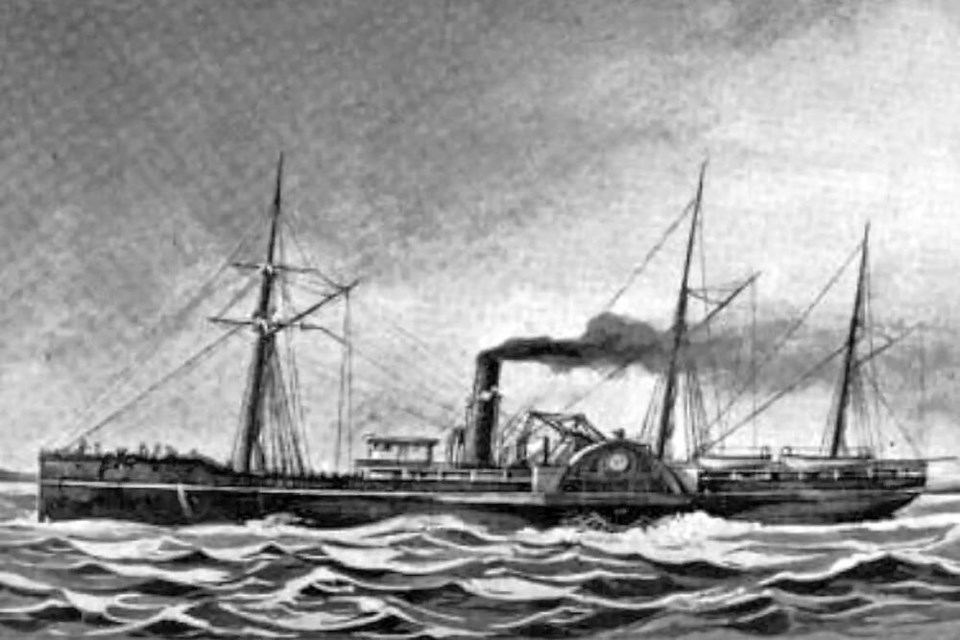

The story of the tragic sinking of the sidewheel steamer Pacific is an enduring maritime drama.

More than 250 people, the famous and unknown, including families, lost their lives after the SS Pacific collided with the clipper ship Orpheus just outside the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the night of Nov. 4, 1875.

It was the worst disaster of its kind at the time. Only two survivors were rescued, one a crew member and the other a member of a Canadian Pacific Railway survey team from Ontario. At least six of his CPR colleagues were not so lucky.

The discovery of the ship’s remains by Rockfish, Inc. was announced last fall, and salvage work by the Northwest Shipwreck Alliance was supposed to begin this year.

My interest in this tragedy was piqued when Rockfish founder Jeff Hummel was quoted in an article in the Times Colonist on Jan. 18 saying that the vessel was carrying all the photographic plates from surveying work by the CPR before it built its cross-Canada rail line. “We will find those plates,” Hummel said.

It’s about 148 years too late for that, because the CPR’s invaluable and delicate glass negatives were recovered a couple of weeks after the sinking, according to reports in the Daily Colonist at the time.

The plates were likely the work of photographer Charles George Horetzky. As far as I know, he was the only photographer employed in an official capacity by the CPR survey in B.C.

Three photo albums documenting Horetzky’s 1875 explorations are preserved by UBC Library, the B.C. Archives at the Royal B.C. Museum and the Vancouver Public Library.

In addition to these albums, Library and Archives Canada has at least 34 Horetzky negatives — out of a possible 59 negatives from his 1875 work — as part of the Topley Studio collection (William Topley was a 19th century photographer based in Ottawa who was noted for his portraiture).

It is believed that Horetzky learned photography at Moose Factory, Ontario, when he was employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company as an accountant.

He was hired by the CPR in 1871 as a photographer, with a secondary role as an explorer. He did not disappoint as far as his photography went, but proved difficult to work with. He was frequently at odds with his employer and his peers.

Horetzky spent nine years with CPR survey groups, and always resented being treated as a photographer — yet at the time he was hired, he was not qualified to be either an explorer or a civil engineer.

Nevertheless, he carried out his assignments with skill, thoroughness and, according to him, austerity.

Horetzky was one of the first Canadian photographers working outside a studio setting who used a new photographic technology: manufactured glass negatives known as dry plates.

No longer were photographers required to bring along chemicals, water and pieces of blank glass in order to create their own negatives through a cumbersome process known as the wet plate.

After Horetzky’s success with dry plate negatives, the Geological Survey of Canada started using the technology.

When the CPR sent Horetzky to B.C., he reported to Marcus Smith, a seasoned railway engineer who had been appointed chief engineer Sandford Fleming’s deputy for the Canadian Pacific Railway surveys, principally in B.C.

During the survey seasons in B.C., typically in the summer months, Smith would inspect the survey parties in the field. He first visited the Homathko River in the summer of 1872 to investigate a possible route to the Cariboo gold fields using Bute Inlet, an idea that had been promoted for a decade by Victoria entrepreneur Alfred Waddington, who thought Bute Inlet offered the fastest route.

Waddington had begun building a road from Bute Inlet through the Homathko River valley a decade before, to connect with the Cariboo district via the Chilcotin Plateau.

Two years later, his effort abruptly ended when most of his road crew were killed by Lhatŝ’aŝʔin (Klatsassin) and several other Tsilhqot’in (Chilcotin) people in late April. Lhatŝ’aŝʔin and five others were hanged in 1864 and 1865, although the federal government exonerated the six men in March 2018.

Horetzky’s first B.C. assignment, two years after Smith’s 1872 trip, was to explore and document with photographs a potential route in the Kitimat region. Two photo albums of that work exist at UBC Library and at Queen’s University.

The following year, Smith ordered Horetzky to Bute Inlet, where the Homathko River provided access through the Cascade Mountains to the central Interior. Smith told Horetzky to visually document a possible route and “to take photographs of the canyons and other views of general interest.”

Horetzky made two trips to the Homathko in 1875.

The most difficult and treacherous portion of the route was through the Great Canyon of the Homathko River, with its sheer rock walls.

In a round trip in June and July, he photographed part of Waddington’s road in the Great Canyon looking upriver.

Horetzky returned to Victoria on July 23. Two weeks later, the Colonist publicized the results of Horetzky’s photographic reconnaissance of the Homathko.

Either he or Smith arranged with local photographer S.A. Spencer to produce mounted prints from the glass negatives obtained by Horetzky.

These prints, along with ones possibly created in October, were sent separately to Ottawa. Their whereabouts are unknown.

While in Victoria, Horetzky took at least one photograph of the city looking west over the Inner Harbour from the top of the Driard Hotel.

Visible under magnification is part of the Victoria Theatre Photographic Gallery on Government Street and signage for its original owner as Vaughan’s Photographic Gallery.

Also visible near the left edge is the Old Victoria Custom House (Malahat Building), which was completed in August 1875.

Almost immediately following his return to Victoria, Smith ordered Horetzky back into the field. Horetzky left Victoria on Aug. 6 aboard the Enterprise, bound for New Westminster, and from there made his way to Soda Creek, on the Fraser River north of what is now Williams Lake.

In September, Horetzky traversed the Homathko River via the south end of Tatlayoko Lake. He documented the impact of flooding in the Great Canyon by showing that Waddington’s road had collapsed.

He returned to Victoria on Oct. 1, and the next day, the Colonist summarized his trip from Soda Creek to the head of Bute Inlet.

Horetzky remained in Victoria for nearly a month, departing for San Francisco on Oct. 30 aboard the sidewheel steamer Dakota. He reached San Francisco on Nov. 3.

On Nov. 13 the Colonist published the first mention of Horetzky’s negatives being lost aboard the SS Pacific. Two weeks later, on Nov. 30, the Colonist also reported the remarkable and unexpected recovery of the Horetzky negatives.

After the SS Pacific sank, various Indigenous communities on both sides of the water boundary between the United States and Canada searched for bodies and cargo. One of those groups, likely Makah people from Neah Bay, found the Wells, Fargo and Company trunk with Horetzky’s negatives.

From the description, it seems the photographs were undamaged by their water immersion. The negatives were shipped to Joseph Boscowitz in Victoria, who presumably forwarded them on to Horetzky in Ottawa.

There are several mysteries around the negatives preserved by the Library and Archives Canada. According to one expert, they are of a size never used by the Topley Studio.

How the Topley Studio obtained the 1875 negatives, along with the negatives from Horetzky’s earlier and later photo surveys on behalf of the CPR, is not known. Horetzky estimated in testimony to a CPR Royal Commission that he had taken about 50 negatives in 1875, perhaps more, but that some were broken in transit.

Most significantly, he never mentioned the negatives being lost and later recovered following the sinking of the SS Pacific. If all the negatives survived the sinking, what happened to those that are not part of the Topley Studio fonds?

Horetzky also testified twice to the CPR Royal Commission that he had deposited the photographs (he never said prints or negatives) with the “Parliamentary Library.” Today’s Library of Parliament, however, has no record of any photographs by Horetzky.

Like many others with an interest in the fate of the SS Pacific and its cargo, I am keen on learning if other glass negatives of the 1875 CPR surveys in B.C. are recovered from the ocean floor.

David Mattison is a former archivist and librarian with the British Columbia Archives, Royal B.C. Museum. He has been researching and publishing about the history of photographers in B.C. and western Canada for more than four decades, and his Camera Workers website is a well-regarded biographical resource.

This article is a condensed version of one published in Photographic Canadiana, vol. 48, no. 4 (January-March 2023).