In this classic history of the British naval station at Esquimalt, Barry Gough inventories the remarkable fleet of warships that once frequented our local waters and presents a strong argument for the importance of sea power in the formation of British Columbia. Thetis Island here refers to an islet near the entrance to Esquimalt Harbour.

An observer fortunate enough to be standing on Duntze Head on the east side of the entrance to Esquimalt Harbour on July 25, 1848, would have seen the approach of the first of Her Majesty’s ships to anchor there: the fine frigate Constance, mounting 50 guns, and one of the many men-of-war built in Pembroke Yard, Wales.

On that day, thousands of miles from Portsmouth, she quit the stormy waters of the Pacific by entering Juan de Fuca Strait at Cape Flattery and made her way, as winds, tides and currents would allow, up the 15-mile-wide strait until clear of treacherous Race Rocks islets. Then she came into full view, sails bright against the Olympic mountain ramparts on the far American shore. She then shaped a course so as to run directly into Esquimalt Harbour, taking Fisgard Island to port and Duntze Head to starboard.

All the foretopmen were attentively in their place, ready to loosen sails on command as she swung around into the wind, and at the bosun’s piercing call the canvas was furled, the hull gradually slowed as she came up into the prevailing wind. Almost as if by magic, the clanking of the anchor chain running out and finding its depth echoed round the harbour and through nearby forests, and she came safely to anchor in the snug cove in the southeast corner of Esquimalt Harbour that was to bear the ship’s name.

The Constance was later followed by more than 100 British warships that made Constance Cove their usual haven on the Northwest Coast. Britain had found its anchor of empire in the North Pacific, and from this Canada was to acquire the watchtower on its western shore, with tentacles to the high Arctic and potential influences reaching across the wide Pacific Ocean to Asian shores.

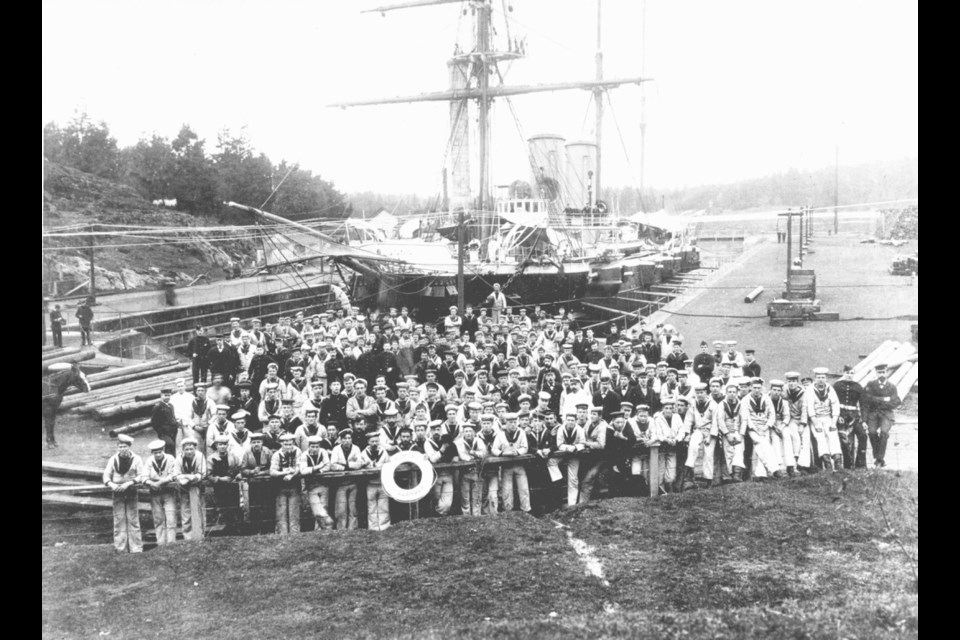

Little by little, the Navy occupied lands to the east and south of Constance Cove. One prize possession was Thetis Island, first used as a refitting spot by the Thetis in 1852, on which crews of shore parties from various ships built primitive sawpits, coal sheds, and blacksmith and carpenter shops. In the course of the speculation in land that accompanied the Fraser River gold rush, James Douglas and John Work, as self-styled “Trustees for the Fur Trade,” sold the island to one Jeremiah Nagle for one pound.

This transaction threatened to rob the Navy of the only land it used in the harbour, and the real-estate grab alarmed Rear-Admiral Bruce, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific. He pointed out that possession was nine-10ths of the law and advised the secretary of the Admiralty that Thetis Island doubtless was naval property by virtue of its occupancy by the Navy for at least 15 years. The struggle for Thetis Island had begun.

In subsequent discussions involving the Admiralty, the Colonial Office and the Hudson’s Bay Company, which owned most of the land around the harbour, the company acknowledged Admiralty title to Thetis Island. This constituted a reservation of land for naval purposes, the first of its kind at Esquimalt, and it conformed to the provisions stipulated in the charter of grant of 1849 by which the company obtained colonizing powers at Vancouver Island. The value of Thetis Island was enhanced in 1860 when the Admiralty approved construction of a depot there to hold 1,300 to 1,400 tons of coal. This project was designed to eliminate the necessity for all ships needing coal to go to the pit-heads at Nanaimo, some 80 miles by sea to the north.

As shipping in Juan de Fuca Strait increased with colonial development, particularly at the time of the Fraser gold rush, many marine tragedies occurred on the south end of Vancouver Island. Already in 1846, Captain Kellett, on survey in the Herald, warned about Race Rocks as “this dangerous group … for the tide makes a perfect race around it.” Many merchant vessels came to grief nearby, with heavy loss of life.

Colonial correspondence contains many accounts that make for melancholy reading. On the recommendation of that famed surveyor Capt. George Henry Richards, who toiled in these seas in the late 1850s and early 1860s and directed what can be said to be one of the most magnificent surveys, the imperial government agreed that two lighthouses needed to be put up as aids to navigation for vessels in the waters of southernmost Vancouver Island and Juan de Fuca Strait. There was urgency to this work, as the toll of ships and lives mounted.

At the narrowing entrance of Esquimalt, on a cluster of rocks called Fisgard Island, contractors and specialists put up a lighthouse in 1860. This lighthouse, visible to mariners for 10 miles in clear weather, was complemented by another built at hazardous Race Rocks Islets. The two lighthouses, which enabled ships to enter Esquimalt by day or night in good weather, are still in use, although nowadays navigating officers employ more sophisticated electronic devices for navigation. Fisgard Island was lit Nov. 16, 1860; Race Rocks, Dec. 26. Here was an imperishable British gift to British Columbia trade and navigation.

Meanwhile, the marine infrastructure of naval supremacy continued to be enlarged. The southern shore of Esquimalt Harbour adjacent to Thetis Island provided several good bays, and auxiliary services were developed on these. This provided the foundation for a small dockyard complex that was constructed later.

At the western extremity of this southern shore was Duntze Head, known locally as “Old Hospital Point,” where hospital huts were erected in 1855 during the Crimean War. These buildings were put in efficient condition in 1858, and their grounds generally were considered as government property. Nearby stood Esquimalt Village, a cluster of ship-chandleries, dwellings, public houses and brothels. To the east lay Signal Hill, its strategic position commanding the rocky peninsula that enclosed Esquimalt Harbour on the south, and along which rough roads led to Victoria on the east.

On the northeastern side of Constance Cove, barracks, which were constructed for the Royal Engineers engaged in the Boundary Commission survey of 1859-1862, were destined to become naval property — simply to keep them from falling into private hands. Farther north on this same shore stood “Dallas Bank,” later known as “Maple Bank,” where the commander-in-chief resided after 1864. In the upper reaches of Esquimalt Harbour lay Cole Island, chosen by naval and military officers as a site for a munitions depot in 1860, one year after the Admiralty decided to establish a powder magazine to supply Her Majesty’s ships in the North Pacific.

Such a facility seemed especially necessary because the international tension between Britain and the United States appeared likely to develop into war. As Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Maitland pointed out to the Admiralty, a powder magazine had to be built as soon as possible, for there was no secure place for ammunition. In case of war, months would pass before a supply could be sent out from England, and ammunition at Valparaiso was not only too far away but was also subject to the vagaries of politics in Chile.

By the end of 1862, the magazine had been constructed on Cole Island, and a marine guard posted day and night to prevent thefts. No longer were powder and shell sent to the storeships at Valparaiso and Callao. The Admiralty decision to erect a munitions depot at Esquimalt Harbour was consistent with its realization that the headquarters of the Pacific squadron would be transferred from Valparaiso to Esquimalt.

Britannia’s Navy on the West Coast of North America, 1812-1914, © Barry Gough. Heritage House Publishing, 2016