became onerous for him.

Excerpted from Peter O’Reilly: The Rise of a Reluctant Immigrant, TouchWood Editions ©2010 Lynne Stonier-Newman