According to an overwhelming number of studies, way too numerous to mention, reading to preschool children is the single most important activity for building the foundation for the understandings and skills essential for eventual reading fluency.

Those abilities, in turn, are the key to a successful school experience from kindergarten to post-doctorate levels.

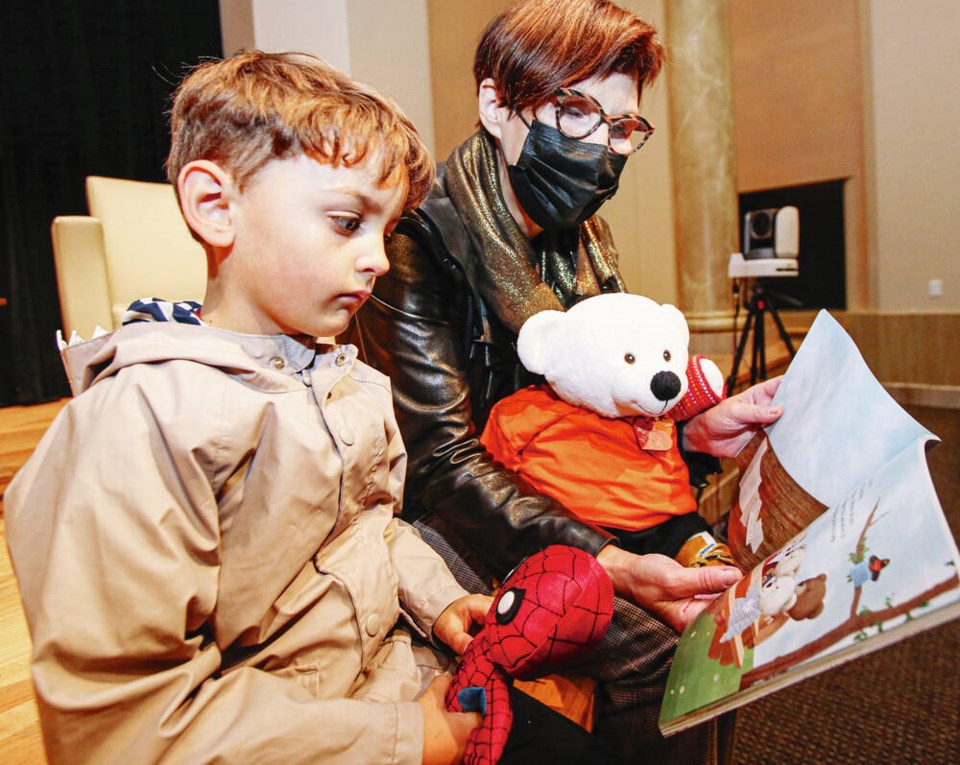

Reading to — and later with — young children every day has been proven to improve cognitive skills and to assist the overall process of cognitive development, the emergence of the ability to think and understand.

Reading to children, especially preschool children, involves the construction of thought processes, including remembering, problem-solving and even decision-making, from childhood through adolescence to adulthood.

Starting in infancy, just listening to a trusted adult read can help with language acquisition, communication skills, social skills and literacy skills, all of which are recognized by child psychologists, pediatricians and early-childhood educators as an essential preparation for success in a school system that relies heavily on the printed word as a path to new knowledge.

Children’s literature has always been one of the best ways to help kids understand the world around them without necessarily having to experience that world for themselves before they are ready. Reading to children helps to expose them to all types of subjects and concepts, while at the same time building an understanding of the complexities of humanity that could not be achieved in any other way.

Children’s books come in a variety of character voices, types of plot and levels of vocabulary, with diverse value systems represented by the characters. The really good children’s books almost always possess certain characteristics. One of those is an interesting story, which is basically what makes younger listeners, and later young readers, invest their time and persistence in a specific book.

It is worth considering that the target audience is composed of children whose vocabulary is generally not that complex yet, so the use of comparatively simple language in a children’s book is a good place to start. Repetitive rhythmic language is also fun (for example, Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? by Bill Martin Jr.).

Most importantly, in order for a book to be considered worthwhile, it should have a message that teaches children some important lessons about life in general. Whether the book is about friendship, family, love, courage or acceptance of others who seem different from the reader, the message of a really good children’s book should be clear, honest and valuable.

The people in the story should seem real, even if the story itself is clearly a fantasy (think Alice in Wonderland or Peter Pan). The characters should be easy for a child to relate to. Some children’s books are even intended, at the level of metaphor, to be read by adults.

Illustrations that are simple, clear and align with the story should expand on and clarify the words in the story. Illustrations are essential — especially if the plot isn’t overly predictable and has clever twists.

Some quick googling by parents or a visit to your local public library or library website will provide information about the best children’s books, sorted by recommended age group. The list will usually include a brief synopsis of the stories and characters.

Learning to read doesn’t just happen. A little more googling will provide further information on the observable features of a child’s stages of learning to read. Those stages range from pre-reading behaviours, where a child “pretends” to read and can retell a story when looking at pages of a book previously read to him or her, right through to reading fluency (being able to read quickly and with understanding).

Later on, the goal is for the reader to develop critical comprehension — relating what a child knows or has experienced to an understanding of new feelings, new attitudes and how to explore issues from one or more perspectives.

As Katherine Patterson — winner of two National Book Awards and a writer best known for children’s novels, including Bridge to Terabithia — explains: “It is not enough to simply teach children to read; we have to give them something worth reading. Something that will stretch their imaginations — something that will help them make sense of their own lives and encourage them to reach out toward people whose lives are quite different from their own.”

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.